Joon-ho, Bong, dir. “Parasite.” 2019.

FILM SUMMARY

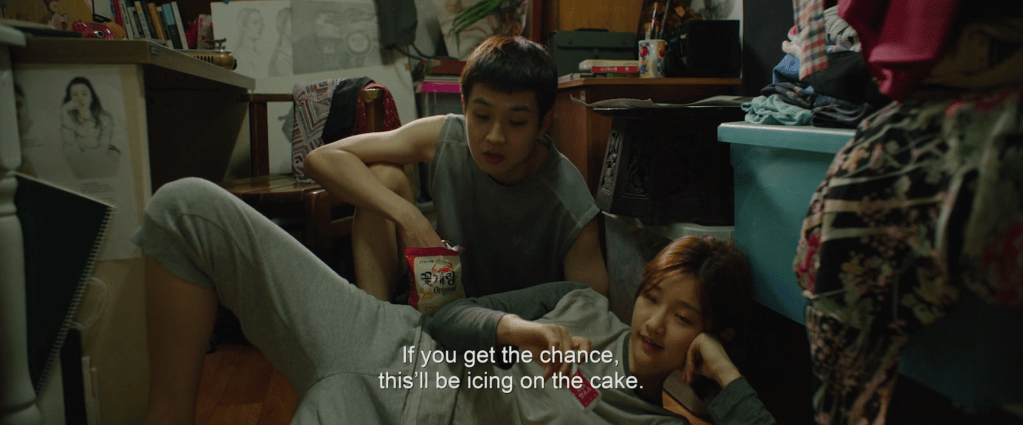

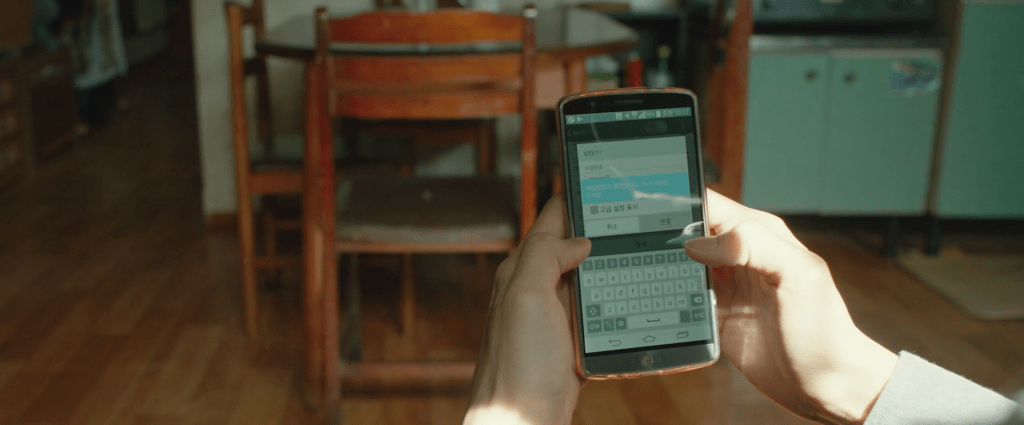

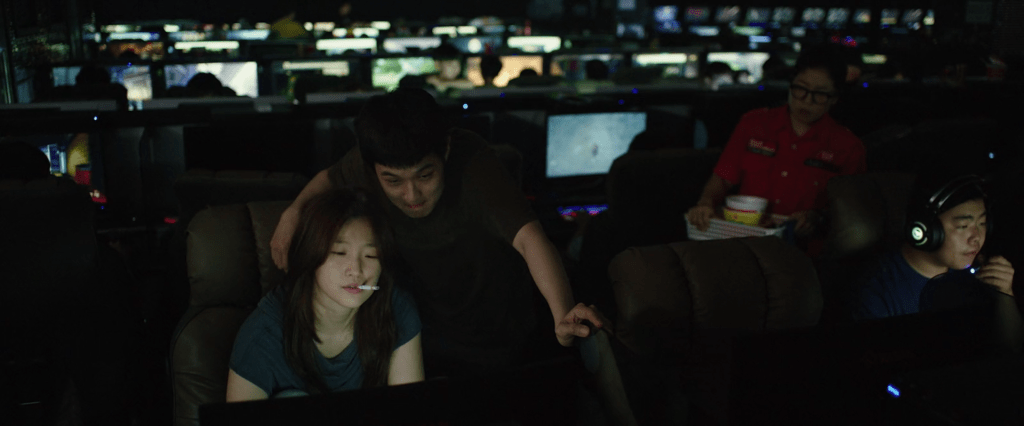

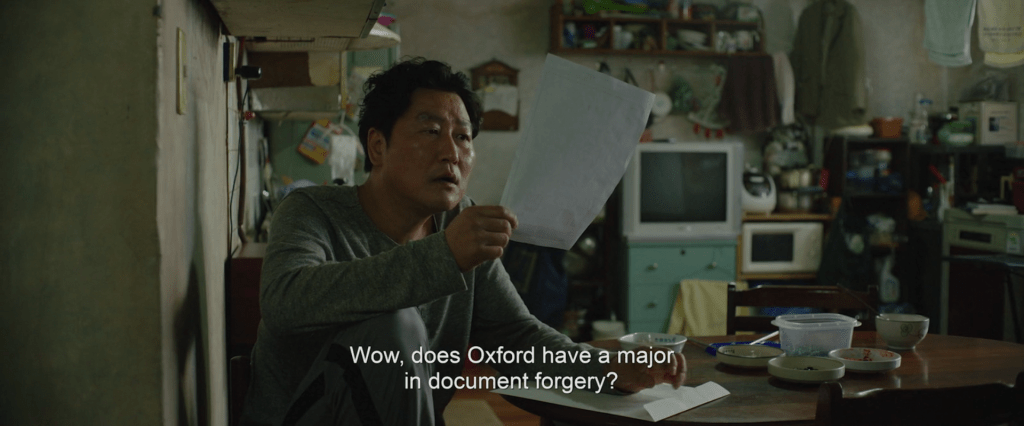

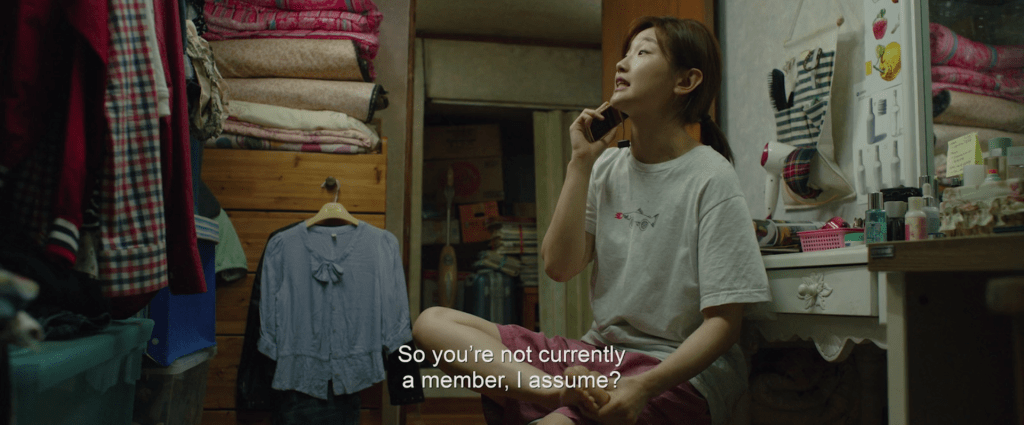

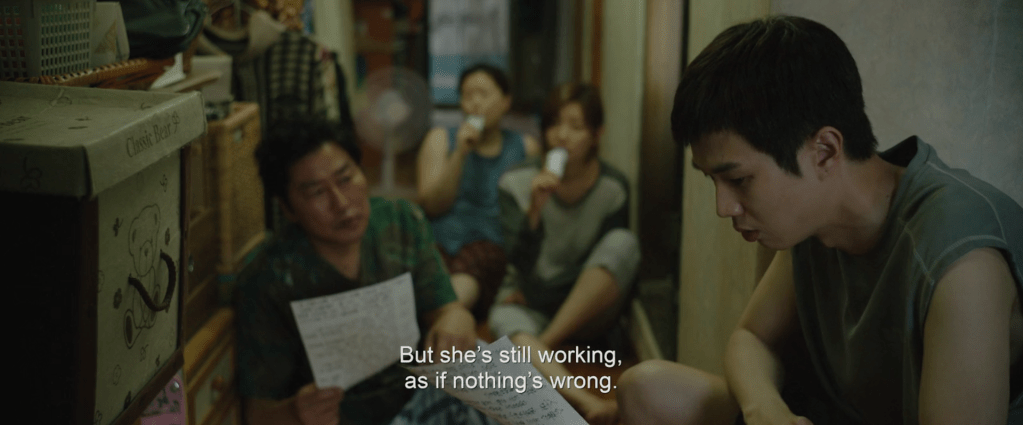

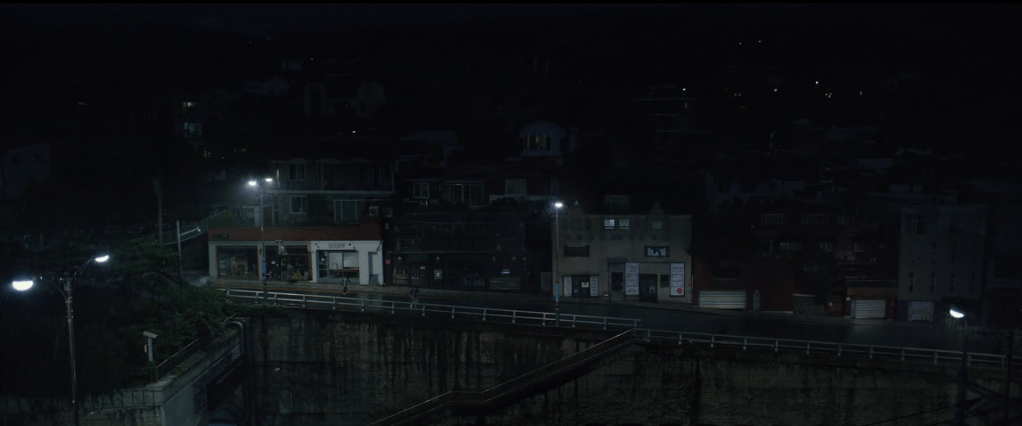

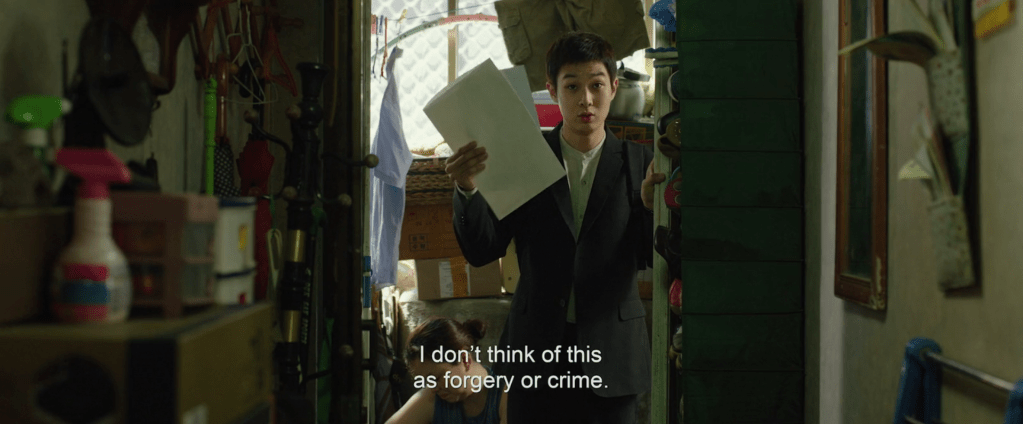

Parasite revolves around two families from Seoul, South Korea—the Kims and the Parks—and their reciprocal parasitic relationship. The Kim Family hails from Aheyon-dong, an impoverished and densely populated neighborhood in Seoul; they live in a banjiha, a semi-basement apartment that is a common housing typology in the area. As the Kims face job insecurity, the son of the Kim family, Ki-woo, is encouraged by his friend Min to take over his job as an English tutor for the daughter of the wealthy Park family by falsifying his educational records. Ki-woo, with the help of his sister Ki-jung, forges a transcript from the prestigious Yonsei University and secures the job.

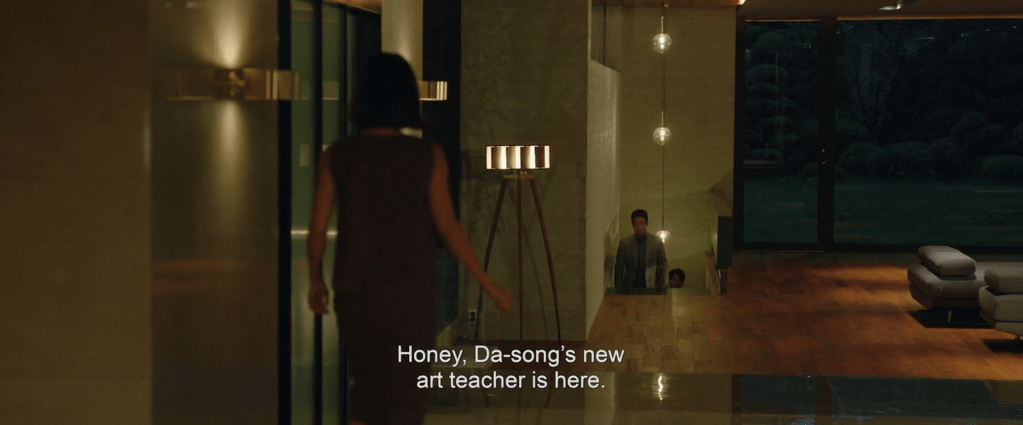

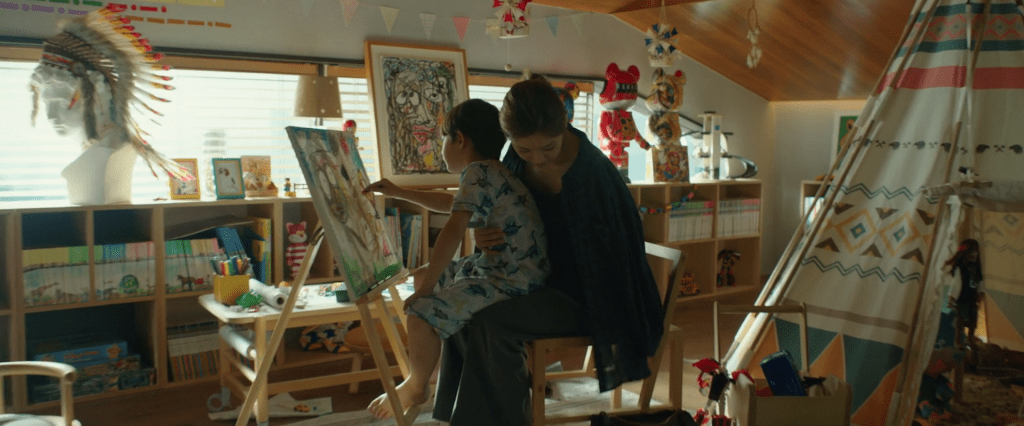

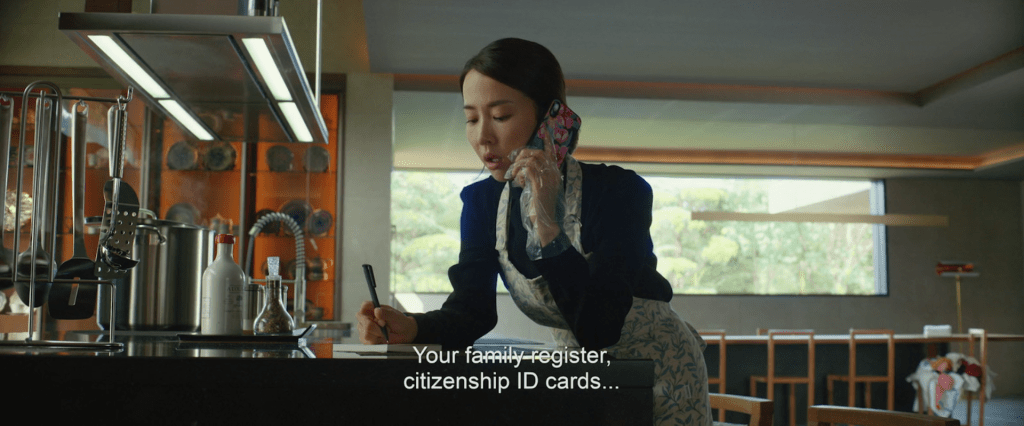

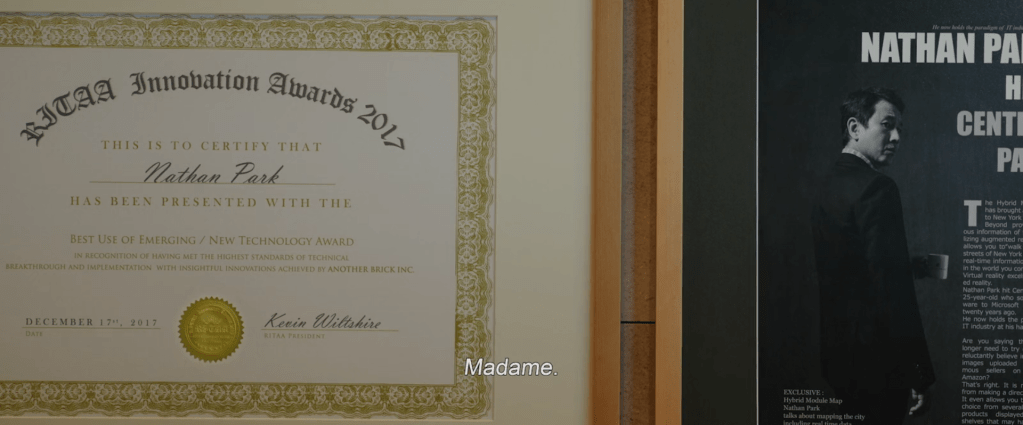

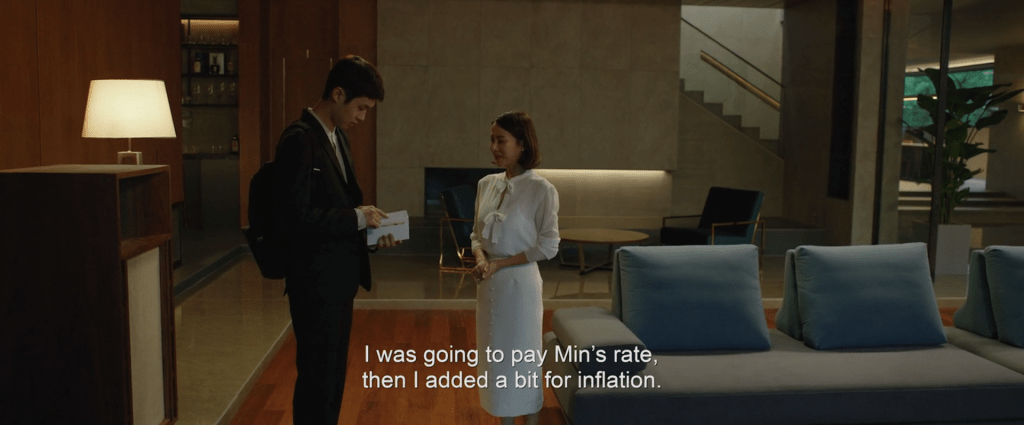

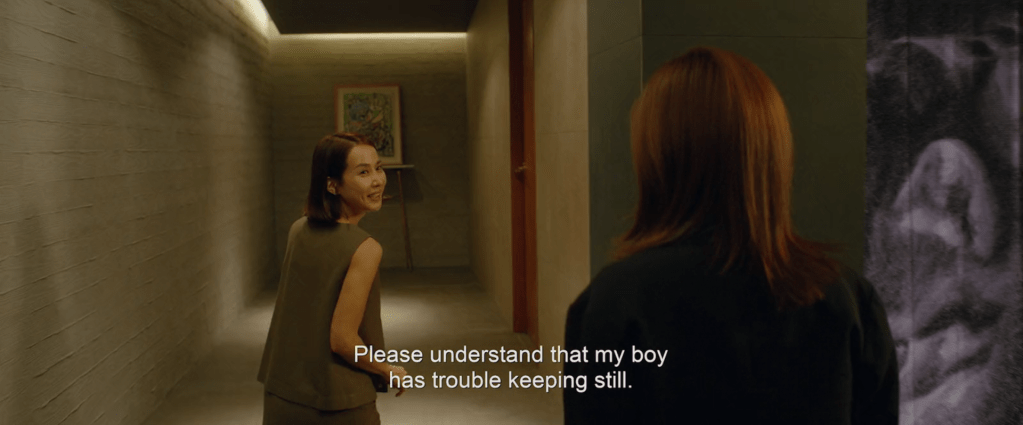

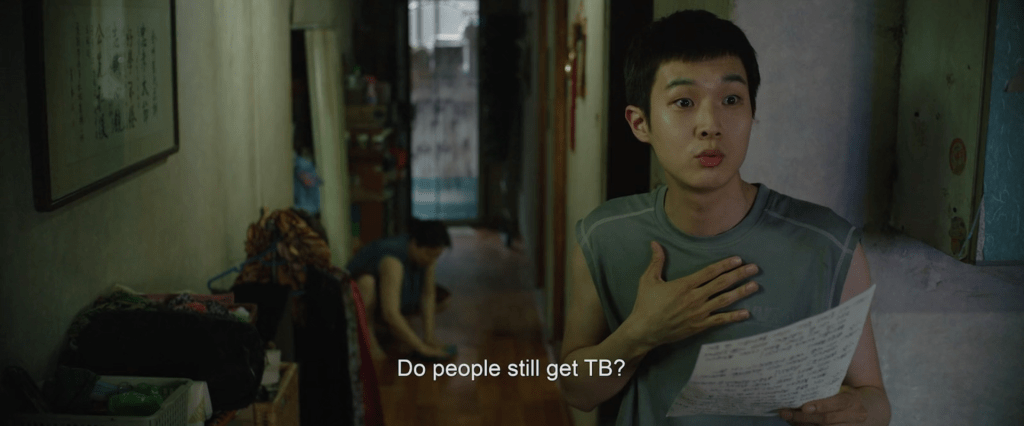

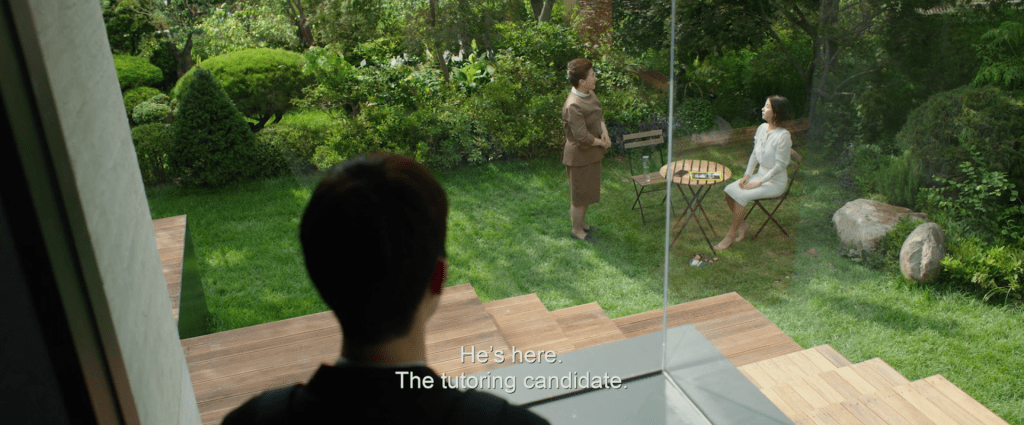

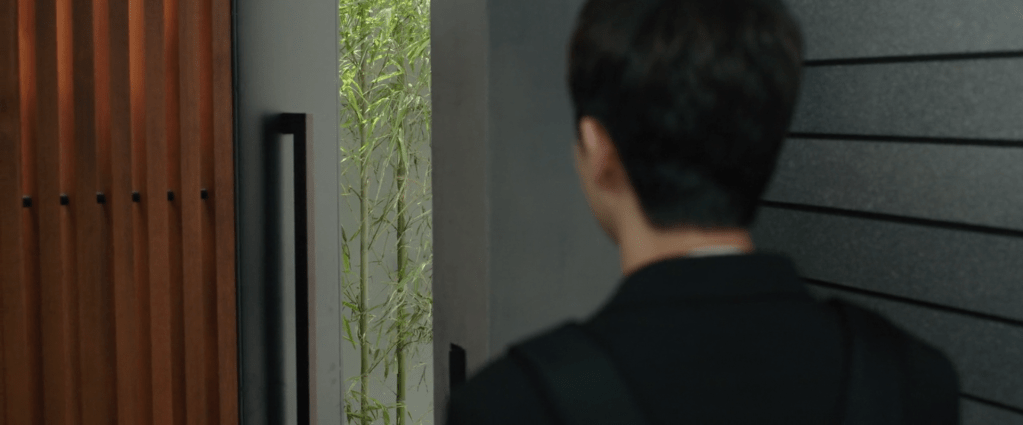

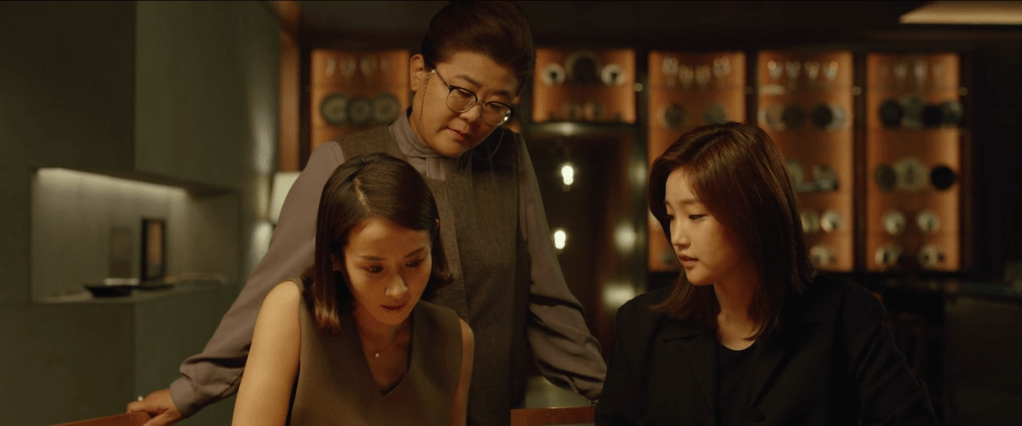

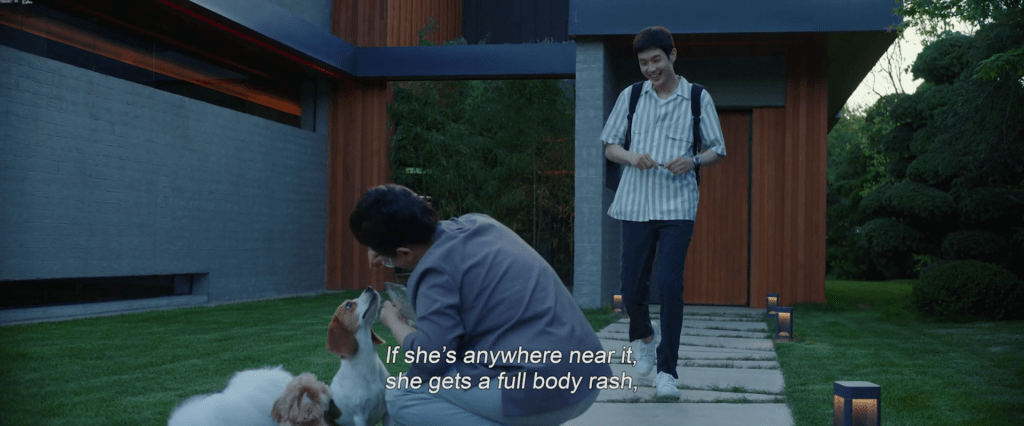

The Park Family lives in Seongbuk-dong, an incredibly wealthy neighborhood in Seoul. When Ki-woo visits the Parks for his job interview, he learns of the naivety of Park Yeon-gyo, the mother of the family, and devises a plan to find jobs for all of his family members as domestic servants of the Parks. Ki-jung is hired as an ‘art therapist’ for the Parks’ son Da-song, who has been traumatized after seeing a ‘ghost’ in the kitchen on his birthday the year prior. Ki-woo and Ki-jung work in tandem to frame Mr. Park’s driver as a pervert and Moon-gwang, the Parks’ housekeeper, as secretly suffering from tuberculosis to open new positions for their parents to find employment within the Parks’ home. In this moment, the Kims and the Parks are both parasites; the Kims secretly invading the home of and relying on the Parks for financial stability and the Parks leeching off the domestic labor provided by the Kims to account for their own inability to take care of themselves.

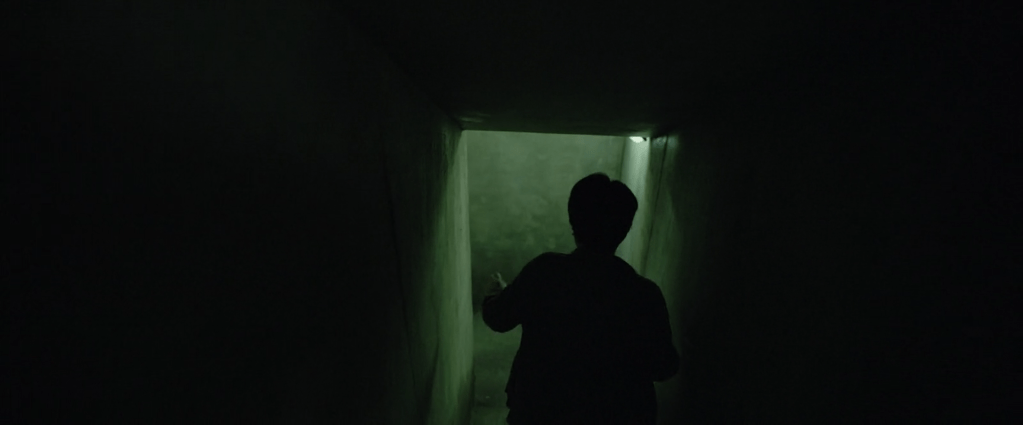

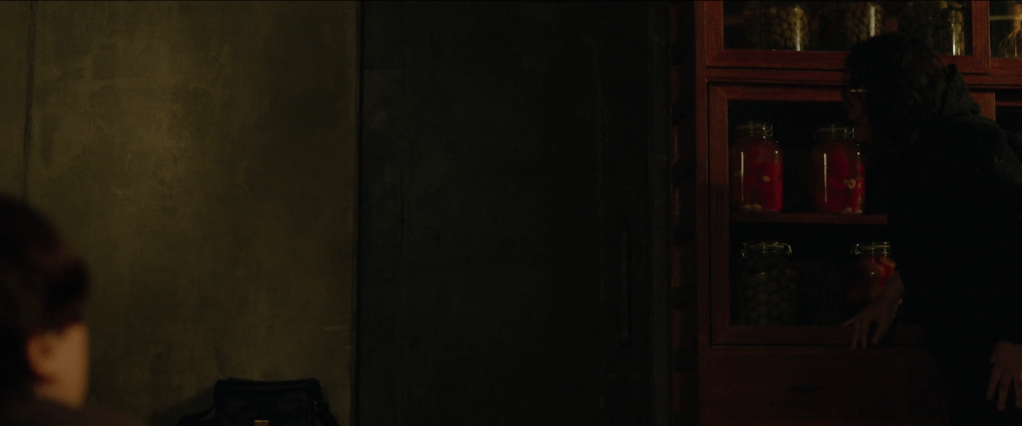

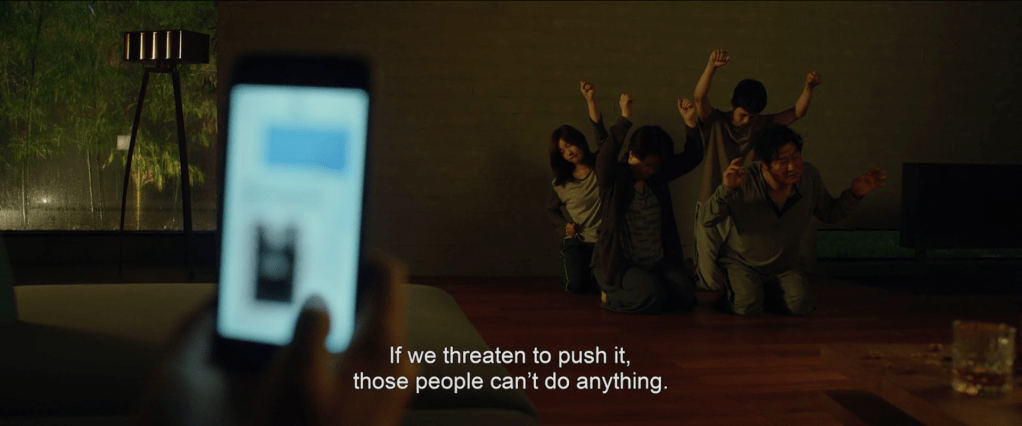

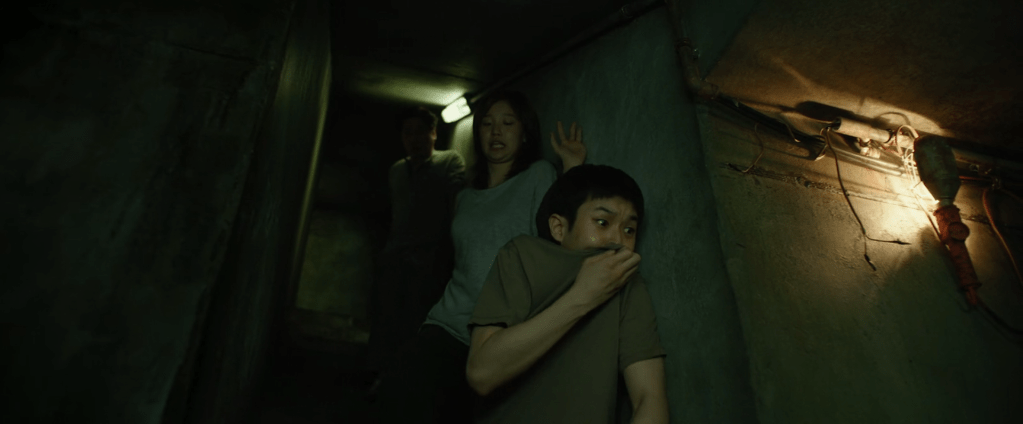

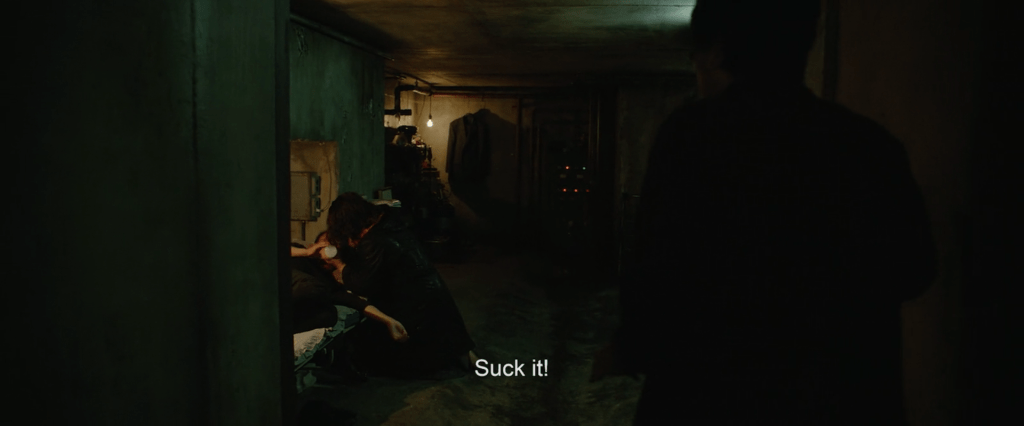

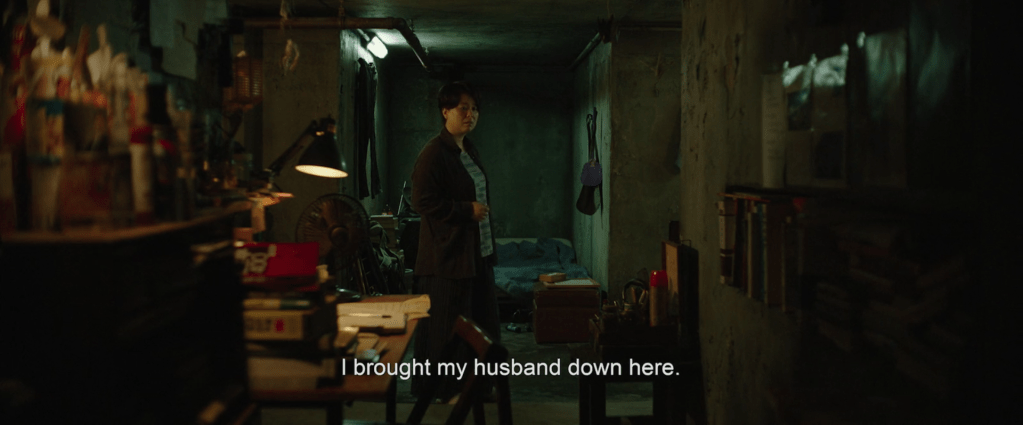

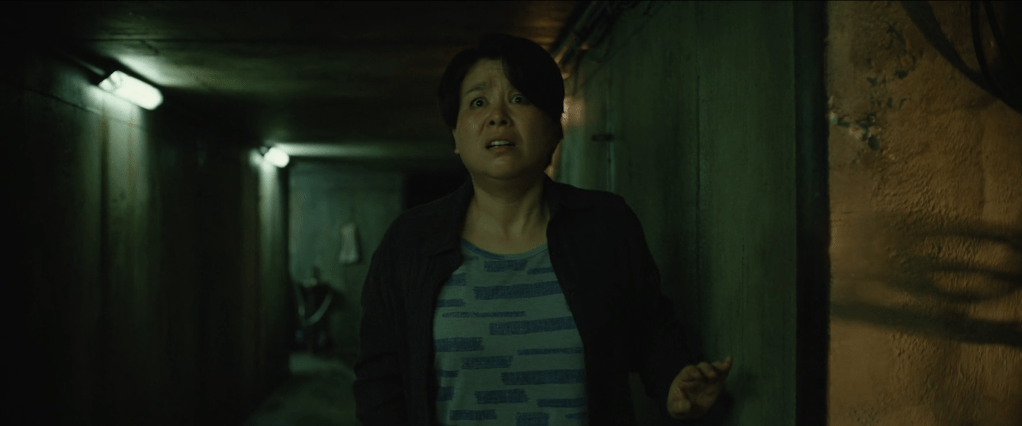

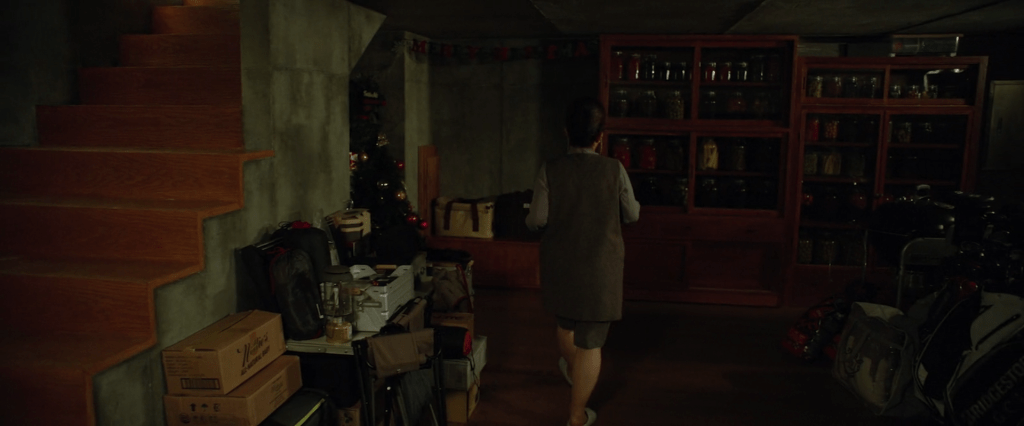

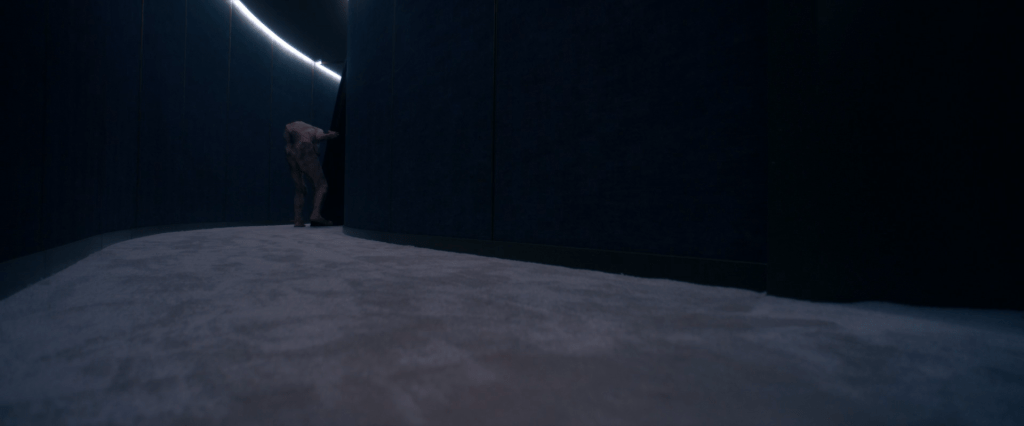

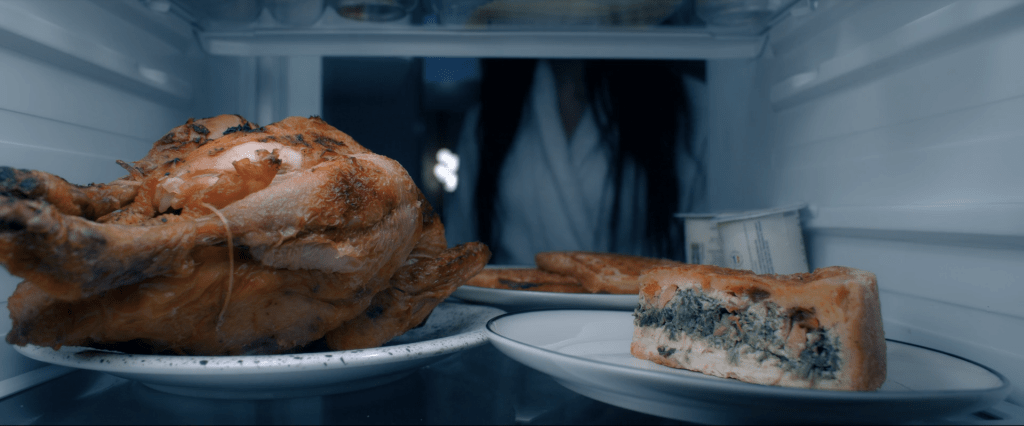

The Kim Family captures a glimpse of the posh lifestyles of the Parks’ while the family is away on a camping trip for Da-song’s birthday, enjoying the lavish amenities their employers are accustomed to. The Kims’ weekend of opulent relaxation is interrupted when Moon-gwang unexpectedly visits the Parks’ mansion claiming to have forgotten something in the basement. Moon-gwang immediately runs to the basement pantry to reveal the entrance to a secret bunker built by the architect and former owner of the home. Her husband, Geun-sae has been living in the bunker for the duration of Moon-gwang’s employment to the Park Family to hide from debt collectors; he was the ‘ghost’ seen by Da-song, leaving the bunker to steal food from the upper areas of the house. Moon-gwang tries to make a deal with Chung-sook to allow her husband to stay in the bunker, but the rest of the Kim Family tumbles into the bunker, revealing their secret familial connection, while eavesdropping on the negotiations. Moon-gwang and her husband instead decide to blackmail the Kim Family by threatening to reveal their duplicity to the Parks.

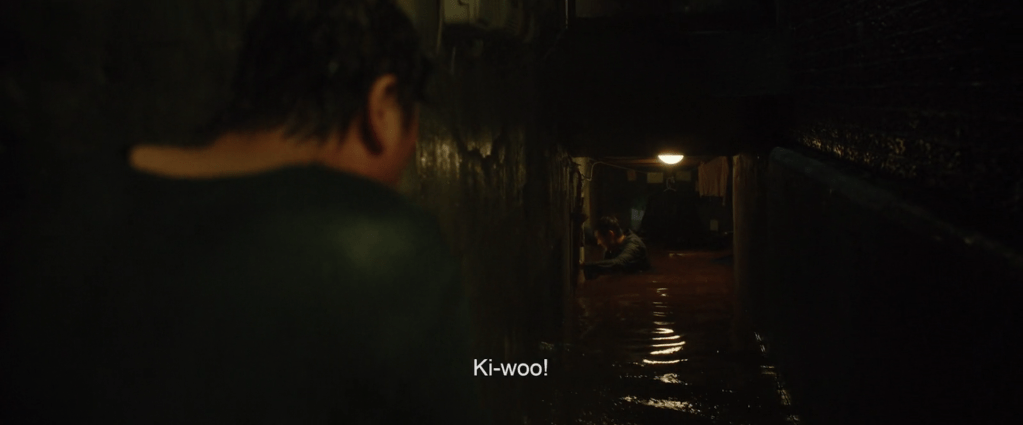

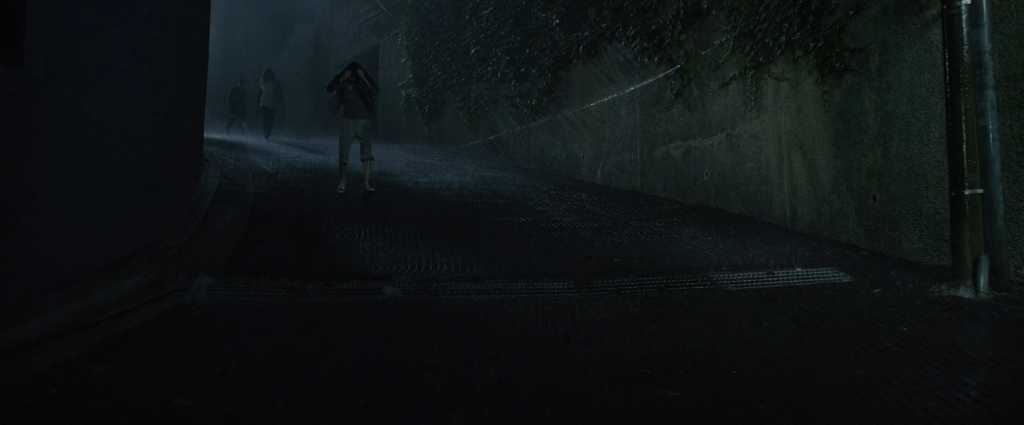

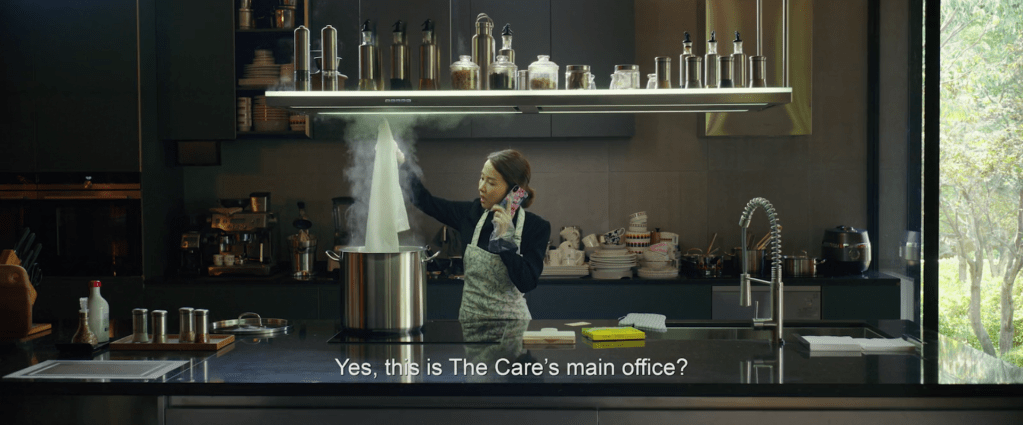

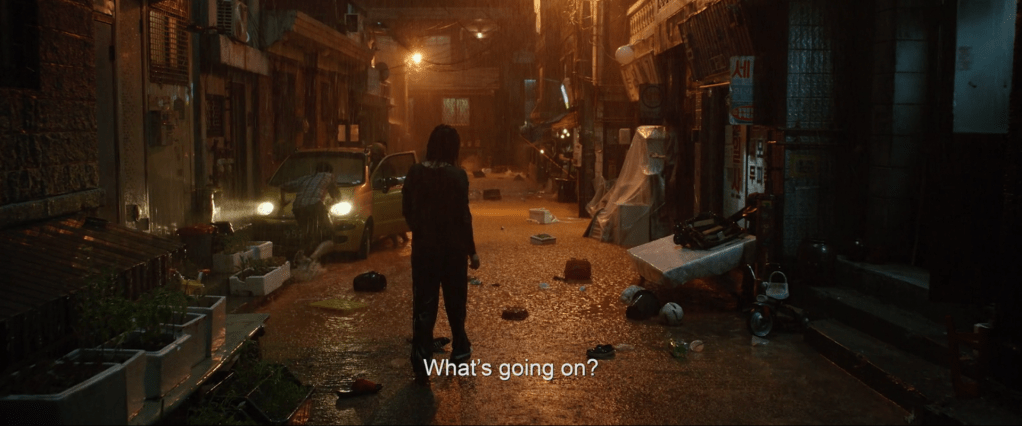

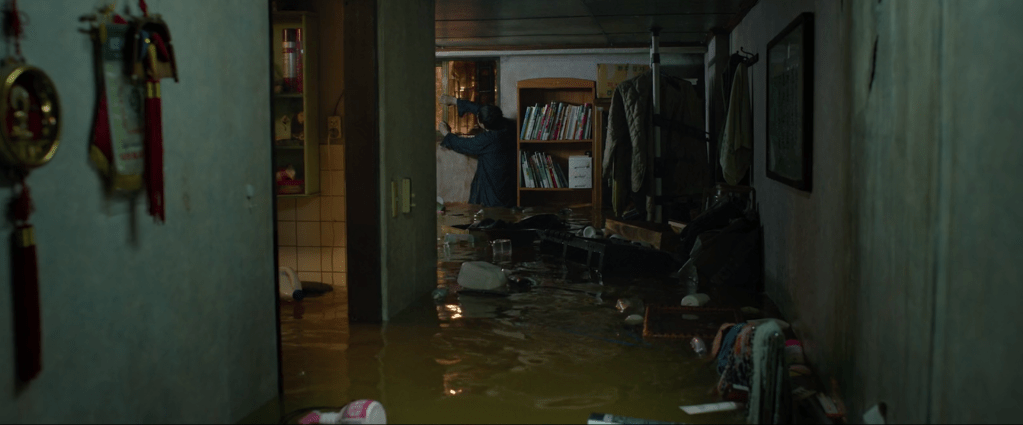

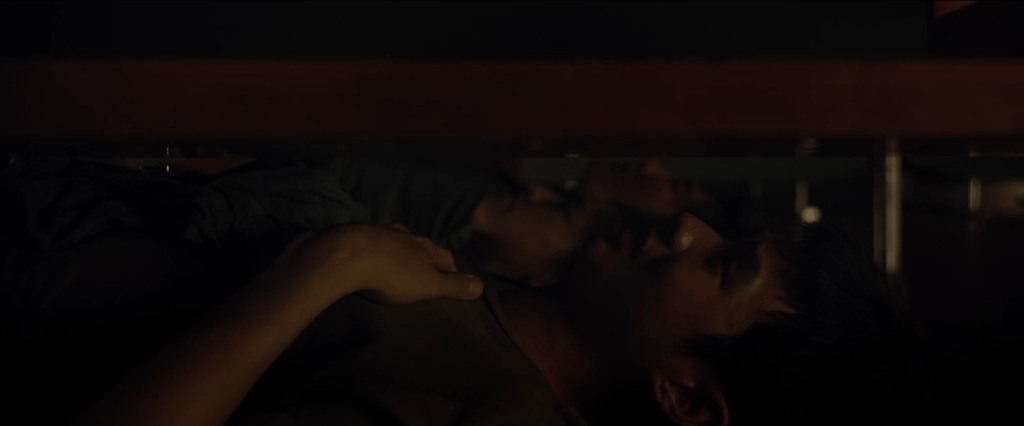

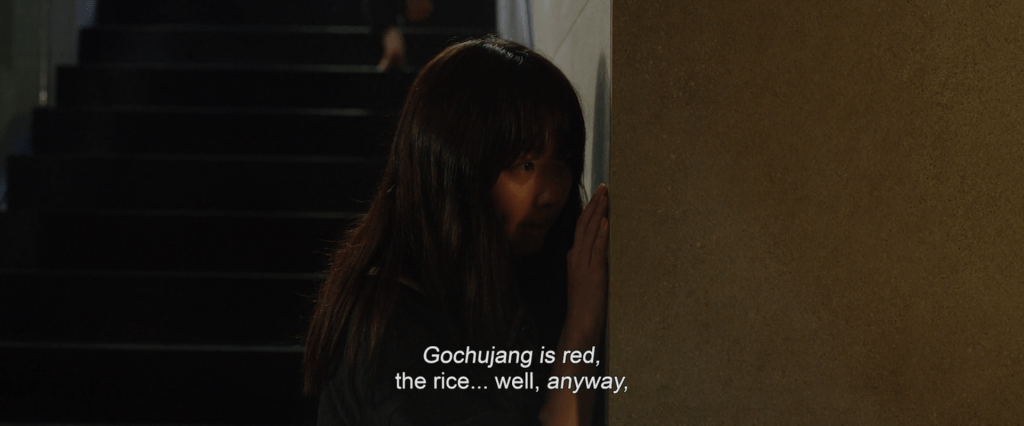

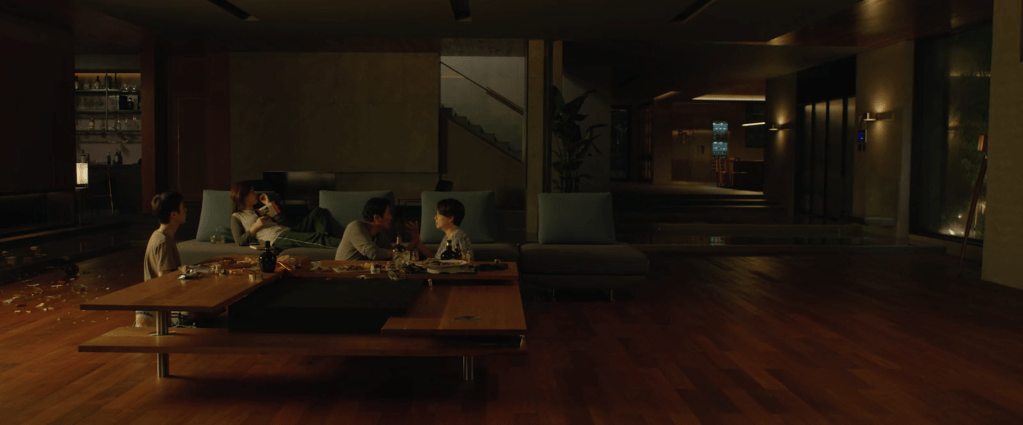

The Parks call the house, telling Chung-sook to start preparing dinner because the camping trip was cancelled due to a severe rainstorm. While Chung-sook frantically cooks, Ki-woo, Ki-jung, and Ki-taek destroy all evidence of their struggle with Moon-gwang and her husband, locking them in the bunker. Chung-sook serves dinner while her family hides under a table in the living room, later overhearing Mr. Park belittling Ki-taek’s scent which he links to the impoverished area the Kims are from. Ki-woo, Ki-jung, and Ki-taek eventually flee from the Parks’ mansion, but return home to their banjiha flooded with sewage water because of the rainstorm.

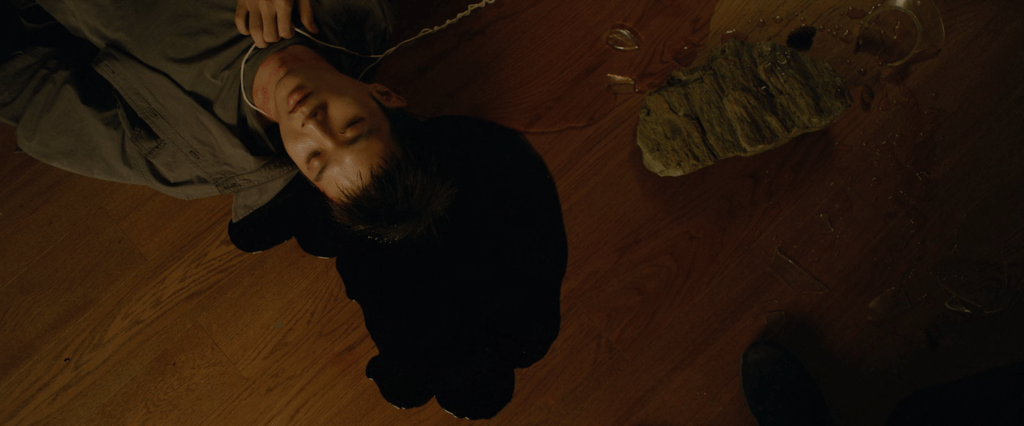

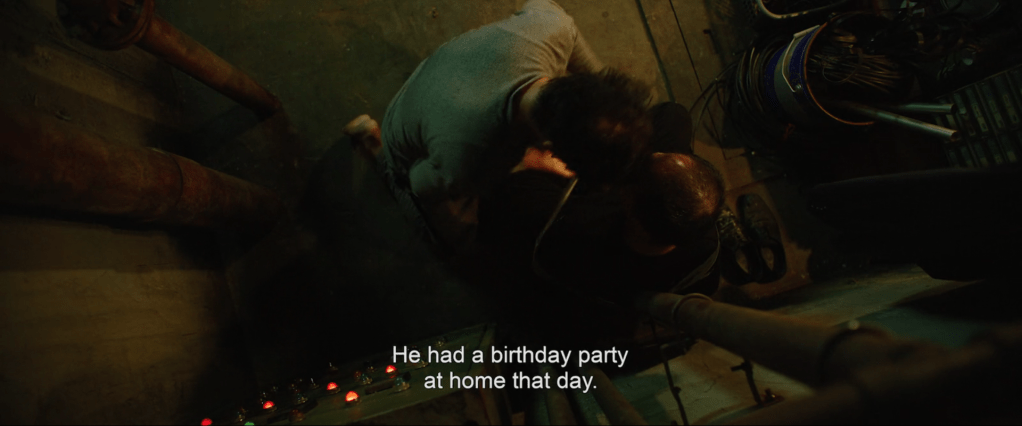

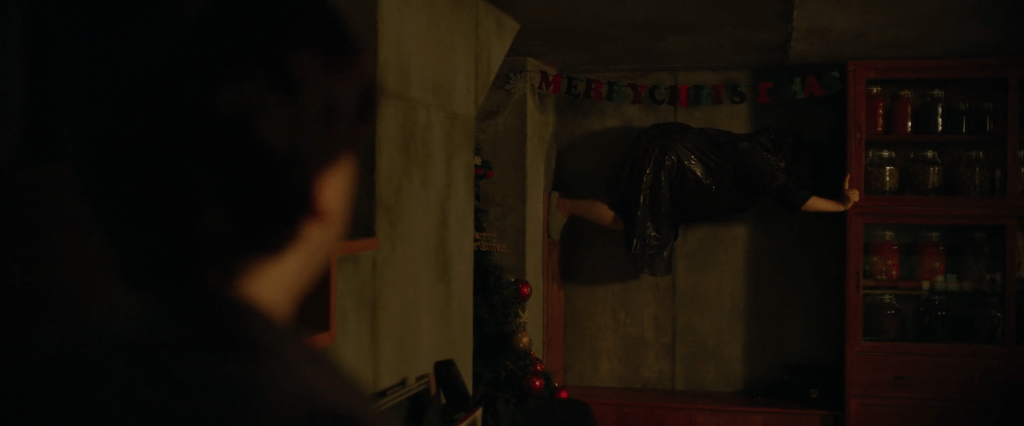

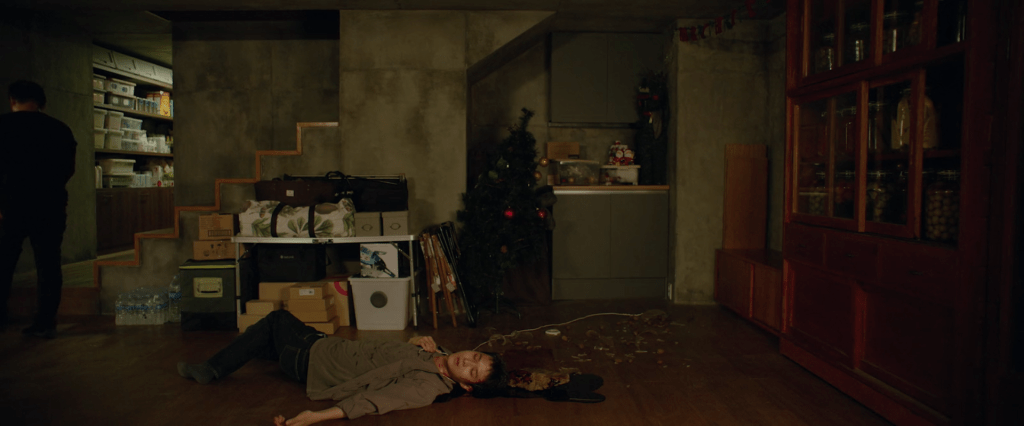

The following morning, Mrs. Park plans a surprise birthday party for Da-song to be held at their house, ordering Chung-sook and Ki-taek to work at the party and inviting Ki-woo and Ki-jung as guests. Upon returning to the Park residence, Ki-woo heads to the bunker to kill Geun-sae and Moon-gwang. He finds Moon-gwang already dead from the previous night’s injuries and is incapacitated by Geun-sae before he can kill him. Geun-sae emerges from the bunker and stabs Ki-jung in front of the party guests, leading Da-song to seize upon seeing the ‘ghost’ again. Chung-sook kills Geun-sae with a metal skewer while Mr. Park begs Ki-taek to rush Da-song to the hospital. As Mr. Park approaches Geun-sae, he holds his nose, provoking Ki-taek to kill him after remembering the comments Mr. Park made about his own scent the night before; Ki-taek escapes without a trace.

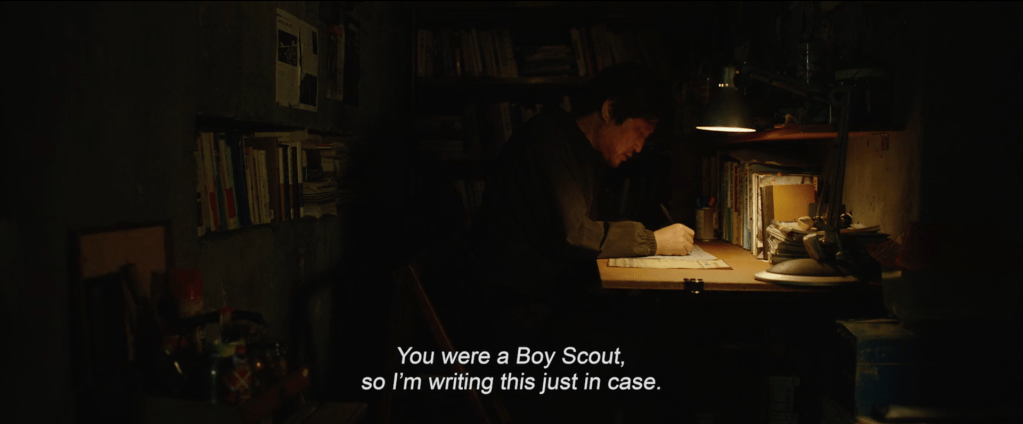

Ki-woo survives his injuries and discovers that he and his mother have been convicted of fraud upon regaining consciousness weeks after the birthday party. Ki-jung passed away and Ki-taek still has not been found. Ki-woo, now enlightened to the existence of the bunker, watches the Parks’ home after they move out hoping to find evidence that his father is still alive. He eventually observes morse code messages emanating from light fixtures in the house from his father, revealing that he has been hiding in the bunker since the events of Da-song’s birthday party. Ki-woo writes a letter to his father in response, promising to earn enough money to lift himself and his mother out of poverty through the purchase of the Parks’ old home, liberating his father in the process.

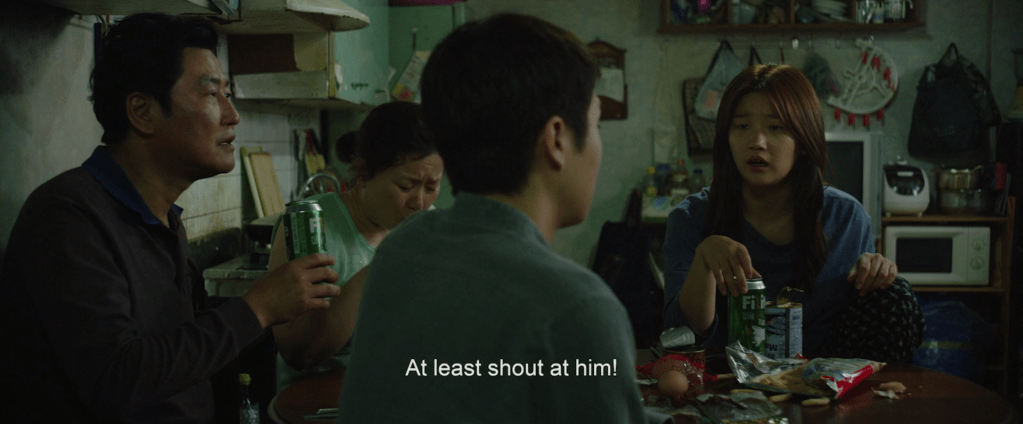

In Parasite, the architectural framing of bodies represents the oppression of the Kim Family under capitalist economic structures which restrict them to lives as domestic laborers in the home of their employer and in their own home. In this film, the definition of ‘feminine body’ extends to Ki-taek and Ki-woo because of their employment as domestic laborers, a profession historically reserved for women and gendered as feminine as discussed previously. In South Korea, “Girls and women aged 15 or older spent about two hours and 26 minutes on housework in 2019, about 3.6 times longer than men who devoted 41 minutes, according to the Seoul gender statistics report on residents’ work-life balance;”[1] Within the broad class commentary presented in Parasite lies an equally as important discussion about the gender disparity in housework responsibility, especially for women who are also employed as housekeepers of the upper class, and the capacity of architecture to symbolize this oppressive divide. Ki-taek and Chung-sook’s bodies are viewed through prison-like grates and slivers of compressed space in the film, framing their bodies as stuck and restricted to spaces in which they can perform domestic labor tasks.

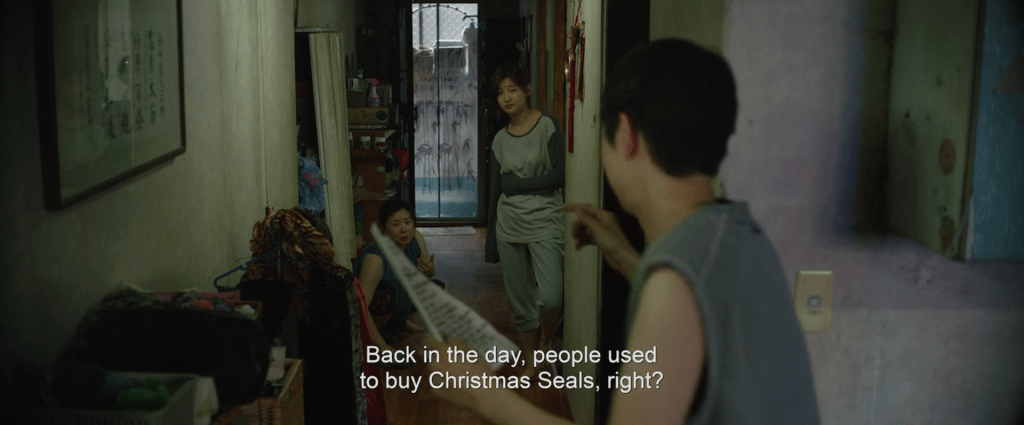

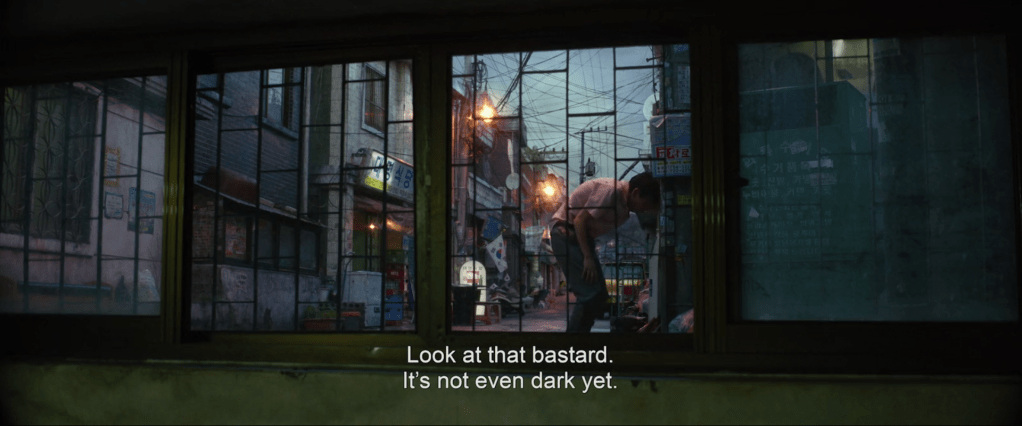

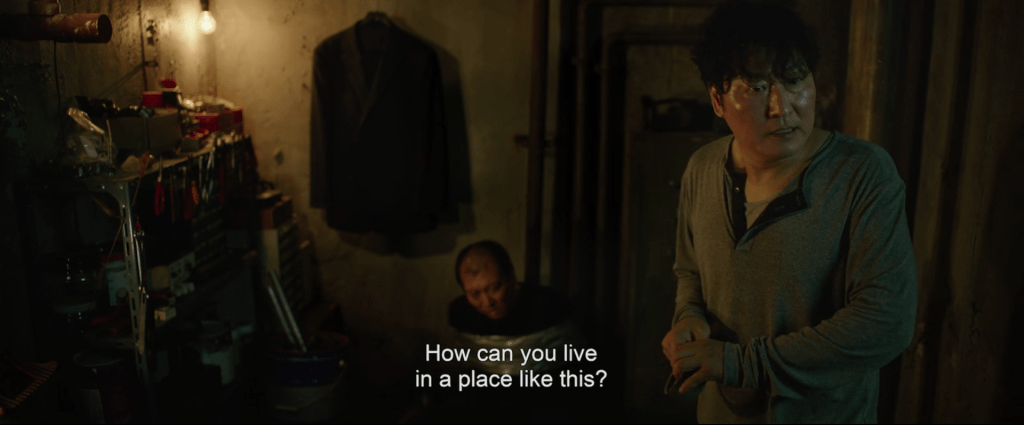

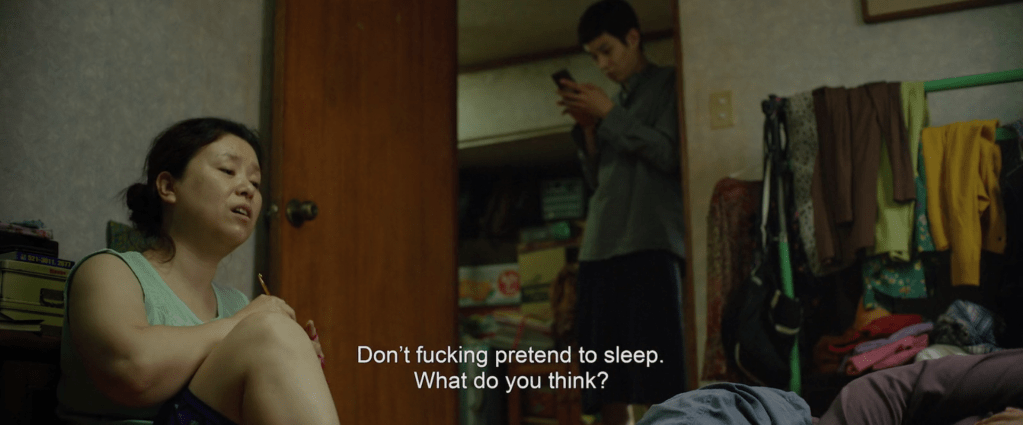

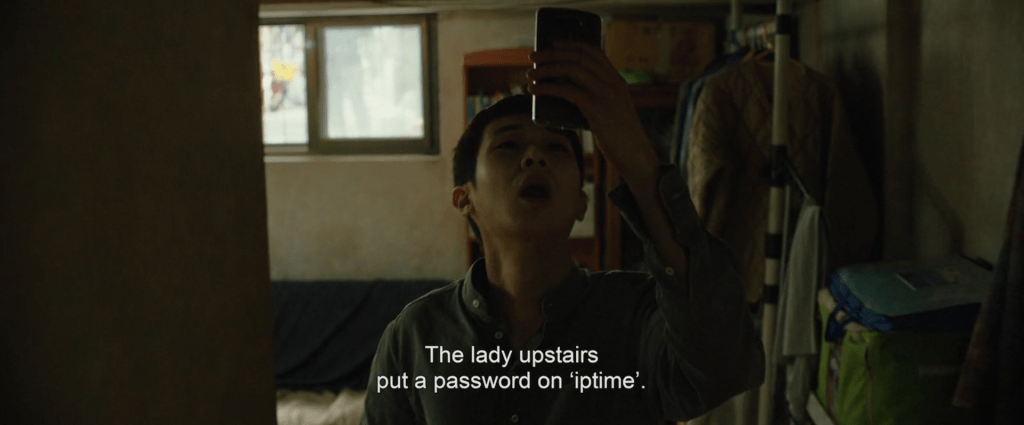

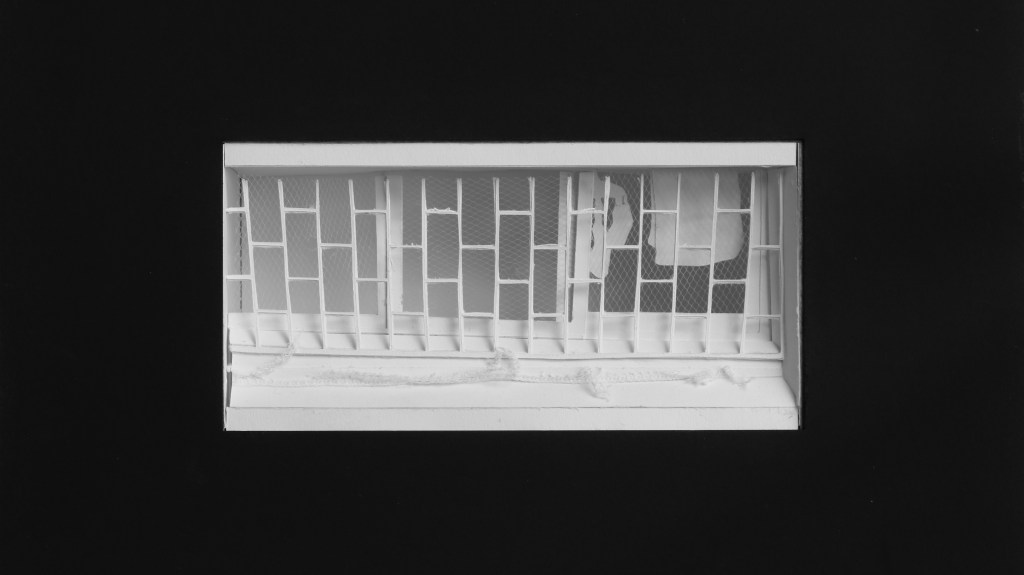

The establishing shot of the film cements the framing capacity of architecture as paramount to its argument on class disparity in South Korea by depicting the grim reality of the Kim family’s living arrangement. They live in a small, cluttered semi-basement apartment with one primary large horizontal window in the main living space. This window is the Kim family’s only view of the outside world, but because their apartment is partially underground, it only frames a small portion of the street beyond their living quarters. Through this window, the family regularly argues with a man who relieves himself on the stairs into their apartment, emphasizing the lack of respect and unawareness others have for the lives of the impoverished in Seoul.

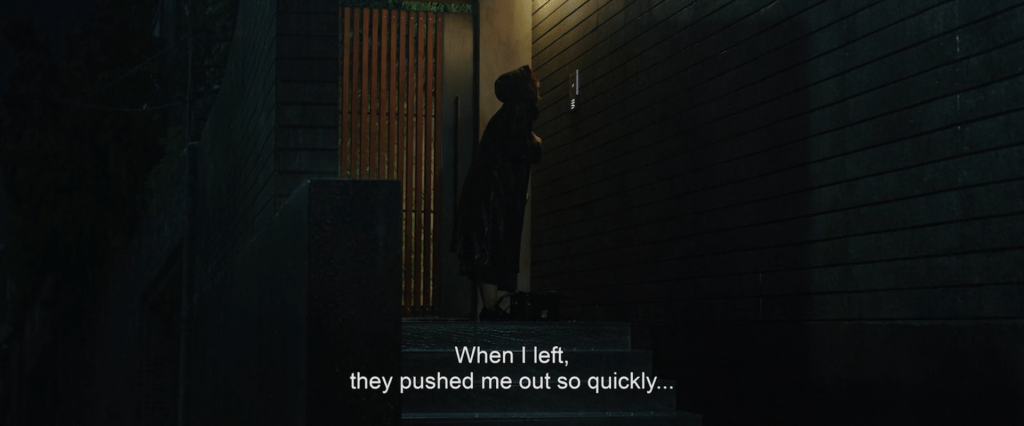

multiple screen layers comprise the window unit—the window panes, a tattered bug screen, and a metal security grate, further restricting the Kims’ view out of their apartment. Symbolically, this restricted view represents the inaccessible version of Seoul the Kims are barred from because of their economic background. The poverty they face firmly places them below ground, always looking up at a partial image of a ‘better’ life. Ki-taek is framed behind these screens at the beginning of the film, visually imprisoning him within his home and the impoverished conditions he lives under. The downwards angle of this still recreates the perspective of an outsider, looking down on Ki-taek, the Kims, and their living conditions. The camera and its framing of Ki-taek situates audience members as other residents of Seoul, viewing the economic struggle of the Kims with contempt and an air of superiority; after all, we as the audience are physically placed above the Kims in this scene.

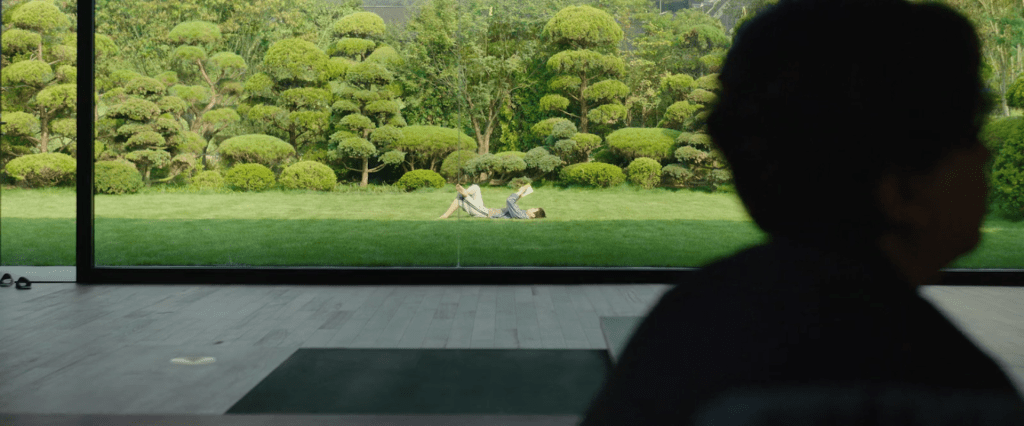

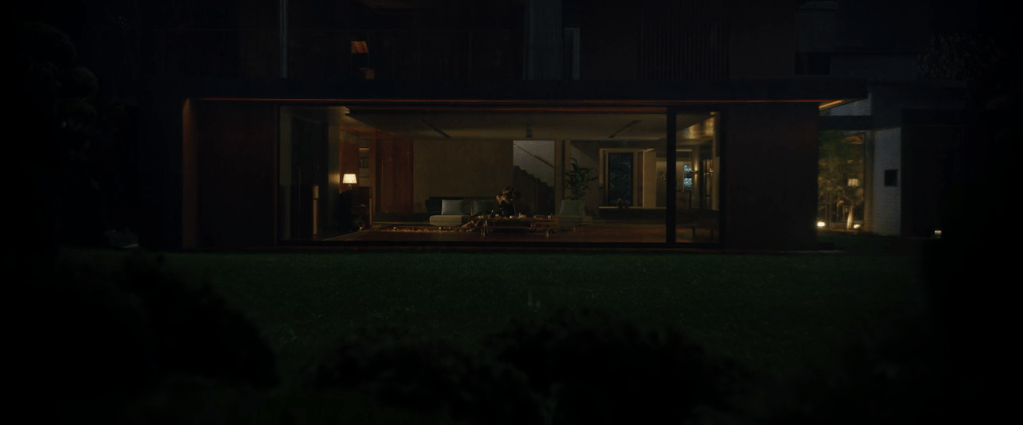

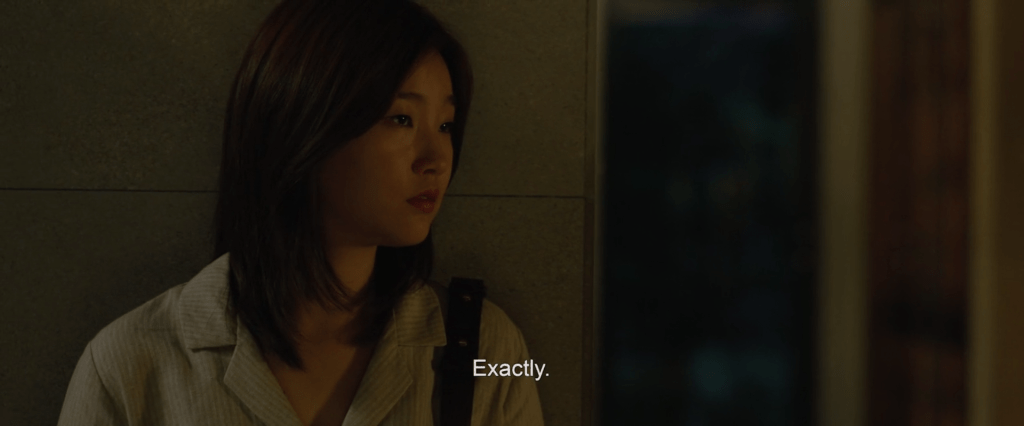

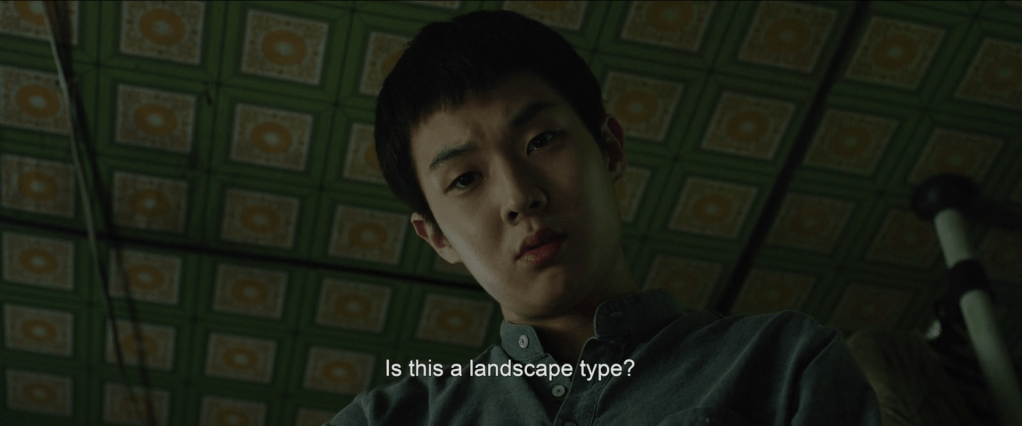

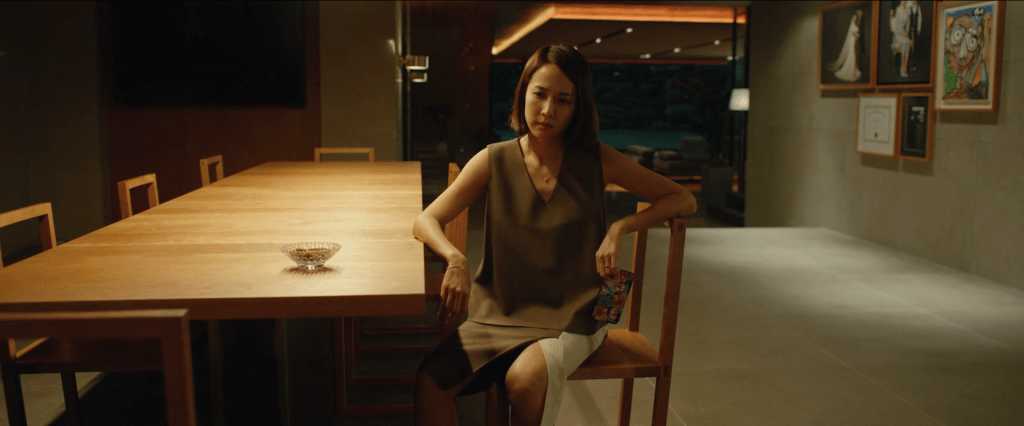

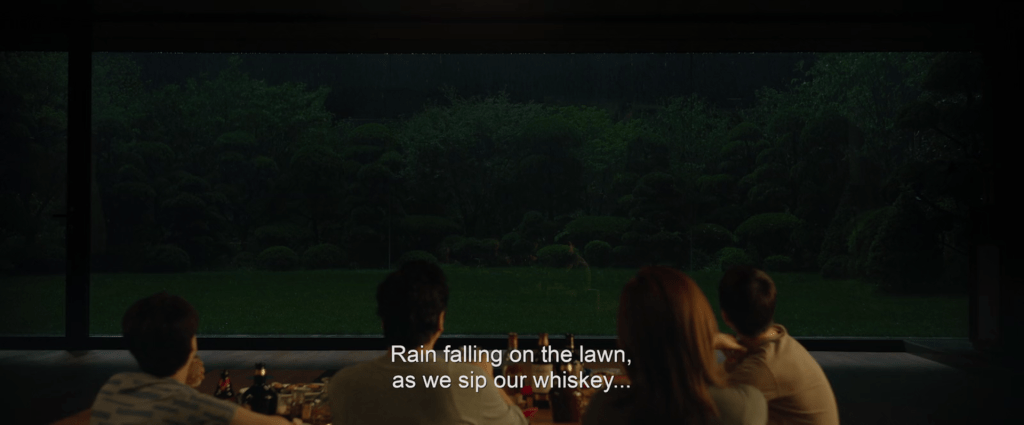

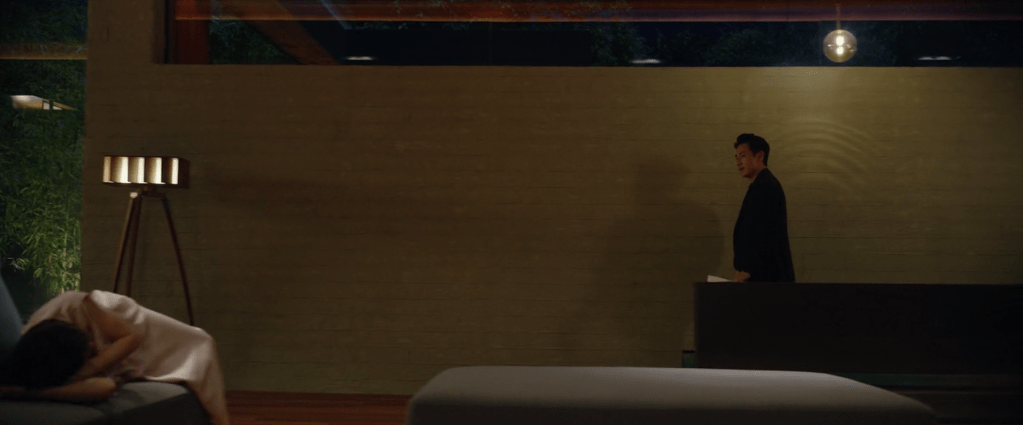

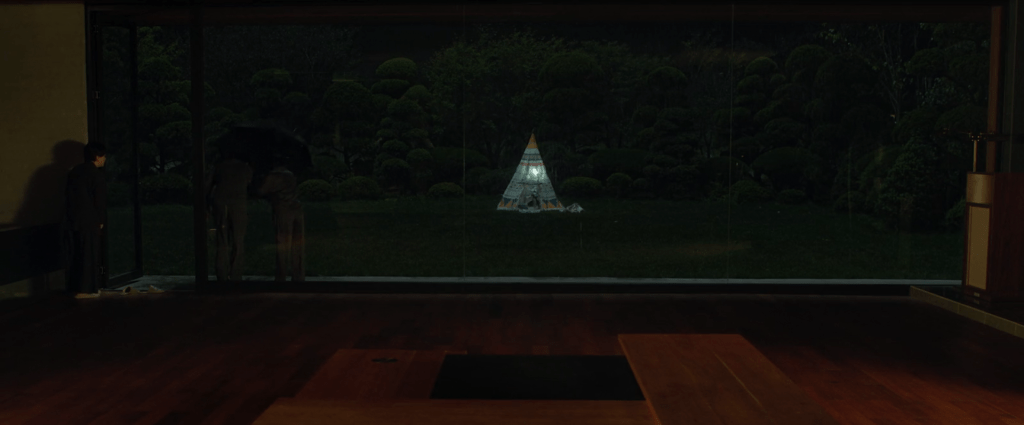

The window which frames and imprisons Ki-taek and his family directly juxtaposes a window in the home of the Parks. While the screens and obstructed views in and out of the Kims’ window architecturally represents their entrapment within a system of patriarchal capitalism which devalues household labor and service industry jobs because they are women-dominated fields. The large horizontal window in the living room of the Parks’ modernist, concrete compound is unobstructed, framing a perfect landscape planted within their backyard. Each window in Parasite frames a view into the outside world, but the Kims’ window depicts a real, ever-changing view of their environment, while the Park’s window frames an artificial landscape which shields them from the city they live in. The juxtaposition of the views framed in these windows, despite their similar shapes, highlights Parasite’s commentary upon the blindness of the wealthy class to the circumstances of the working-class world around them, even as they welcome working-class individuals into their home to aid in the education of their children and daily household chores, relieving the wealthy of their domestic duties while adding more labor responsibility into the lives of the impoverished Kim family. No matter which domestic space the Kim family occupies, they are unable to escape the constriction and exploitation of domestic labor, caged in by their own apartment. Conversely, the Parks’ access to capital allows for them to lead indolent and ignorant lives, unaware of the privilege they hold in relation to the conditions of the reality of the world outside of their home.

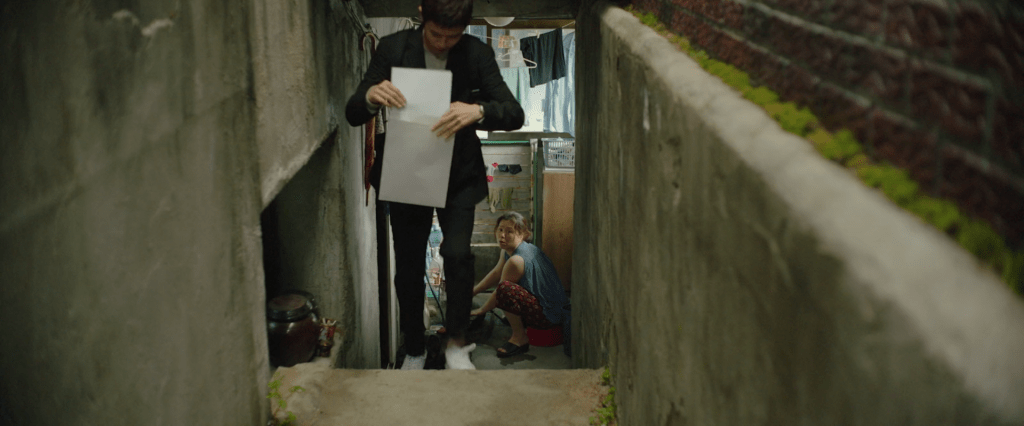

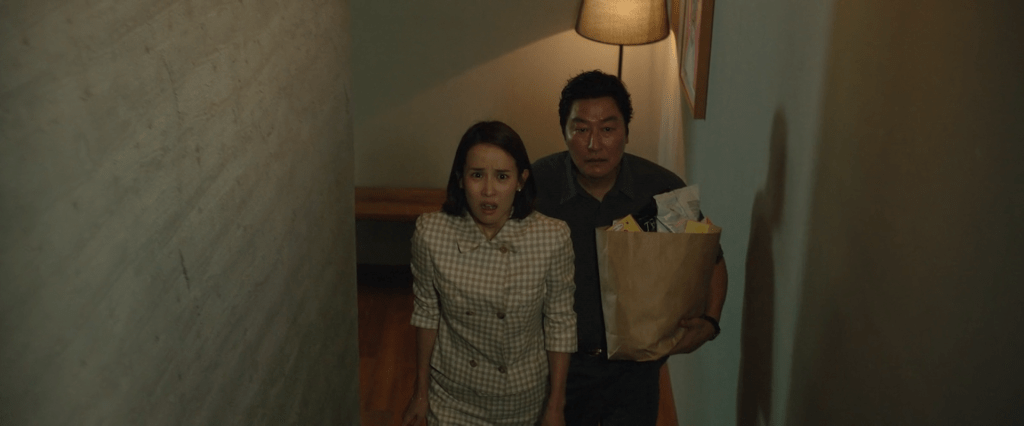

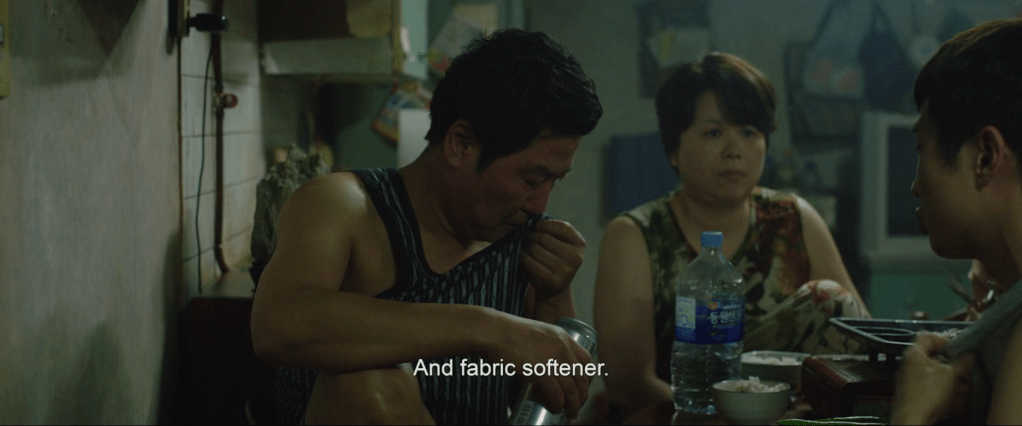

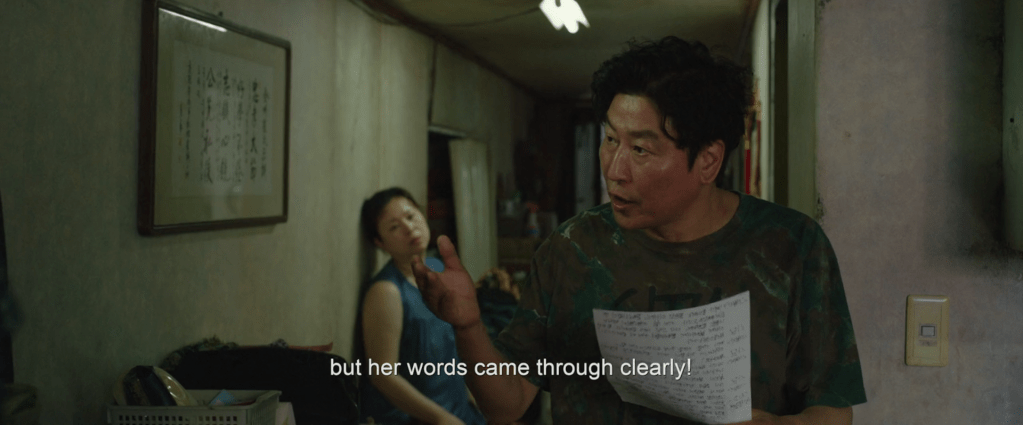

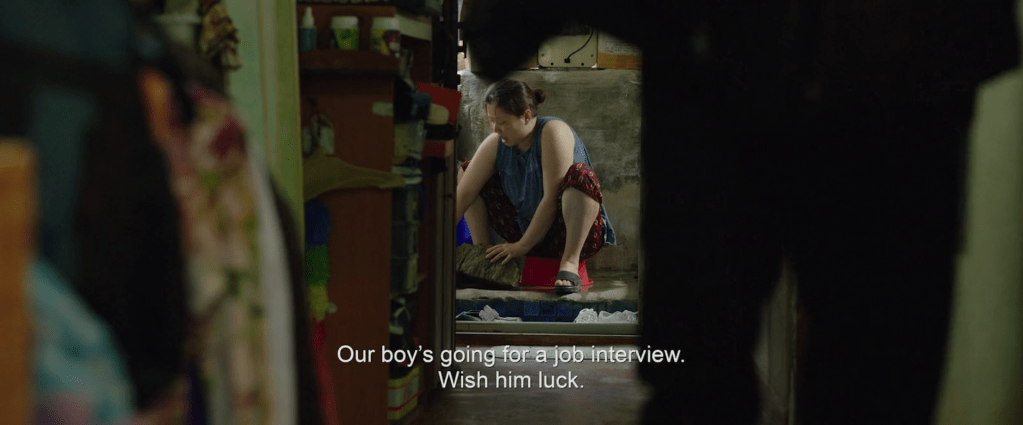

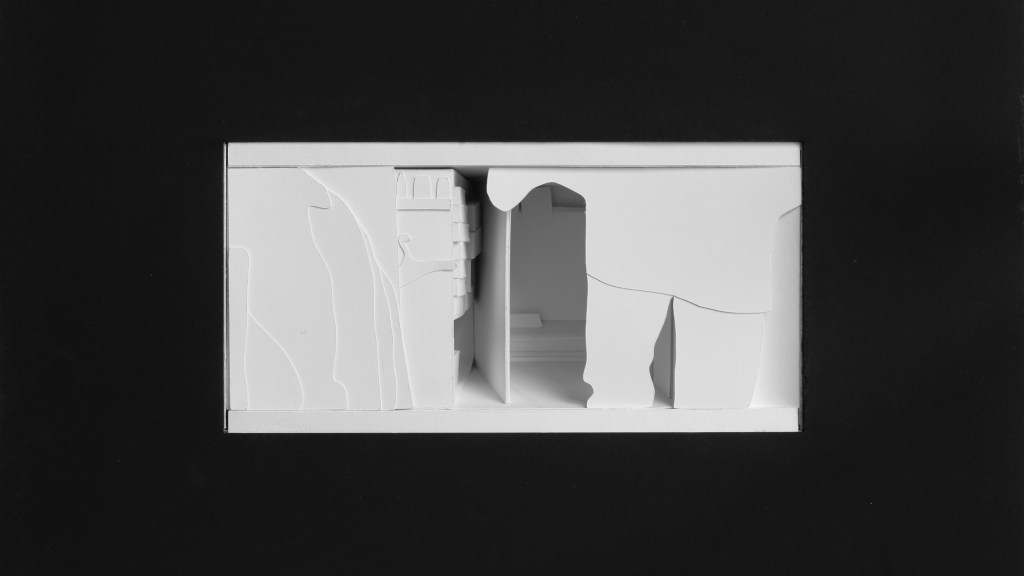

Chung-sook, the matriarch of the Kim family, in particular is unable to break free of domestic labor responsibilities; the framing of her body within a compressed doorway makes this restraint architectural. During the film, Chung-sook is seen cleaning a rock, framed within the entry threshold and corridor of the family’s banjiha. Even though she is at home, she is unable to escape domestic labor; Chung-sook is still expected to cook and clean for her family because of her role as a mother despite the fact that she is also employed as a housekeeper for the Parks to provide for her family economically. Furthermore, the space dedicated to Chung-sook’s housework at home is minimal at best (in this instance needing to leave the bounds of the apartment to clean the rock properly), again emphasizing the architecturally restrictive nature of domestic labor required of women and people in more ‘feminine’ lines of work.

Chung-sook becomes an object within the threshold of her home, a woman and mother commodified by the wealthy and her own family as a way for them to escape from domestic labor themselves. Miranda Brady emphasizes that the delegitimization of motherhood as a profession deserving of a wage, a critique shared with the second wave of feminism, stems from capitalist structures which value laborers in industry over laborers who sustain human life[2], in this example mothers. Chung-sook and her family are victims of capitalist structures and the patriarchal ideology embedded within them. To support themselves financially, they seek employment outside of their home as domestic laborers for the Park family, but because of the devaluation of housework as a legitimate line of work, the Kims are unable to escape poverty and domestic labor at home, all of which is symbolized by the architectural framing of their bodies as imprisoned and constricted within the domestic realm.

[1] Hyun-ju Ock, “Seoul women spend nearly four times longer than men on housework: report.” The Korea Herald, January 20, 2021. https://www.koreaherald.com/article/2542206.

[2] Miranda J Brady, “A Long Way from Liberation.” In Mother Trouble: Mediations of White Maternal Angst after Second Wave Feminism, (University of Toronto Press, 2024), 100.

Stills