Domestication: Labor and Lotus Eating

There exists no stronger representation of gender dynamics and their effect upon the built environment than domestic space. Male architects of the 19th Century

…such as Robert Kerr (1867) set spatial standards of privacy and segregation within the home for the middle-classes in a way that directly paralleled social change in Victorian life…thus middle-class women were very firmly ‘placed’ in the home by many social forces which reinforced one another.[1]

BOYS is speaking to the increased division between “front” and “back” of house, between masculine and feminine, between relaxation and labor in the domestic realm. At the time, the ‘Cult of True Womanhood’ aimed to isolate and domesticate women based upon religious pretenses. With the understanding that the American Republic was founded upon the desire of religious extremists “to worship God in the way they believed to be correct,”[2] it is unsurprising that worship and womanhood were ideologically intertwined as a means of othering and control. True Women, as determined by themselves and their husbands, were expected to be pious, pure, submissive, and domesticated — mothers, daughters, sisters, and wives.[3]

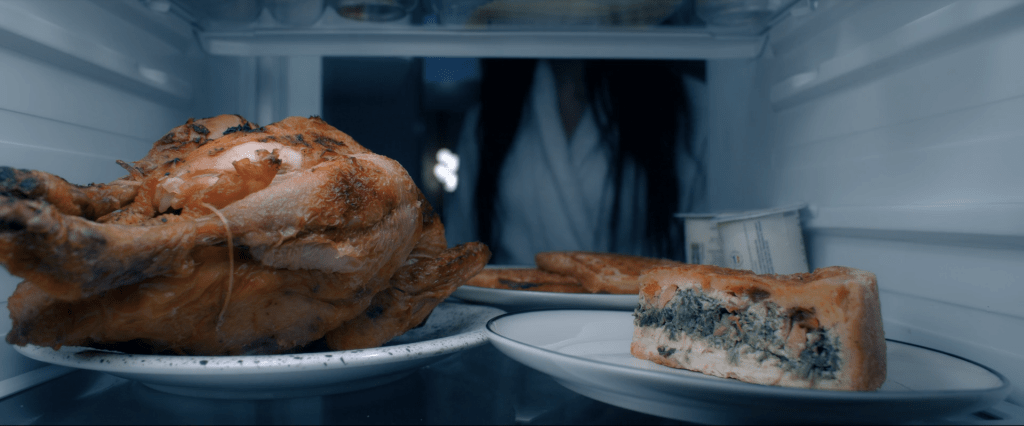

The Cult of True Womanhood demanded that women be mystical angels, a “…better Eve, working in cooperation with the Redeemer, bringing the world back ‘from its revolt and sin.’”[4] This sainthood was primarily mediated by her dedication to family and the home; domestic cleanliness and perfection were equated to religious purity. If her home was tidy and well-maintained, she brought salvation to herself and her family.

Gender-based segregated spatial standards developed by men like Robert Kerr only reinforced the isolation of women because domestic labor and religion could be practiced simultaneously from within the home. Women could care for their children, cook, clean, and commit themselves to a pious life under God from their kitchens: “Unlike participation in other societies or movements, church work would not make her less domestic or submissive, less a True Woman.”[5] Knowledge of and participation in emerging sociopolitical movements such as socialism and suffrage were seen as sin. A well-educated woman was no longer submissive, no longer True. She would have possessed the intellectual tools to liberate herself from her objectification by the systemic patriarchy which ensured her husband’s independence from the home. A socially enlightened woman abandoned the domesticated lifestyle which she was told was the only thing that gave her happiness and worth in both Western society and God’s eyes.[6]

The ideology of The Cult of True Womanhood effectively domesticated, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the process of making someone fond of and good at home life and the tasks that it involves,”[7] feminine bodies for the foreseeable future in its equating of housework, religious salvation, and womanhood. Feminine domestication was maintained further by the architectural and spatial manifestation of True Womanhood. Women occupied kitchens to feed their families, drawing rooms to maintain the company of other women and to sew, bathrooms and dressing rooms to sustain her pure beauty and external appearance, bedrooms to meet her husband’s ‘sexual needs’ or the societal expectation to reproduce or to rest and repeat the cycle of domestic servitude. All other spaces in the home became liminal, rooms that she only passed through to clean or was deliberately kept out of, such as a study, to ensure that she remained submissive and not possessive of the knowledge entitled to men. A woman’s occupation of domestic space was then on defined by her duties as a housewife, a tamed commodity, uncompensated for her labor because it was expected of her.

The religious expectations of The Cult of True Womanhood applied and were disseminated to women of all classes. Feminine domestication was not only reserved for women of the middle class. Wealthy, aristocratic women have also been tamed through means of objectification. Even though economically privileged women, predominantly white women, benefitted from patriarchal systems of slavery under which people of color, predominantly women of color, were hired to relieve the bourgeoisie from domestic labor, they were still bound to the home due to ‘separate spheres’ social and architectural ideology.[8] With their access to capital, wealthy women became lotus eaters, “…a mere shadow of her husband…,”[9] a phantom stuck in the home without a purpose outside of her uterus (especially post-menopause) because of her economic avoidance of domestic labor outside of childbirth. The women of the aristocracy, in their domestication, became almost crystalline, glimmering examples of the luxury accessible via capital, but a commodity nonetheless; they were simply another token of the wealth and privilege their husbands were able to amass under systems of white supremacy and patriarchy.

Not coincidentally, the broadly cited origin of capitalism, the Enclosure Movement, coincides with the advent of the Victorian Era and The Cult of True Womanhood. Ian Angus, in The War Against The Commons, writes that”For almost all of human existence, almost all of us were self-provisioning … For wage-labor to triumph, there had to be large numbers of people for whom self-provisioning was no longer an option…Through force and fraud, common land was privatized.”[10] As public land became privately owned, even more domestic labor was expected of not just women, but marginalized beings, to maintain said property. The drawing of borders to privatize land and the enclosure of women to interior, domestic lives occur parallel to each other during the emergence of the Industrial Revolution, thus fabricating a symbolic fastening between the demarcation of boundaries, property ownership, capital production, and the objectification of women.

Immutably connected to the proliferation of capitalism is the objectification and commodification of the feminine body:

… [Marx] believed that, in time, distinctions based on gender and age would dissipate, and he failed to see the strategic importance, both for capitalist development and for the struggle against it, of the sphere of activities and relations by which our lives and labour power are reproduced, beginning with sexuality, procreation and, first and foremost, women’s unpaid domestic labour.[11]

As Federici outlines, women, in their societal damnation to perpetual unpaid domestic labor, are also exploited as a means of maintaining global capitalism via reproduction—a reality ignored by most until the mid-20th Century during the Second Wave of feminism. Miranda Brady reminds us that “Critical readings of the themes raised during the second wave are as relevant as ever. Continuing to remember them will help us make interventions in contemporary feminist agendas…”[12] especially as women’s rights continue to be stripped away and political rhetoric in the global West becomes more mimetic of antediluvian Christian sensationalism and patriarchal propaganda. The conservation of gendered borders in the home perpetuates the exploitation of women in the domestic realm by maintaining spatial means of othering and objectifying feminine bodies through housework. As long as domestic spaces continue to carry historical connotations of femininity, women will always be commodified by their conceptually programmatic and literally architectural frames.

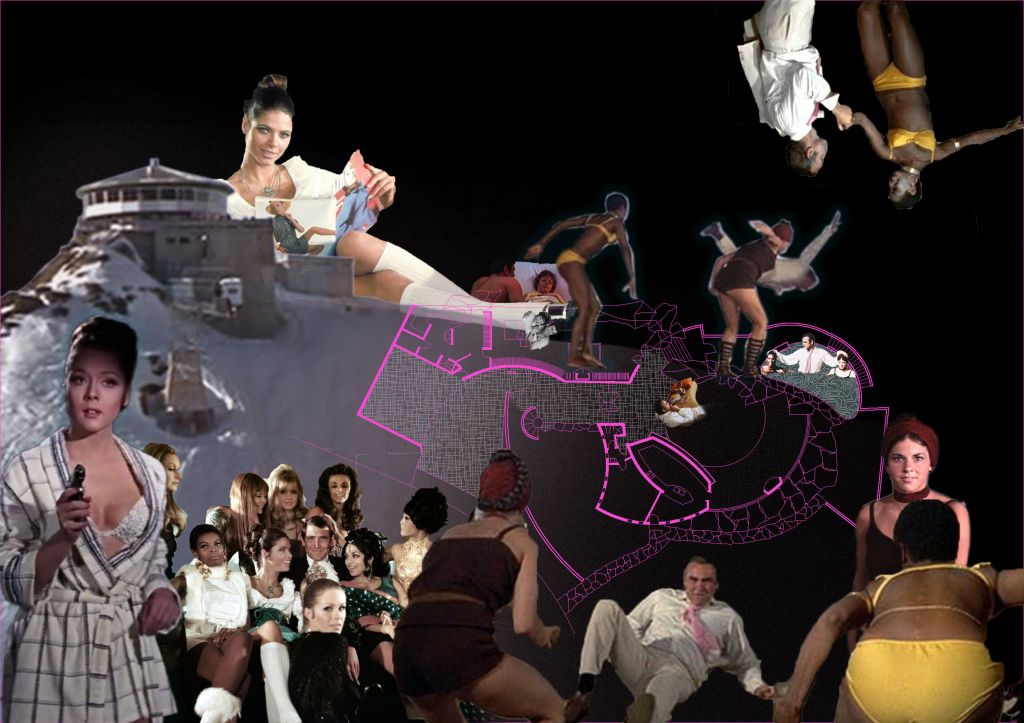

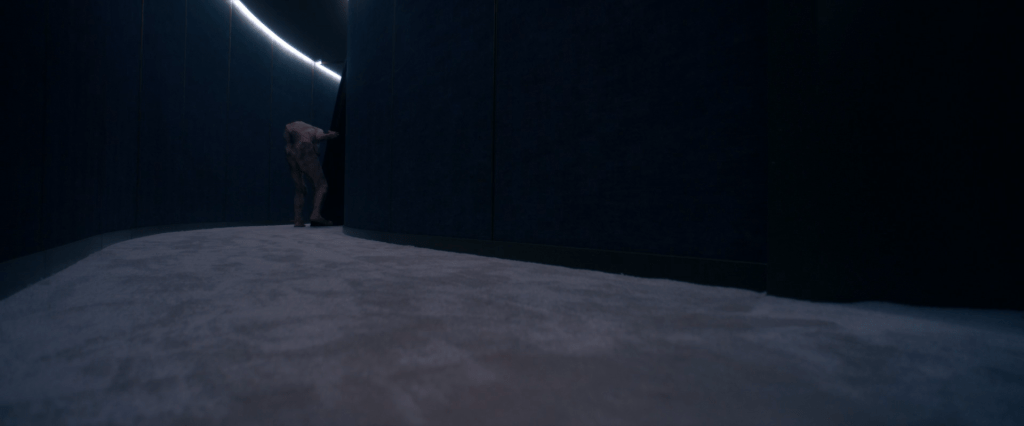

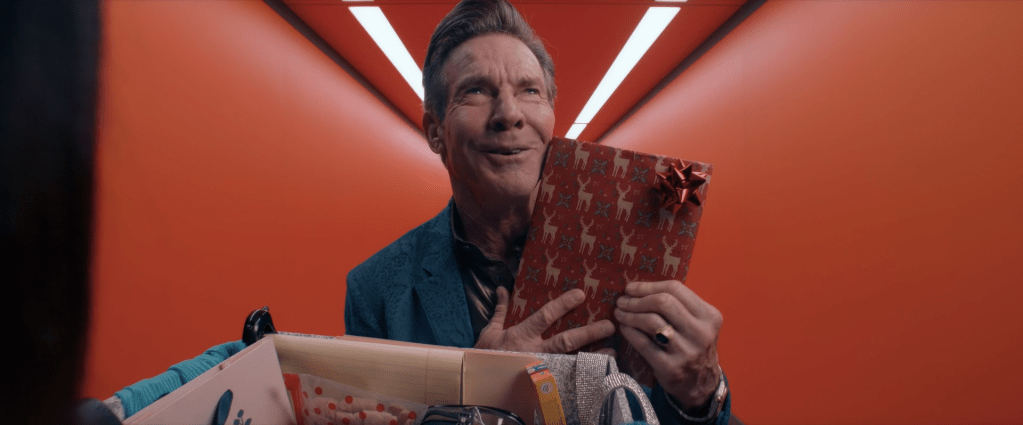

This multi-millennia long history of feminine objectification through architecture can also be observed in contemporary media outputs such as painting, theater, and film. THE DOMESTIC LAIRinvestigates the objectification and confinement of the feminine body through its framing via camera and architecture across five contemporary films. The project aims todefend the symbolic linkage proposed between the objectification of women in the domestic realm, boundary-making, and global systems of capitalism. Otherwise discreet and inconspicuous elements of domestic architecture are hyperbolized and transformed into symbols of the spatial oppression of the feminine body in the architecture of contemporary popular film through the framing of the feminine figure as a confined object in domestic space.

Film, as a broadly consumed form of visual art, continues the traditions and attitudes of European oil painting as outlined by John Berger in Ways of Seeing. He posits that “…men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.”[13] Across not only the history of painting, but also the broader history of the global West, the feminine body has been objectified for men (and women) to observe and act upon and for women to constantly scrutinize. The persistent internal dissection of one’s body in the minds of women has been ingrained into the female psyche through broader cultural outputs and objects such as paintings, or in the context of THE DOMESTIC LAIR,film. This body of research, like oil painting and film, reads the body as the architectural manifestation of our psyches, making the cerebral weight of domestic confinement physical and exponentially more interior.

The project traces formal strategies of framing and traditions of film to the theater and its architectural frame, the proscenium, a built representation of the enclosure, spectacle, and commodification of women in their othering and framing of feminine bodies as distant objects of visual pleasure and entertainment. Film co-opts architectural frames and proscenic spatial techniques to communicate the systemic exploitation of women visually and environmentally. Beatriz Colomina, a pioneer of feminist architectural theory, claims that “Architecture is not simply a platform that accommodates the viewing subject. It is a viewing mechanism that produces the subject. It precedes and frames its occupant.”[14] Architecture will never be free of the frame or proscenium — surfaces and implied boundaries will always produce readings of othering and objectification of the subject they bound — but we as designers can be critical and conscious of what the frames we produce communicate. Rather than taking Colomina’s proclamation as fact, we can reclaim the frame as a means of critique and resistance against systemic oppression instead of its current use as an architectural condition which reinforces patriarchal ideologies. The Domestic Laircontends not only with the framing of the feminine body via borderous, gash-like cuts the skin of the home and their allegorical relationship to capitalism, but also with how cinematic lairs represent the psychological impact of domestic objectification on the feminine body, laborers and lotus eaters alike.

[1] BOYS, “Feminist Analysis of Architecture,” 27.

[2] “America as a Religious Refuge: The Seventeenth Century, Part 1,” Exhibitions, Library of Congress, accessed March 7 2025, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel01.html.

[3] Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 2 (1966): 152. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2711179.

[4] Welter, “True Womanhood,” 152.

[5] Welter, “True Womanhood,” 153.

[6] Welter, “True Womanhood,” 173.

[7] “Domestication,” Oxford English Dictionary, accessed March 7 2025, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/domestication_n?tab=meaning_and_use.

[8] Racial dynamics in domestic spaces will be addressed further as a component of the analysis of Diamonds are Forever.

[9] Miranda J. Brady, “’I Think the Men Are Behind It’: Reproductive Labour and the Horror of Second Wave Feminism,” In Mother Trouble: Mediations of White Maternal Angst after Second Wave Feminism (University of Toronto Press, 2024), 23-4.

[10] Ian Angus, The War against the Commons, (Monthly Review Press, 2023), 9-10.

[11] Silvia Federici, “Capital and Gender,” In Reading “Capital” Today: Marx after 150 Years, edited by

Ingo Schmidt and Carlo Fanelli (Pluto Press, 2017), 80.

[12] Miranda J. Brady, “A Long Way from Liberation,” In Mother Trouble: Mediations of White Maternal Angst after Second Wave Feminism (University of Toronto Press, 2024), 100.

[13] John Berger, “Chapter 3,” In Ways of Seeing (1972.)

[14] Beatriz Colomina, “The Split Wall,” 83.