Waters, Mark, dir. “Mean Girls.” 2004.

FILM SUMMARY

Cady Heron, 16 years old, has been homeschooled until her junior year of high school. Her and her family have recently moved back to Evanston, Illinois, an affluent suburb of Chicago, after living in Africa for the past twelve years. Mean Girls follows Cady through her first year at North Shore High School as she encounters American teenage girlhood and social cliques for the first time. Cady struggles to make friends on her first day but ultimately meets and befriends Janis and Damian, two other outcasts who outline North Shore’s ecosystem of popularity to Cady. They warn her to steer clear of ‘The Plastics,’ led by Regina George, a callous queen bee who rules over the dynamics of the school.

Regina unexpectedly invites Cady to join her and the other ‘Plastics’, Karen Smith and Gretchen Wieners. Despite her initial apprehension, Janis and Damian encourage Cady to remain friends with the group to gain intel on the inner workings of Regina and her friends, especially because Janis claims that Regina “…ruined [her] life;” Cady agrees. During her calculus class, Cady meets Aaron Samuels and is immediately infatuated with him. She confesses her new crush to Gretchen at lunch the next day and is advised to stay away from Aaron because he is Regina’s ex-boyfriend; Regina learns about Cady’s crush and tells her that she no longer cares about Aaron and that Cady is free to pursue him.

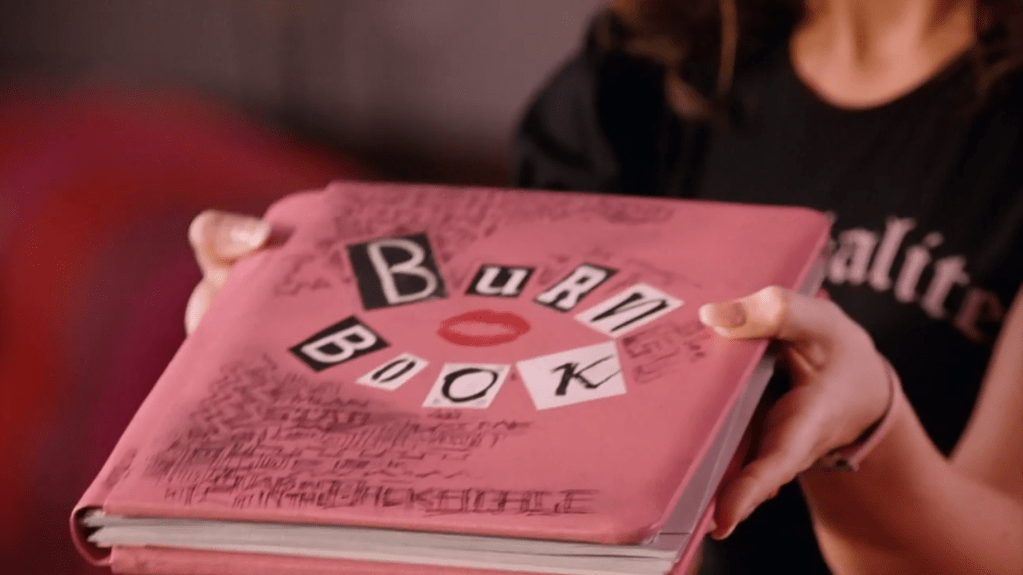

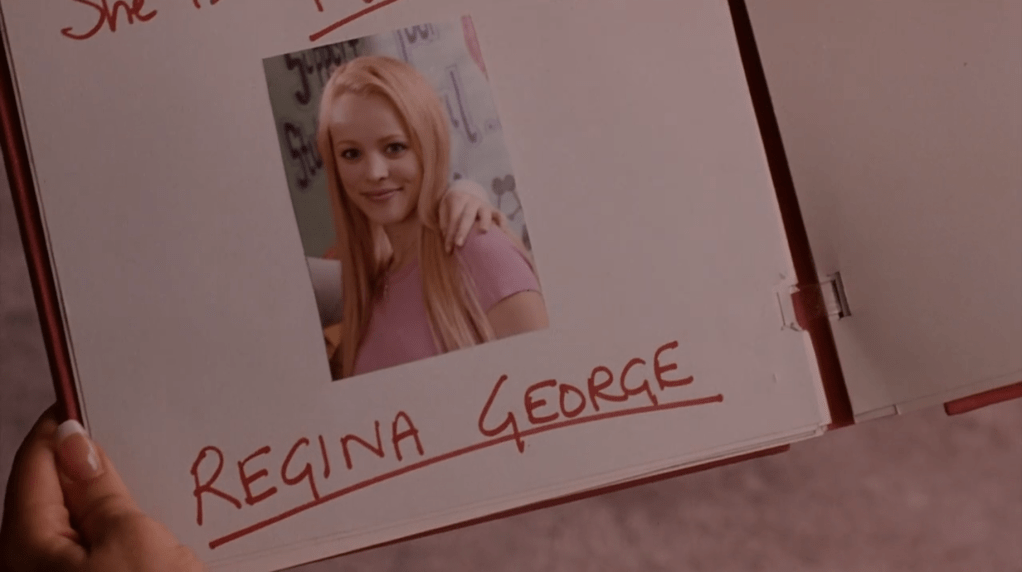

After a visit to the mall, The Plastics indoctrinate Cady by showing her their ‘Burn Book,’ a diary-esque journal in which they write scathing critiques of their classmates and teachers. As she grows closer to The Plastics, she is invited to join them at a Halloween party. Regina offers to talk to Aaron on Cady’s behalf at the party but instead kisses him and rekindles their romance. Cady, feeling betrayed, decides to sabotage Regina with the help of Janis and Damian.

Cady learns from the social manipulation techniques of The Plastics and uses them to create conflict amongst the other girls in her favor. Gretchen reveals that Regina has been cheating on Aaron, allowing Cady to break up their relationship so that she can pursue him herself. She also preys on Regina’s own insecurities about her already thin figure and gives her Kalteen bars, a high-calorie protein bar from Sweden, under the guise that they are weight-loss inducing. As Regina begins to gain weight and become distraught over her body image, she wears sweatpants to school, breaking the dress code she set for The Plastics. Regina is excommunicated from the clique, leaving Cady as the leader of the two other girls.

Cady hosts a party while her parents are out of town at which she admits that she’s been lying to him about needing calculus tutoring in order to spend more time with him. Aaron delivers a sharp wake-up call to Cady, she has become no different from Regina, manipulating everyone around her to get her way. Janis and Damian ridicule Cady for throwing a party instead of going to Janis’ art show, endorsing Aaron’s claims that she has become ‘plastic’ herself.

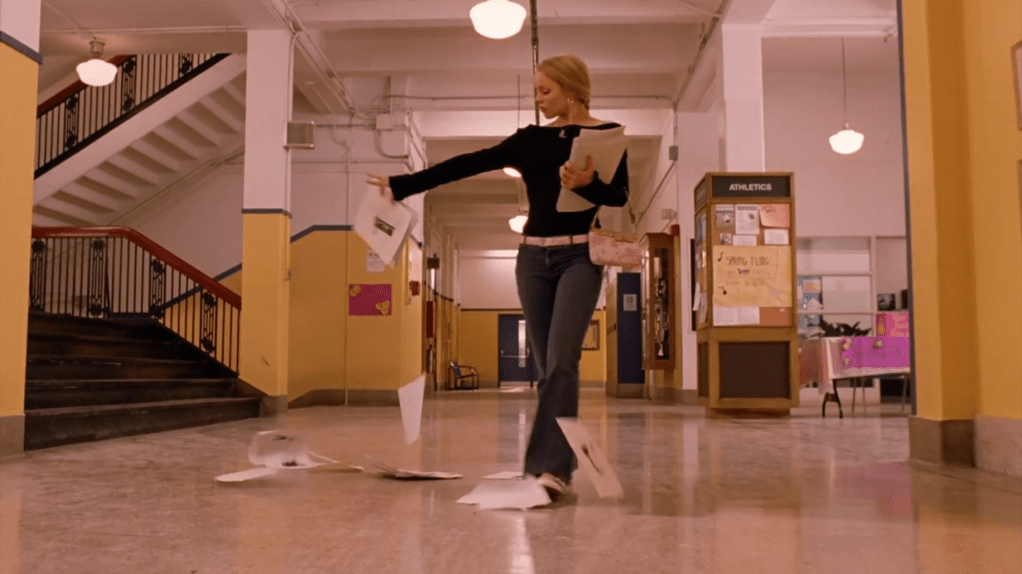

Regina discovers that Cady has been sabotaging her and devises a plot to pin the writing of the Burn Book onto Cady. Regina litters images of the book’s contents through the halls of North Shore High School, instigating fights amongst the student body. The junior girls are gathered into the school’s gymnasium and encouraged to either take responsibility for writing the Burn Book or discuss the toxic social dynamics between themselves. Janis confesses to plotting against Regina to the other female students’ chagrin, making Regina flee. Cady follows her, attempting to apologize, but is interrupted as Regina is struck by a bus in front of the school.

Cady takes responsibility for writing the entirety of the Burn Book, becoming an outcast again. After purposely failing calculus to spend time with Aaron, Cady joins the Mathletes to earn extra credit to remedy her grade. She leads the team to winning the state championship and they attend the Spring Fling, a school dance, together. At the dance, Cady is crowned Spring Fling despite the turmoil she instigated. She atones for her past actions and breaks the crown she is given, emphasizing that its “just plastic” and amends her relationship with Aaron. Regina and the other Plastics find peace through ridding themselves of spiteful clique dynamics by finding friends and other outlets that allow them to be themselves.

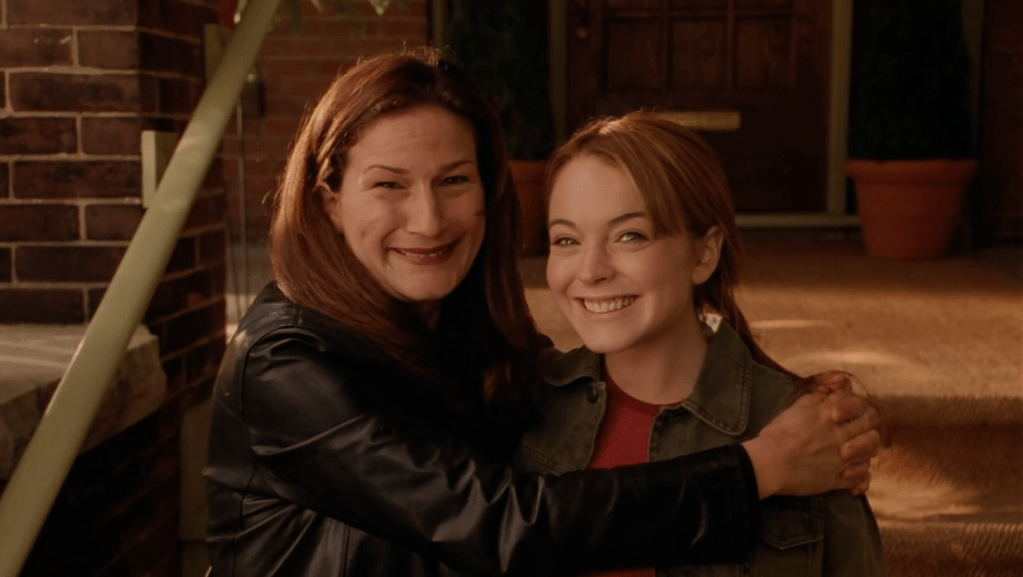

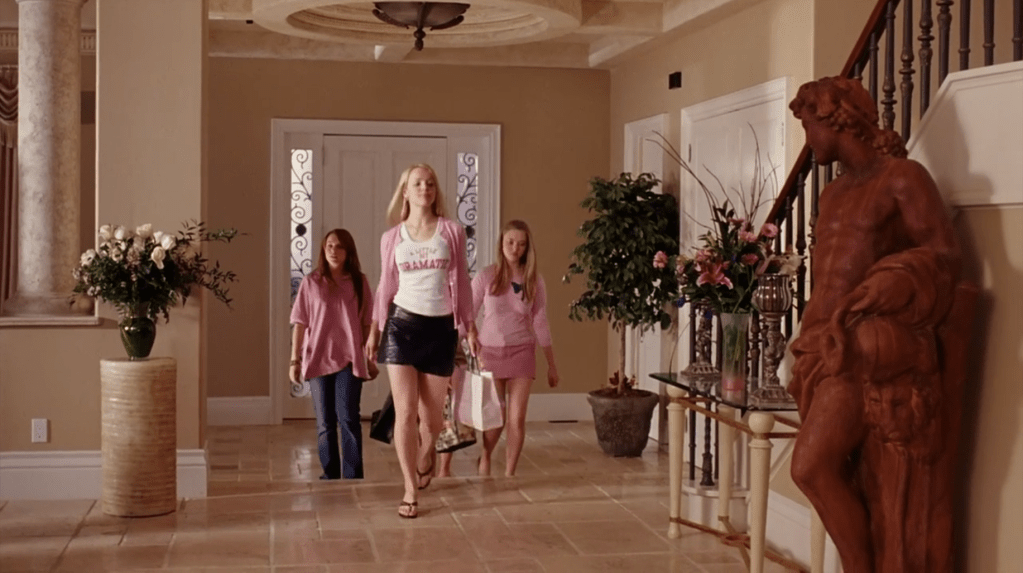

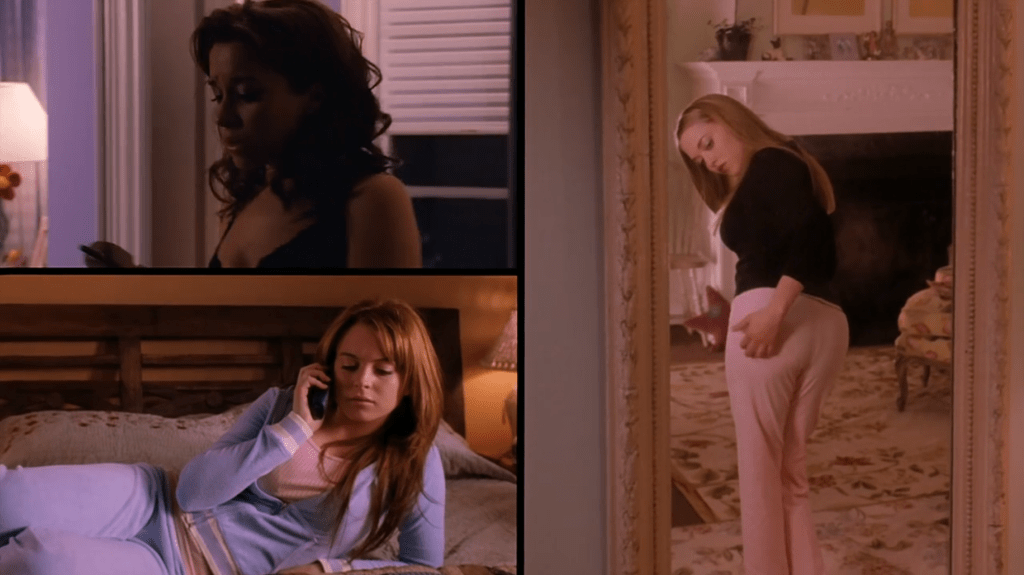

Regina George is objectified and sexualized by the frame produced by the silhouette of her mother’s body and the doorway into her bathroom as she gets ready for the Halloween party in Mean Girls, architecturally representing her restriction to a role of complacency within patriarchy as a white woman who benefits from the oppression of others. Regina’s mother, similar to Bambi and Thumper in Diamonds are Forever, is objectified past interpretation as human, she is simply a figure that further frames Regina within the center of the camera’s view. Mrs. George is also complacent within systemic patriarchy; she benefits from the preferential treatment of white women and the expectation that they be domesticated stay-at-home mothers while their masters (husbands) earn a wage to support their households. Mrs. George is no more than a house bunny, a means of sexually reproducing the next generation, Regina and her younger sister, to perpetuate white male hegemony over their suburban domain.

Mrs. George pushes Regina to sexualize herself in her adolescence, encouraging her to have sex with her boyfriend and to dress as a Playboy bunny for Halloween. The framing of Regina between her mother’s body and the architecture of her bedroom, uncoincidentally the master bedroom of the George’s mansion, represents her constraining between maternal influence, adolescent innocence, and patriarchal master ideology.

In western cultural spheres, women are either angelic Madonnas or whores, there exists no morally ambiguous space for women to occupy with no external scrutiny. Mrs. George’s framing of Regina precariously thrusts her adolescent daughter towards sluttiness; she wants her daughter to be attractive because she knows that in her sexualization and objectification, Regina holds power over her social circle because she is more appealing to men and reaps more benefits from misogynistic, patriarchal ideology. Mrs. George’s raising and framing of her daughter juxtaposes the traditional domestic education of young women. In England and the United States, many teenage girls were enrolled in ‘home science’ courses at schools and universities, studying “…cookery, laundry work, needlework, housewifery, applied science, hygiene, economics and ‘home problems.’”[1] These educational opportunities were designed for young women who were destined for housework, preparing them for the domesticated, interior lives men expected from them as ‘pure’ women, ‘angels in the home.’ The objectification of Regina’s body via framing by her mother exemplifies the 21st Century iteration of home science training for the upper class. Instead of teaching Regina how to cook and clean, her mother teaches her how to pose and present herself as an object of male desire because their economic privilege liberates them from all conventional domestic labor tasks. Now, their housework becomes solely sexual, their role is to reproduce the next generation; in teaching Regina how to seduce, her mother prepares her for contemporary life as a housewife where her value is directly tied to her youth, attractiveness, and child-bearing abilities. The compression of Regina’s body within the frame of the camera as a result of her mother’s body makes this generational adherence to patriarchal dogma spatial. Regina George is physically objectified in the space that equates her to a patriarchal master and by the most important feminine influence in her life, her mother.

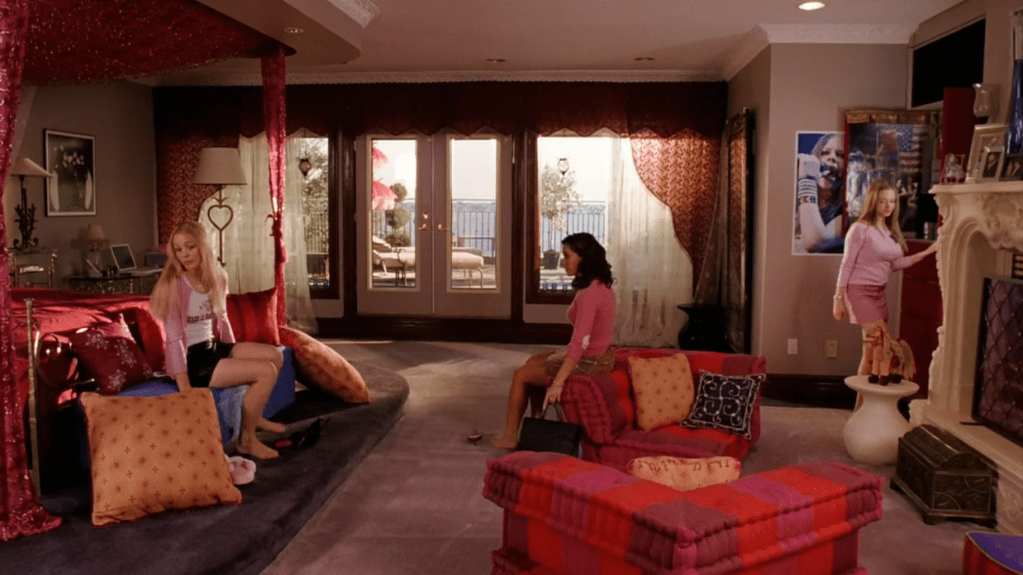

Regina, in her occupation of the master suite, adopts the role of patriarch in the household, reigning over her parents and friends from the most powerful space in the home. Throughout the film, Regina exploits her friends into believing that the men around them are the sources of their anguish, when in reality she is the one orchestrating the social conflict between all of the main characters through her writing of the “Burn Book.” In doing so, Regina attempts to absolve herself of all responsibility of the misogyny-laden diary she creates, blaming its ideological content on women of color and men. bell hooks highlights this repudiation responsibility as common amongst white women in the real world when confronted with issues of sexism, racism, and classism:

Male supremacist ideology encourages women to believe we are valueless and obtain value only by relating to or bonding with men. We are taught that our relationships with one another diminish rather than enrich our experience. We are taught that women are ‘natural’ enemies, that solidarity will never exist between us because we cannot, should not, and do not bond with one another.[2]

Rather than recognizing the privilege afforded to them by association with white men, white women would rather play the role of victim, ignoring their role in the oppression of women of color through their complacency and comfort under patriarchy, claiming that the power men hold over them is still oppressive despite the fact that women of color are demonized and dehumanized while white women are still mortal in the eyes of men.

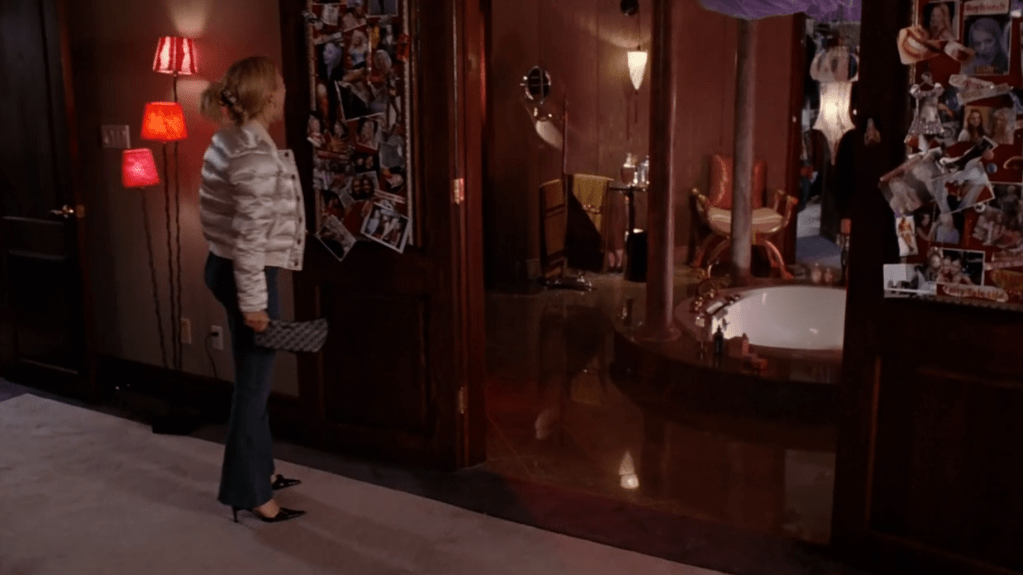

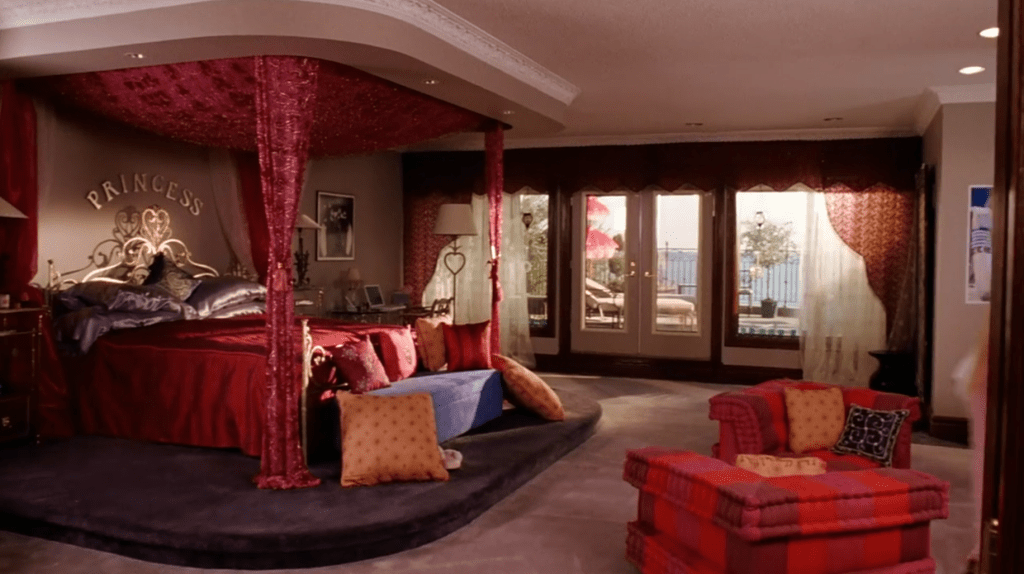

The interior fashioning of Regina’s bathroom also frames her as a product and commodity of patriarchal ideology and wealth. Regina is framed by an opulent, marble bathtub fitted out with decorative ionic columns, reminiscent of interiors of 18th Century France. At that time, French interiors “…[were] an apparatus that produced performances of sociability in accordance with culturally specific ideals of cultivated behavior. It was… an arena for a complex and paradoxical enterprise that… became a key means of defining elite cultural reality.”[3] Furniture at the time was used as a means of defining appropriate social behaviors in the home, encouraging lounging, indolence, and egocentrism in the upper classes by creating spaces tailored to personal comfort, pampering, and opulence; Regina’s bedroom and bathroom are no different. The luxury which surrounds Regina’s body in the selected still all serves the purpose of the cleansing of her body and her physical appearance. Maintaining her attractive, young appearance is another way in which she makes herself appealing to men, and as long as she is an object of male desire, she will hold power over the other beings in her life.

In sum, the perfected central framing of Regina’s body as she gets ready for the Halloween party suspends her within a web of conflicting patriarchal dictations of acceptable feminine behavior. Historically, women were expected to be docile, domesticated, flawless housewives ever dedicated to their husband’s comfort and pleasure. Contemporarily, wealthy women like Regina and her mother have increasingly faced domestic objectification and sexualization as capital relieves them of domestic labor. Regina, then, is first framed between maintaining her youth and becoming a hyper-sexual vision of patriarchal desire. Additionally, Regina’s occupation of and compression within the master bedroom of her family’s home spatializes her adoption of a ‘master’ mentality. She has become the most powerful person in her household because of the space she lives in and exerts her authoritarian, patriarchal, master privilege over not only her family, but also her friends as she manipulates them to achieve all of her desires and total hegemony over all of her social circles throughout the film.

[1] Ann Oakley, “Teaching Girls about Housework.” In The Science of Housework: The Home and Public Health, 1880-1940, 1st ed., (Bristol University Press, 2024), 32.

[2] bell hooks, Political Solidarity between Women (1984), 293.

[3] Mimi Hellman. “Furniture, Sociability, and the Work of Leisure in Eighteenth-Century France.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 32, no. 4 (1999): 437-8, JSTOR.

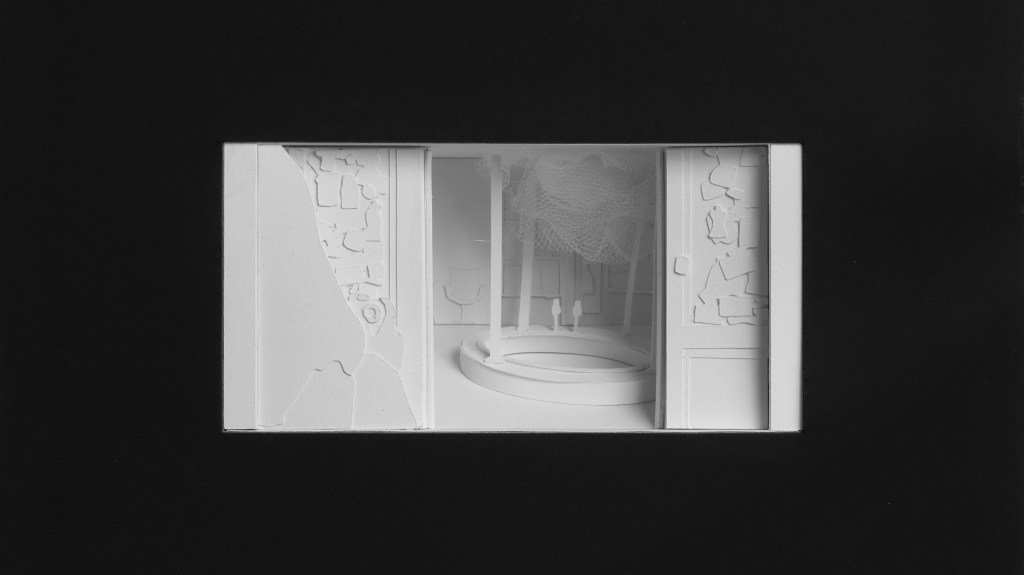

Stills