Forbes, Bryan, dir, “The Stepford Wives.” 1975.

FILM SUMMARY

Joanna Eberhart, her two young daughters, and her husband Walter move from New York City to Stepford, Connecticut, a sleepy suburban town in direct juxtaposition to the liveliness of Manhattan. Joanna, an outspoken and artistic young woman, dreams of being a photographer and finds the move to Stepford stifling. Upon her family’s arrival in Stepford, she meets many of the other wives in town, all of whom are the epitome of ‘perfect’ housewives: youthful, beautiful, and obsesses with housework.

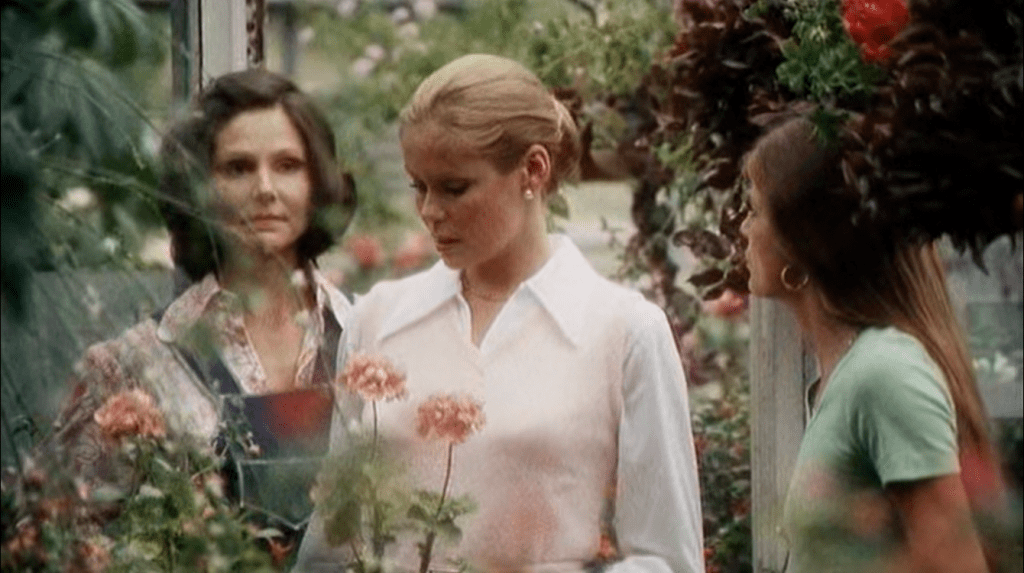

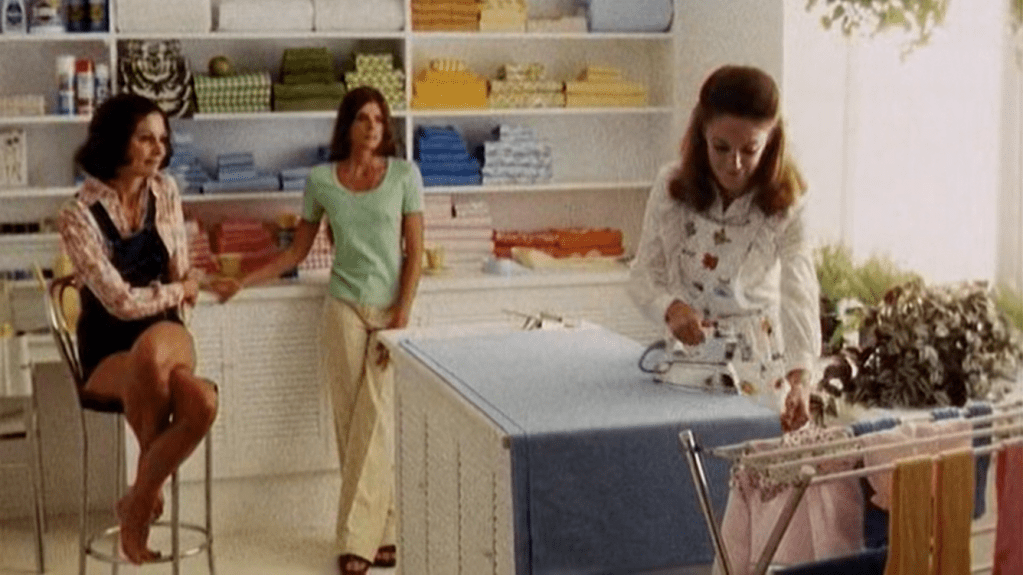

Walter joins the mysterious Stepford Men’s Association shortly after the move and Joanna is appalled by the sexist exclusionary practices of the men in town. Despite the perceived oddity of the women of Stepford, Joanna meets and becomes friends with Bobbie Markowe, another younger woman who finds the submissiveness and docility of the other Stepford wives deeply unsettling. They learn that Carol Van Sant, the most pristine of the Stepford women, used to act as president of a Women’s Liberation group in town but suddenly ceased its operations, arising more concern from Joanna and Bobbie. Determined to enlighten the other women to their misogyny-laden, oppressive lifestyles, Joanna, Bobbie, and another of their friends Charmaine organize a Women’s Liberation meeting for the women of Stepford. The meeting is ultimately unsuccessful as it devolves into a discussion about the most effective cleaning products amongst the women in attendance.

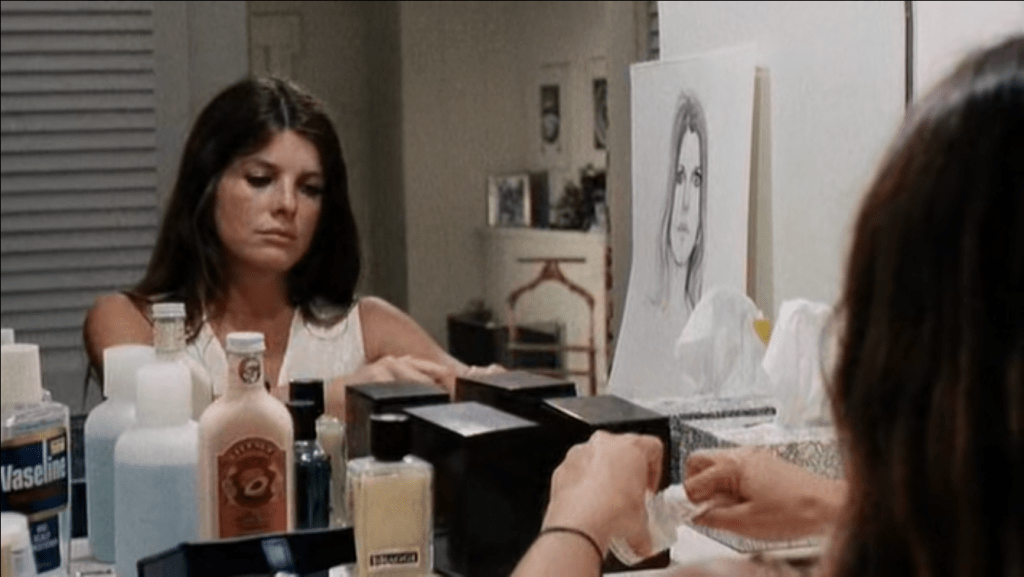

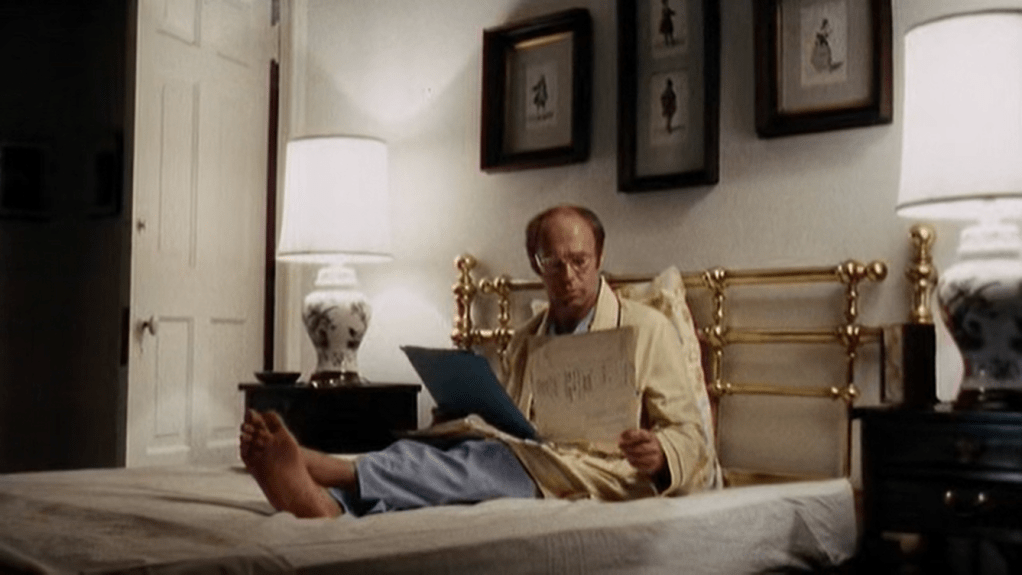

As Joanna becomes more suspicious that something sinister is occurring to cause the women of Stepford to act so submissively, Walter becomes more engrained into the operations of the Men’s Association, even hosting them at his and Joanna’s house. The men in the organization, with the help of Walter, profile Joanna, collecting recordings of her voice and producing portraits of her under an innocent guise.

Charmaine returns to Stepford after a weekend getaway with her husband and begins to act exactly like the other Stepford wives, alarming Joanna and Bobbie. Bobbie believes that the growing technology industry in Stepford might be polluting the town’s water supply, somehow eliciting this behavior in the women. The pair bring a water sample to an old lover of Joanna’s in New York City, but he is unable to find any harmful contaminants in the water.

After returning to Stepford, Bobbie asks Joanna if she can watch her kids over the upcoming weekend because her and her husband will be celebrating their anniversary; Joanna agrees. While watching not only her own children, but also Bobbie’s, Joanna is overwhelmed with the brunt of the domestic labor in the house. She eventually tells Walter to entertain the children so that she can continue to work on her photography work because she believes she has made a breakthrough. Joanna yet again returns to New York, this time to pitch her work to a prestigious art gallery and they offer to display her work. She immediately heads to Bobbie’s house when she returns to Stepford, excited to share her good news, but is met by a submissive, almost foreign version of Bobbie.

Joanna experiences a psychological break, realizing that she is the last wife in Stepford not to conform to purely domestic life, and accidentally crashes into the Van Sant’s mailbox. Walter orders her to see a psychologist and tells her that she is simply paranoid, that nothing sinister is making the wives of Stepford become perfect housewives, and critiques Joanna for not assimilating into the lifestyle of the other women because it reflects poorly on himself. Joanna sees a psychiatrist outside of Stepford and confesses to her that she believes the men and their Association are the reason for the docility of their wives. The psychiatrist believes Joanna and recommends that she moves from Stepford to safety with her daughters.

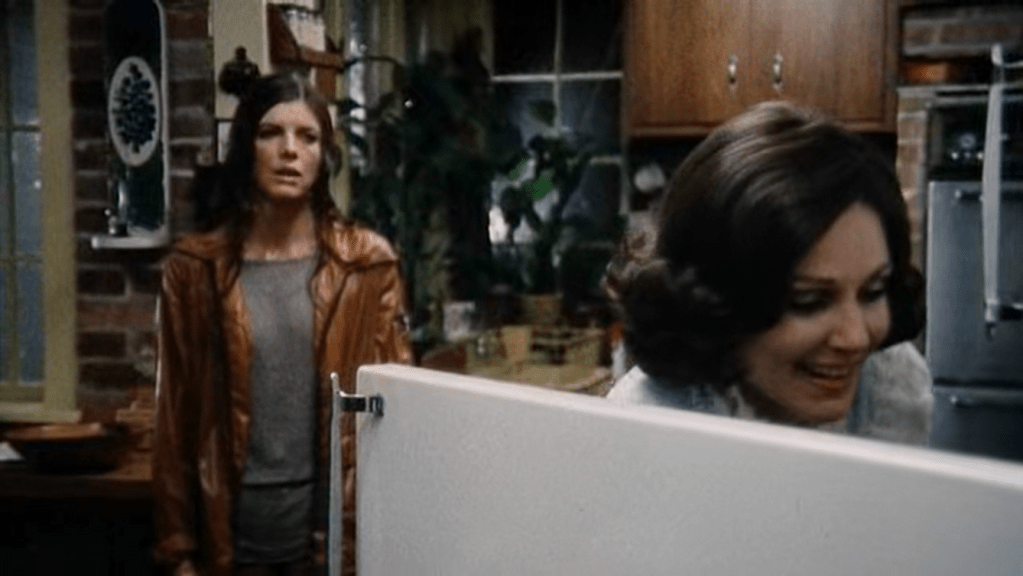

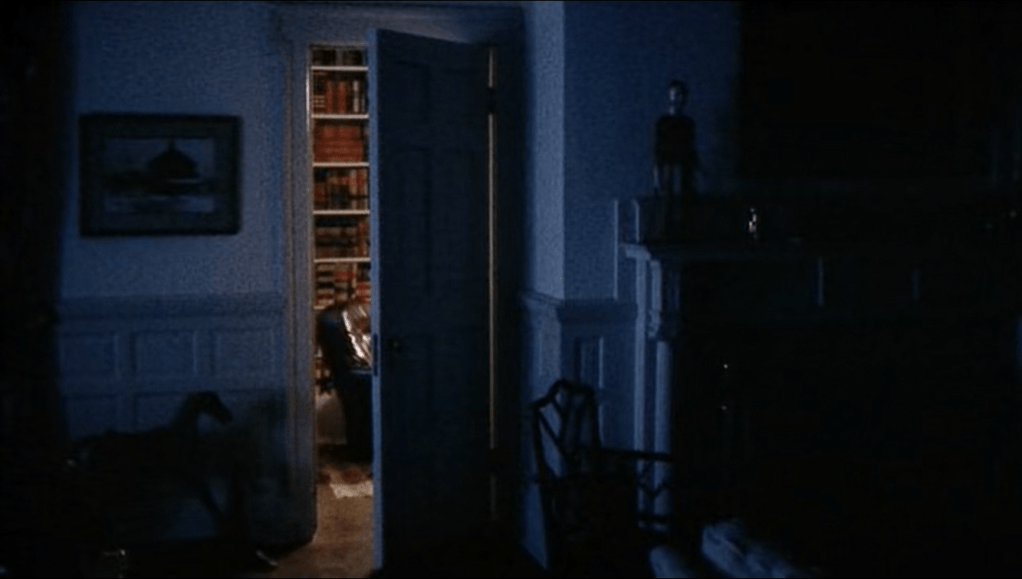

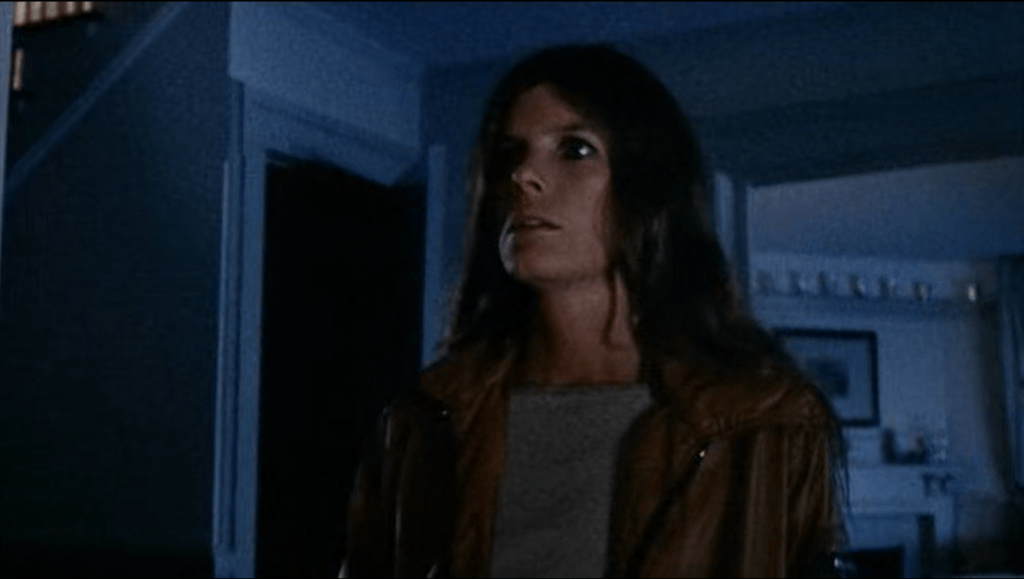

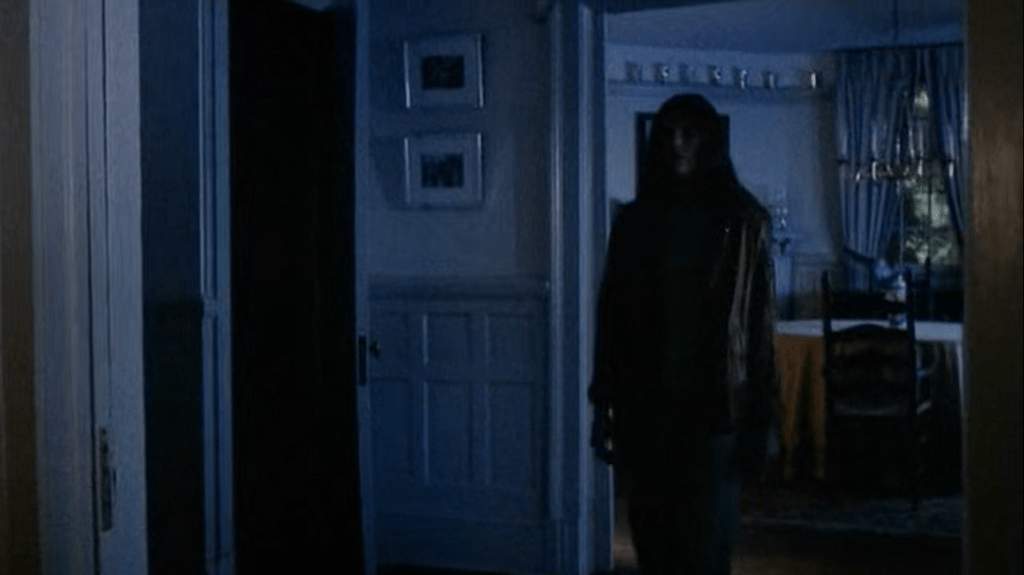

Joanna returns home to gather her children but discovers they are not home. When Walter cannot tell her the location of her children, the two fight with each other, ending with Joanna locking herself in their bedroom and later escaping to Bobbie’s house for support. Joanna, hoping to break through to the Bobbie she once knew, grows frustrated when Bobbie will only speak to her about housework. Desperate, Joanna cuts her palm with a kitchen knife, showing Bobbie that she is able to bleed, and then stabs Bobbie in the stomach. Instead of bleeding herself, Bobbie begins acting erratically, repeating herself and colliding with cabinets in her kitchen, revealing that she has been replaced by a robot along with the other Stepford women.

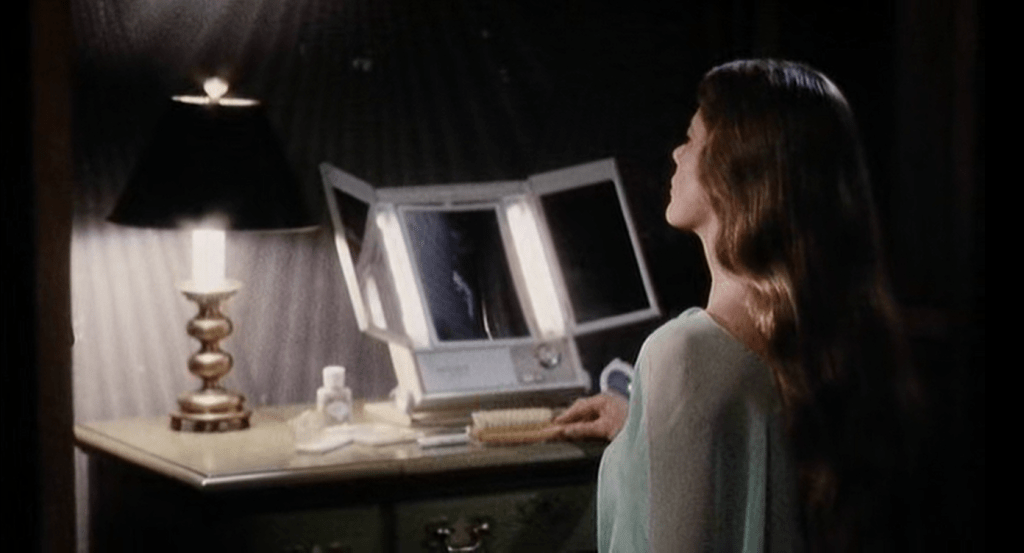

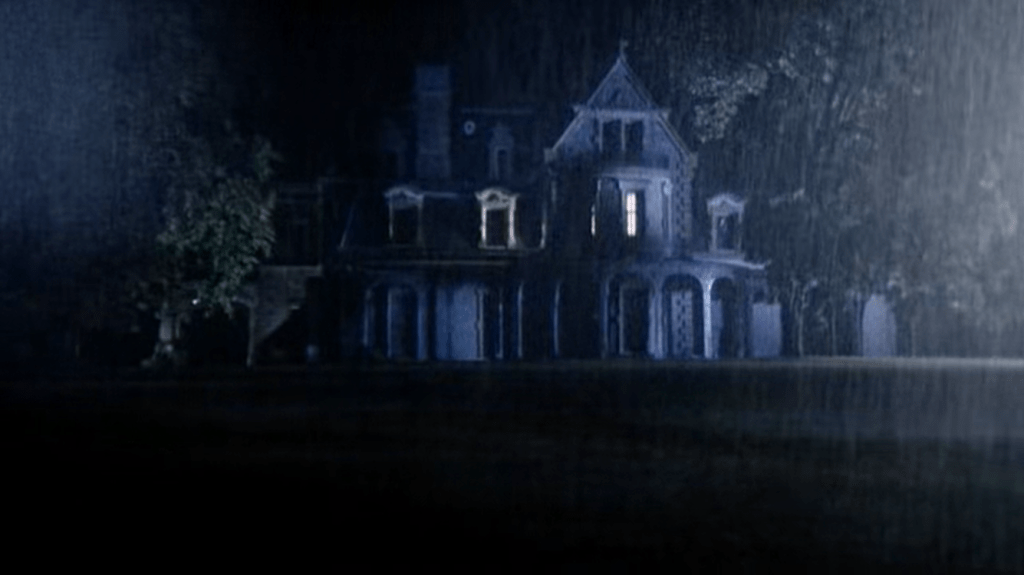

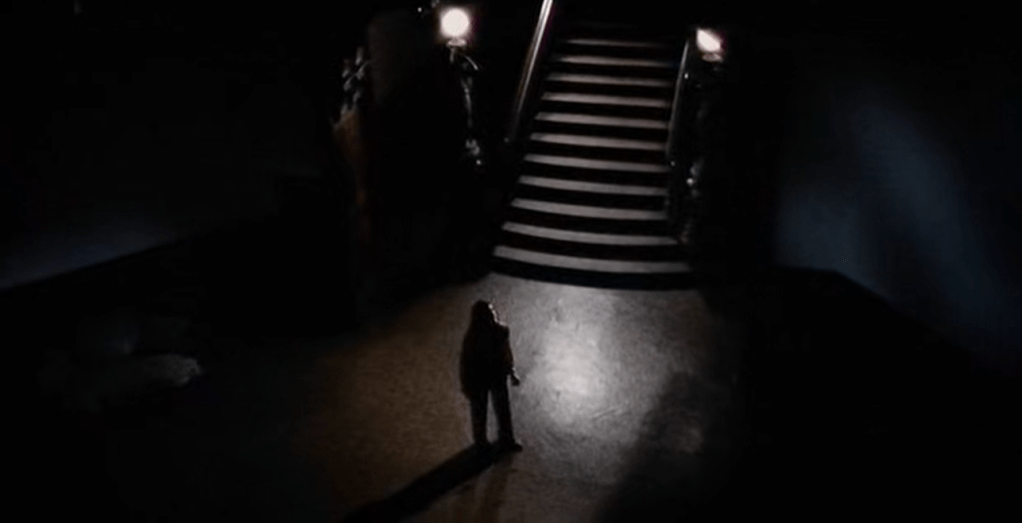

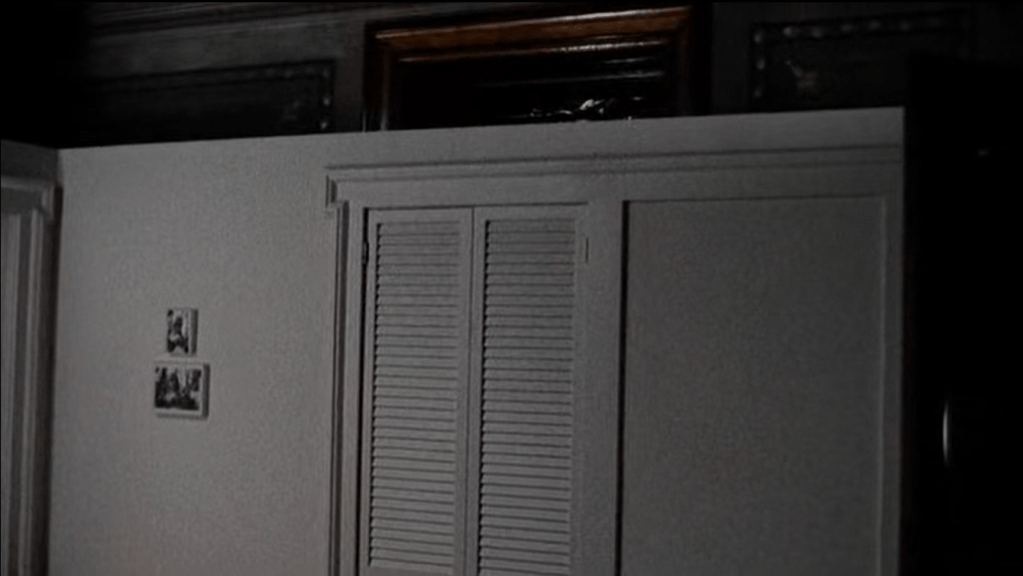

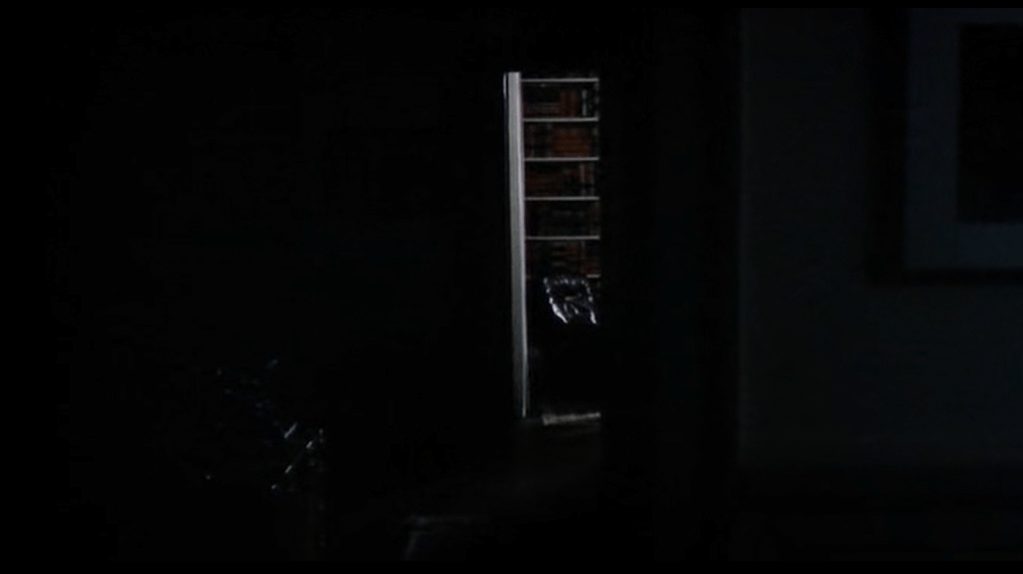

Joanna returns home one final time and attacks her husband with a fire poker before heading to the Men’s Association to find her children. Joanna secretly enters the mansion clubhouse of the Men’s Association, following the screams of her children to the main office of the building. Instead of finding her children, she finds the leader of the Association. She asks the man why they replace their wives with robots and he replies “Because we can.” Joanna attempts to escape the mansion but eventually stumbles into a recreation of her and Walter’s bedroom. Robot Joanna stops brushing its hair and approaches Real Joanna while holding a pair of pantyhose, emotionless. She strangles Joanna with the pantyhose as the leader of the Men’s Association watches.

Later, Robot Joanna aimlessly strolls through the local grocery store, emptily interacting with the other Stepford Wives as they carry out their duties as housewife robots.

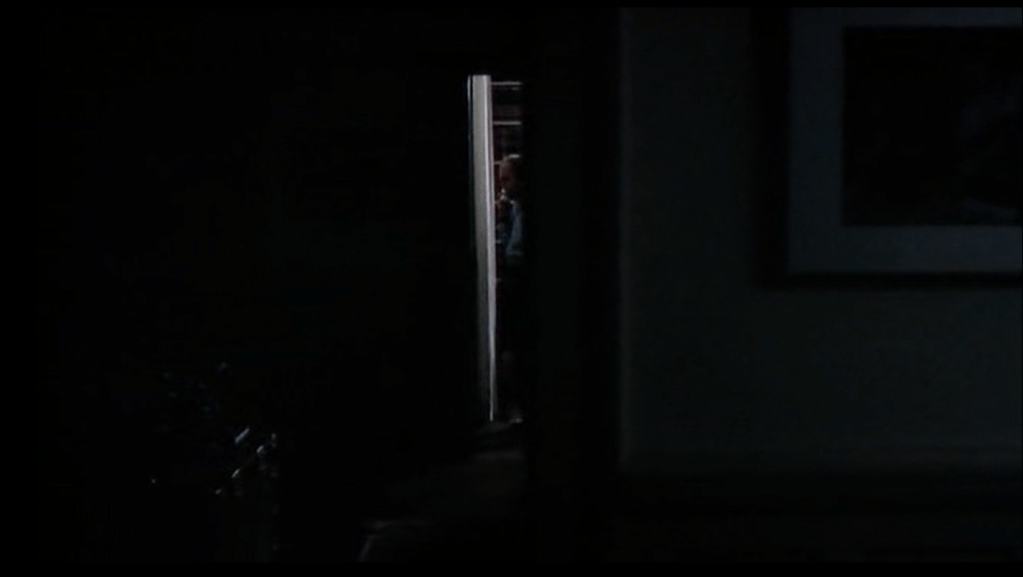

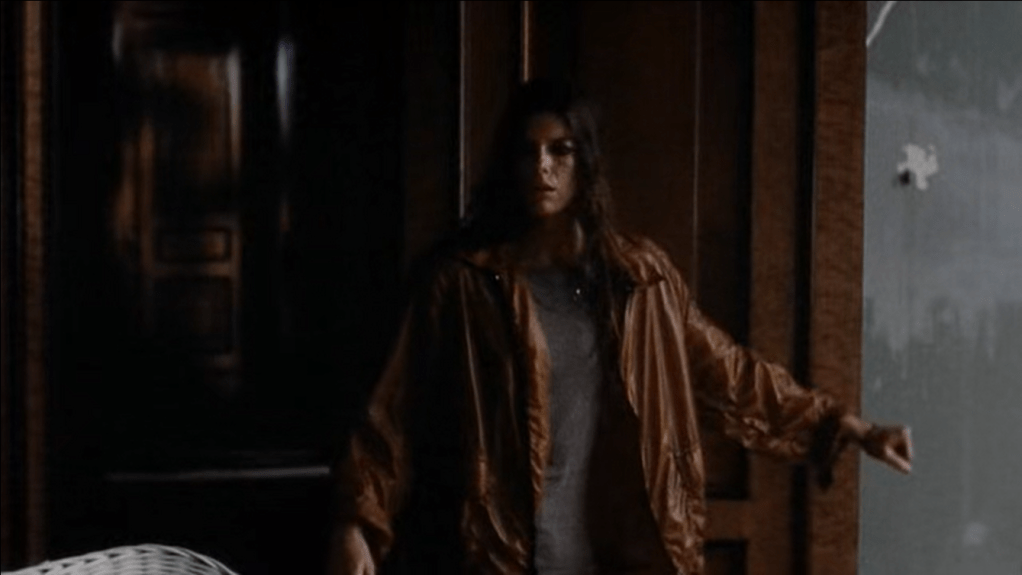

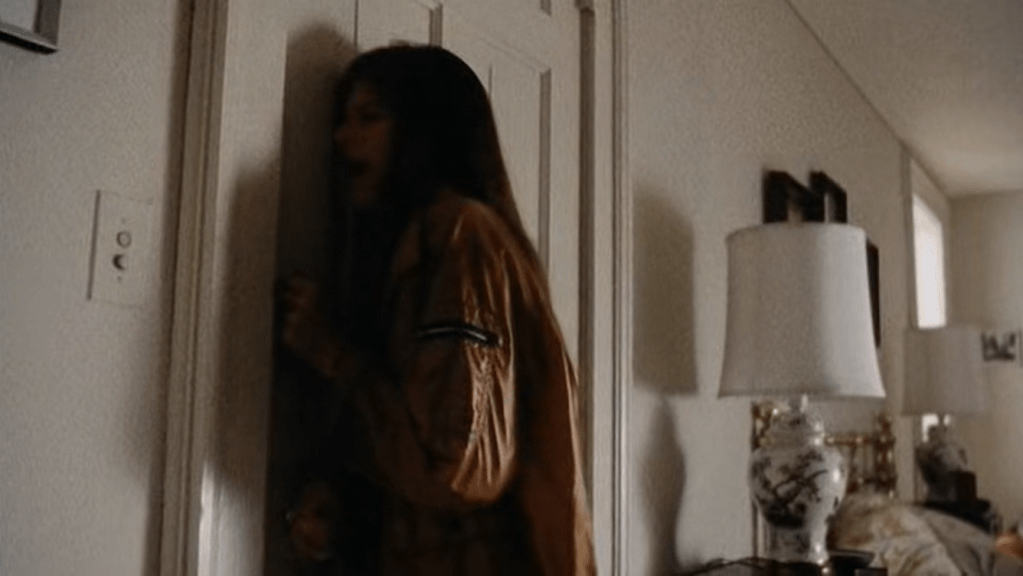

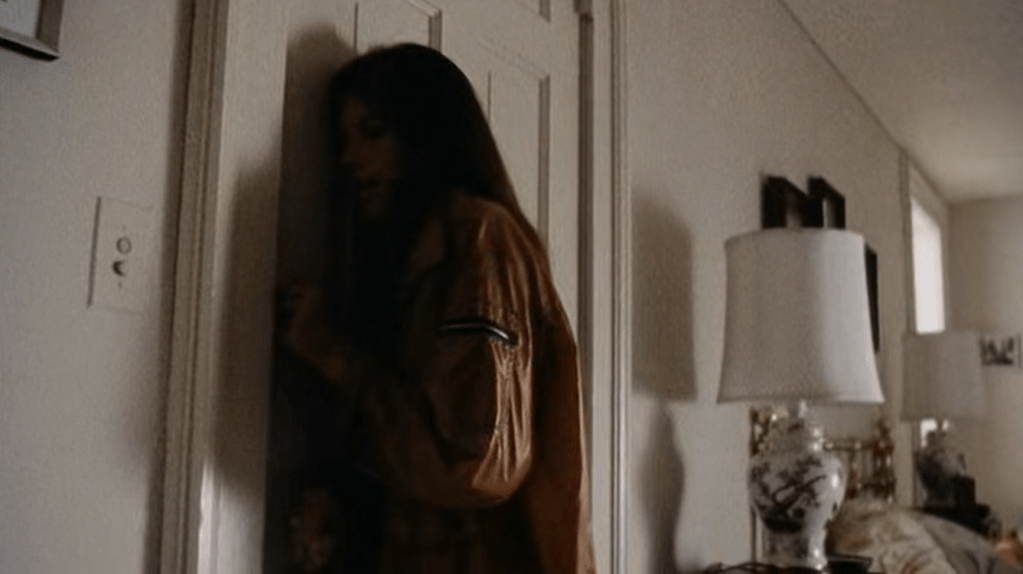

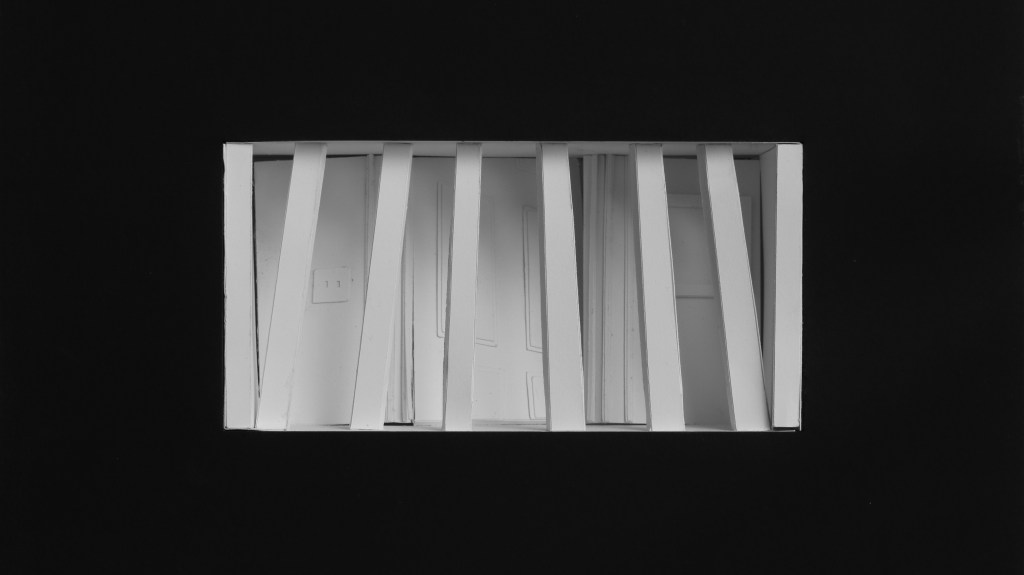

As Joanna Eberhart balances investigating the ‘utopian’ microcosm of Stepford with resisting her domestication, the spaces around her frame her body to visually symbolize her imprisonment within suburbia. More specifically, Joanna’s body is continuously obstructed by vertical members and compressed into architectural frames smaller than the film’s aspect ratio, both symbolizing her entrapment within both her home and the societal expectations of women to perform as perfect housewives that the Stepford community enforces. The two respatialized stills from The Stepford Wives highlight these framing strategies to further dissect their connection to broader critiques of feminine domestication raised in the film.

Throughout the film, Walter attempts to domesticate Joanna. He removes her from New York City, severing her from opportunities to continue practicing photography professionally. He isolates her in a silent idyll, making her solely responsible for taking care of their children and their new home while he commutes back into the city daily for work. Joanna resists Walter’s taming of her spirit, she consistently tries to liberate herself from the role of housewife that both Walter and Stepford have imposed onto her. Miranda Brady explains that “…[Joanna] insists she will never become an ‘asking-to-be exploited patsy’ like the ‘hausfrau’ who lives next door, she, like all the women around her in the suburbs, will become a Stepford wife… This seems to be a condemnation of marriage and the suburbs, which Friedan referred to as ‘the comfortable concentration camp’…”[1] Joanna’s failure to escape is the linchpin to the central feminist argument of both The Stepford Wives and the second wave of feminism in which the story was written, that the societally adopted expectation for women to perform as mothers, wives, and housekeepers simultaneously holds them prisoner to their homes.

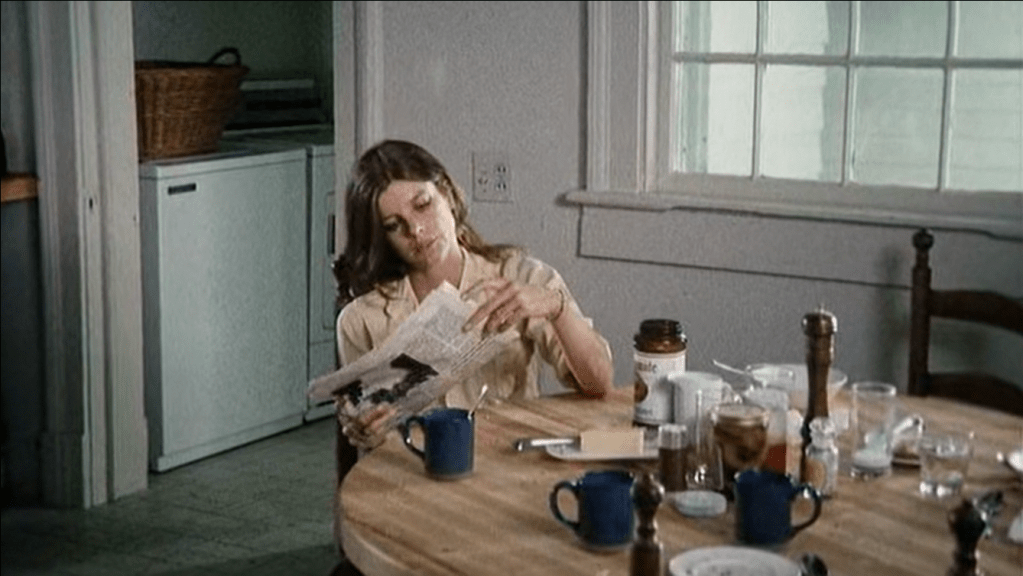

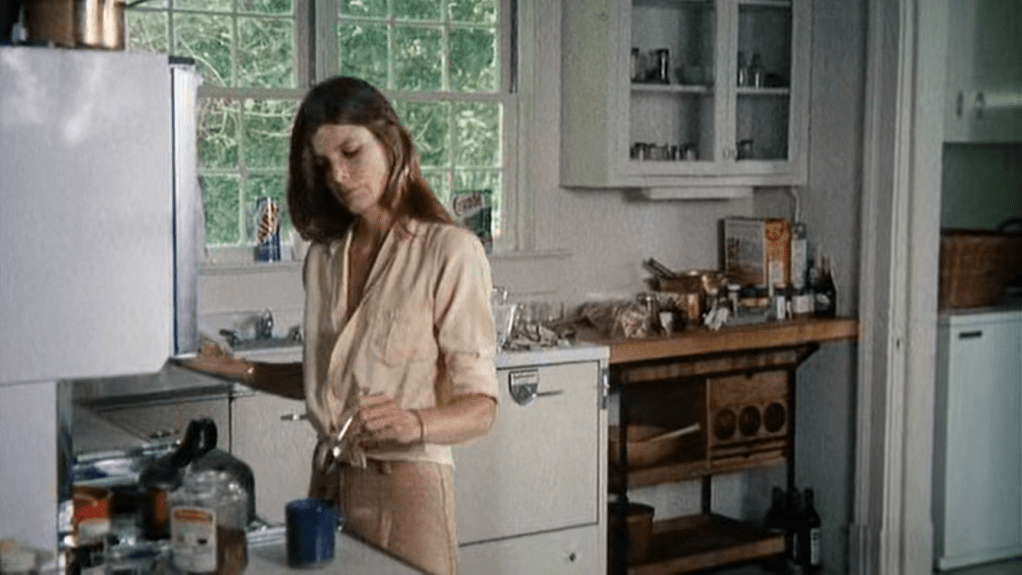

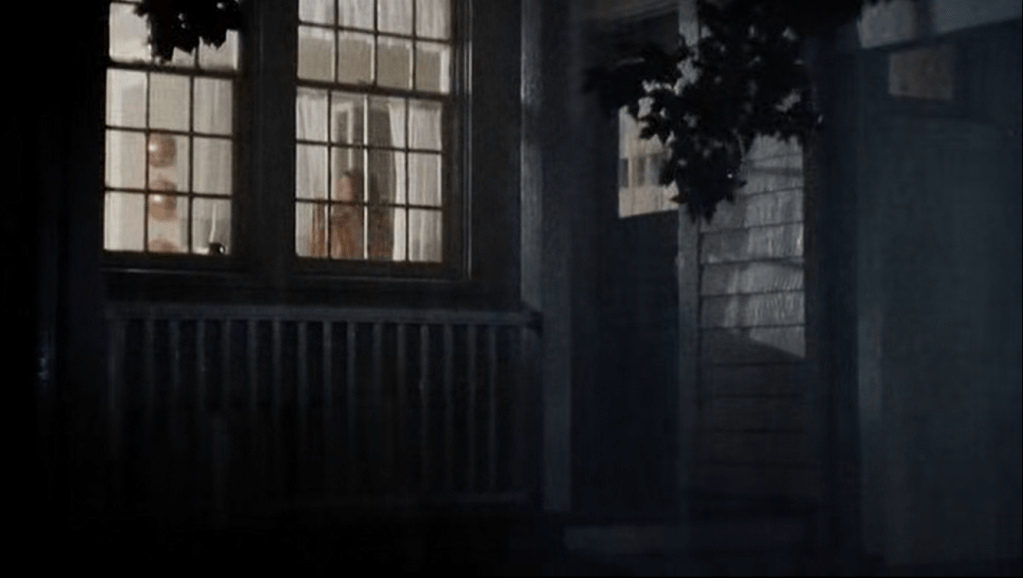

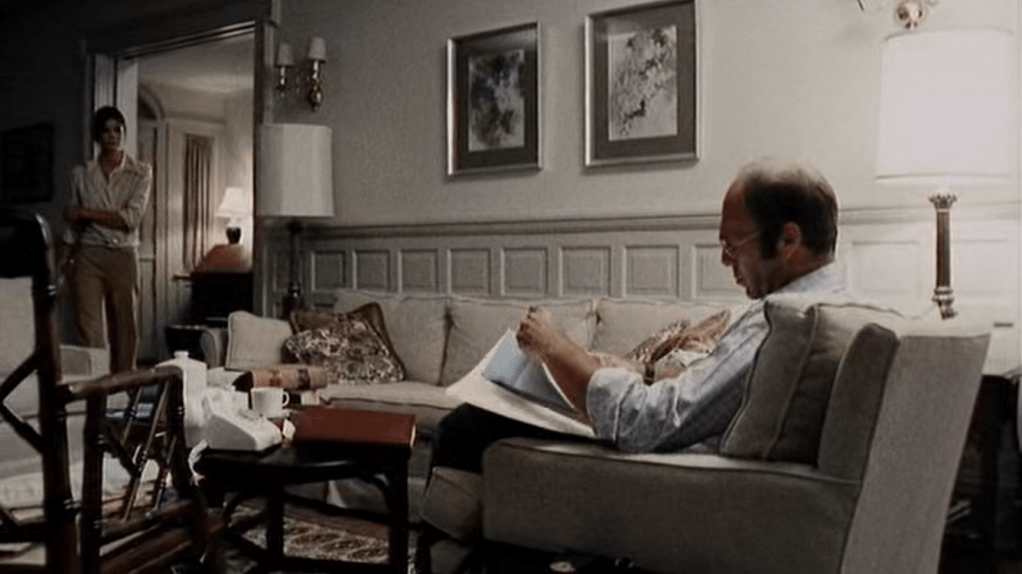

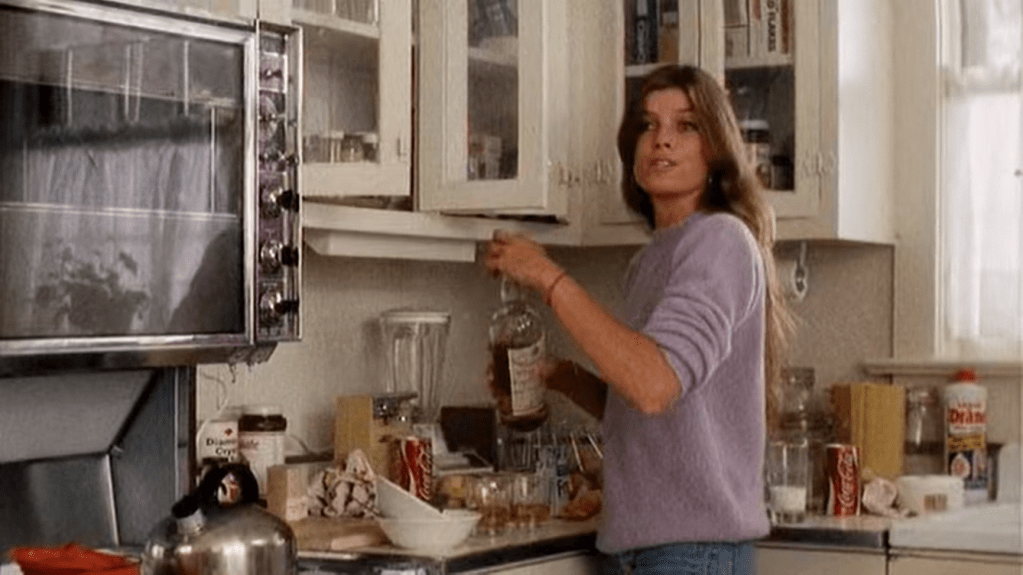

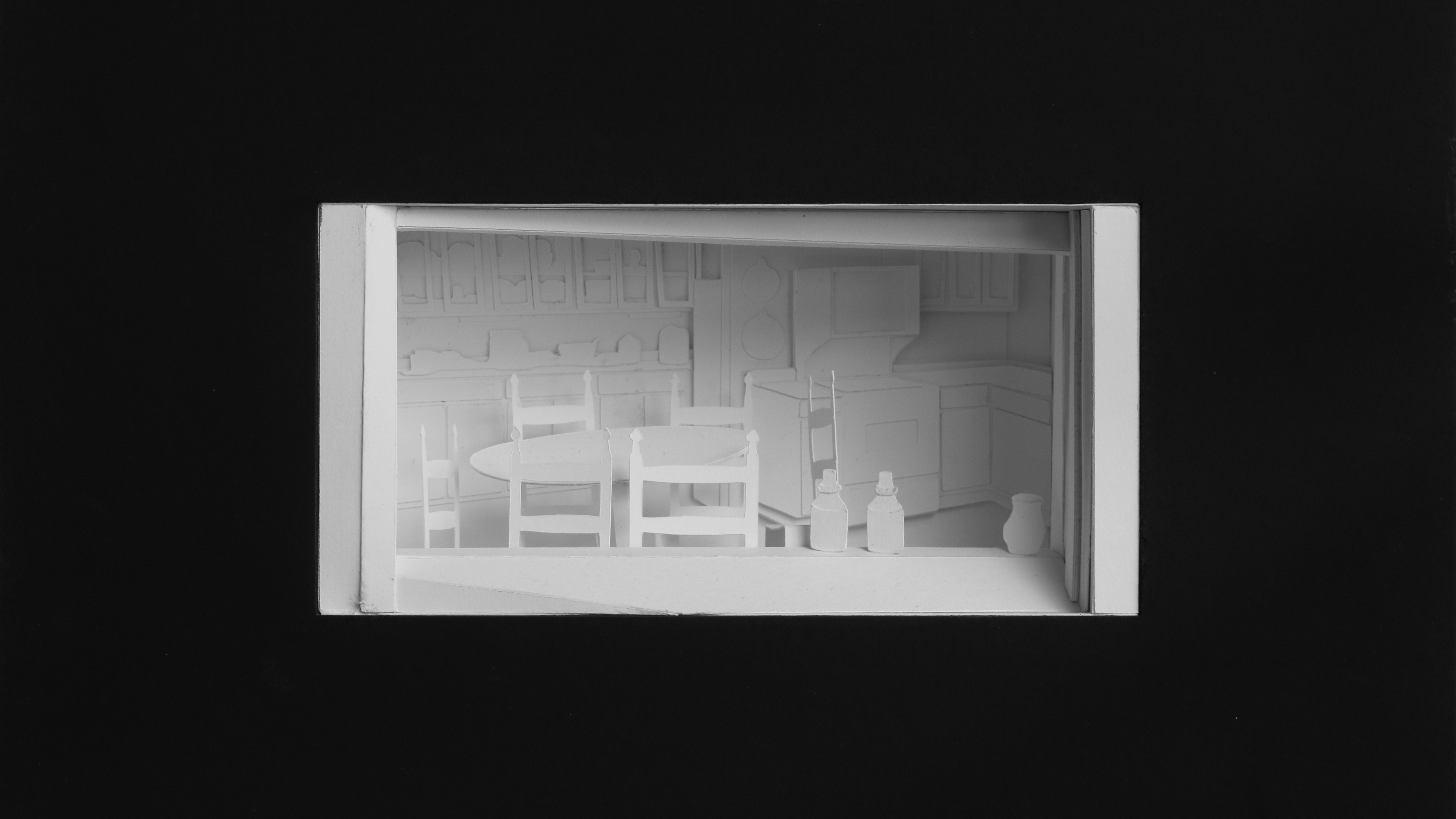

Joanna’s domestic incarceration by both her husband and the suburban social norms of the mid-20th Century embodied to their extreme by Stepford becomes architectural during a scene in which Joanna is preparing breakfast. Joanna volunteered to watch Bobbie’s children for a weekend, filling her house to the brim with beings relying on her to care for them. A window into the kitchen frames Joanna as she flips pancakes for a tableful of children and her husband, all beckoning her to feed them faster.

The sizzling griddle, whistling kettle, barking dog, crying children, and shouting husband already make this scene tense via cacophony, but the narrowing of the frame in which Joanna is visible adds to the anxiety depicted. Joanna is flanked on all sides, sandwiched between the oven range and kitchen table, unable to move from her position in the space. Her body is bound to the kitchen not only by the spatial blockades in front of her, but also by their symbolic representation of the restricted life of the housewife. Joanna not only feels entrapped by the domestic environment but also is architecturally restricted within it.

The framing of Joanna within a window frame also places the audience just beyond the threshold of the domestic world the Eberharts occupy, forcing a voyeuristic role upon us as viewers. We, in the framing of this scene, become no better than the men of Stepford, finding pleasure in watching Joanna complete domestic chores. We transform into the societal eye which surveils Joanna, making sure she performs like a perfect housewife and shaming her when she fails. We adopt the mindset of the patriarchy, the broader force which imprisons Joanna within her home. Pioneers of the second wave of feminism advocated against this ideological equating of ourselves with patriarchal masters:

We want and have to say that we are all housewives, we are all prostitutes and we are all gay, because until we recognize our slavery we cannot recognize our struggle against it, because as long as we think we are something different than a housewife, we accept the logic of the master, which is a logic of division, and for us the logic of slavery.[2]

Silvia Federici, like Betty Friedan, recognized and critiqued the patriarchal ideals which exploited women’s bodies as domestic laborers and incarcerated them within their own homes, slaves to their husbands and children because they had historically been expected to as housewives. The inherent voyeurism of the framing of Joanna’s body within the kitchen window uses architecture to make us aware of the broader societal acceptance of patriarchal ideology. We see her from the point of view of the ’outside,’ the masculine eye that aims to domesticate women by separating them from the world outside of suburbia.

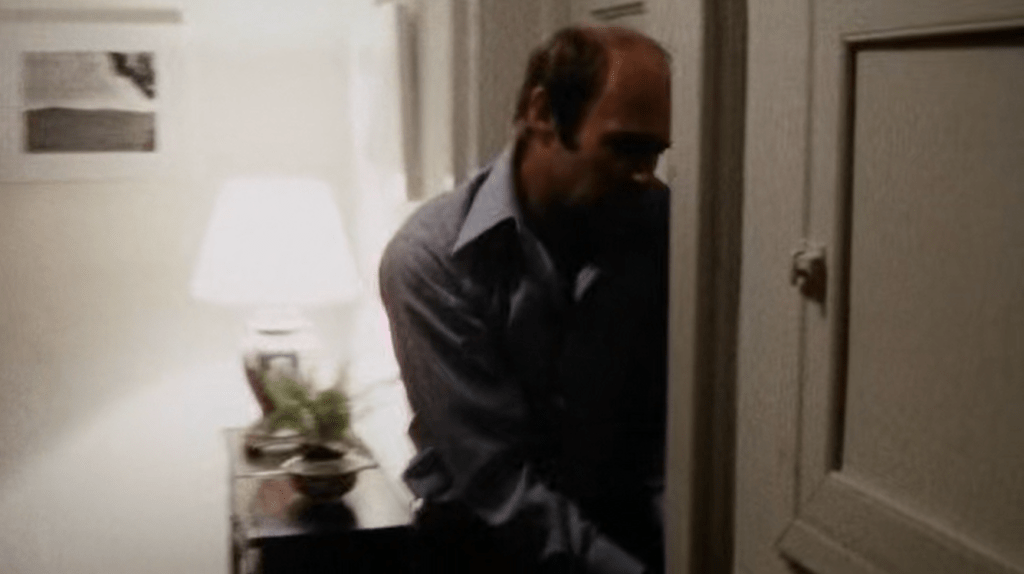

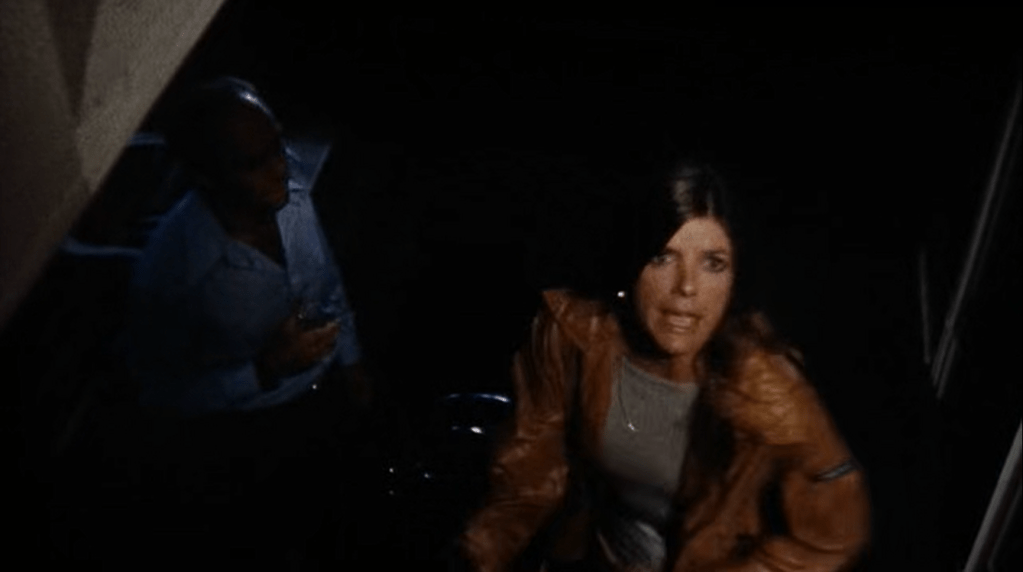

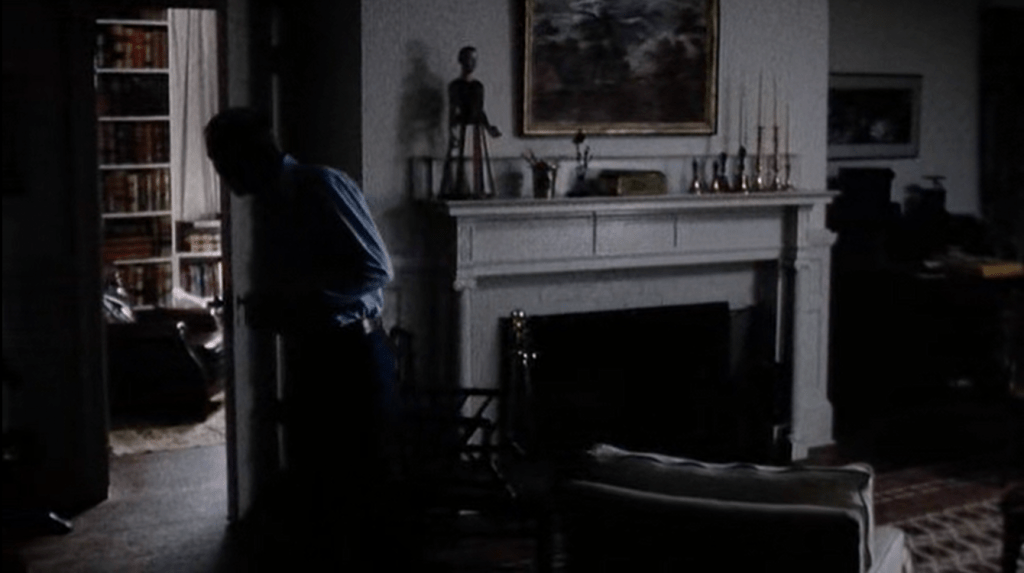

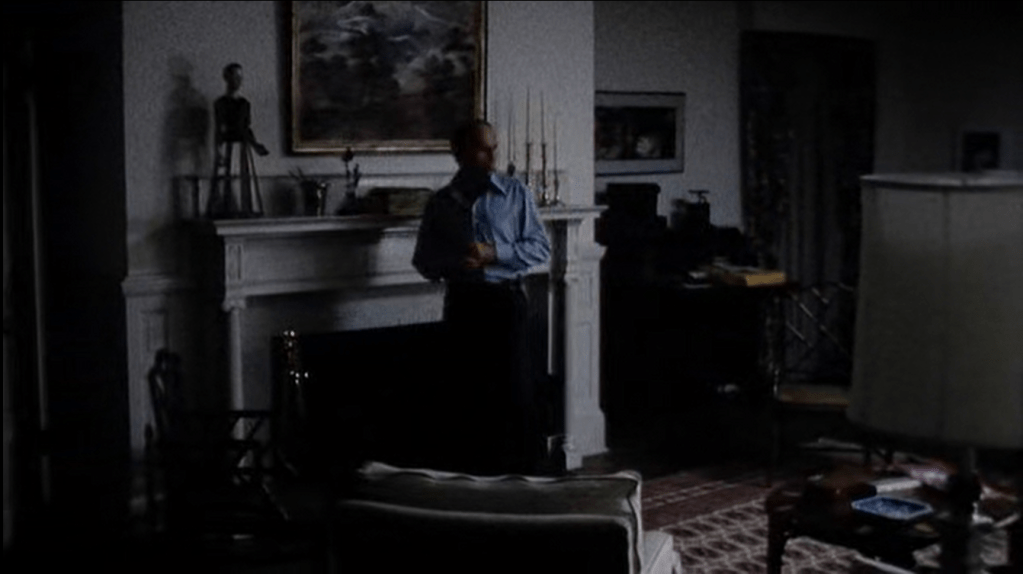

The multi-layered compaction and framing of Joanna’s body within the kitchen and the window frame makes her domestication consequential not only of the patriarchal ideology present in Stepford, but also by the architecture she occupies. Another scene in which Joanna’s imprisonment and exploitation as a housewife becomes architectural occurs when Joanna and Walter engage in a physical fight as she attempts to leave her domestic jail forever. Their tussle takes place on the main staircase of their home. The balustrade of the staircase in tandem with the upwards camera angle creates a foreboding image of a prison that Joanna is framed behind. Completely caged in visually and spatially, we understand that Joanna is being held against her will in her own home and will never escape so long as Walter is involved because “…Forbes therefore likens her escape from the house to a prison escape and Walter to her jailer.”[3]

Walter, throughout the film, acts as Joanna’s master, dictating every occurrence of her life in an attempt to tame her for his own benefit. He sees Joanna as an entity to be conquered, an object to make eternally beautiful, docile, and doting in service to him for his own personal gain. Walter ultimately succeeds, replacing an effervescent Joanna with a lifeless robot slave wife “Moreover, Joanna, through her death and replacement with a robot, will be “…no longer the biological offspring of a mother and father, but the product of a group of men… she represents all those women who are trapped by a feminine mystique that (in this case, literally) kills women.”[4] By imprisoning and replacing Joanna, he keeps her subdued and forces her into the robotic role of housewife expected of women at the time, he domesticates her.

The framing of Joanna’s body throughout the film represents her domestication as a product of both the patriarchal expectations of the Stepford community and the architecture she calls home. The metaphorical prison of life as a housewife becomes a spatial reality for Joanna in the ways the domestic spaces she occupies frame and constrict her body from escaping. The objectification, exploitation, and incarceration of Joanna’s body architecturally stems from the patriarchal ideology adopted in the suburban dystopia of Stepford; an ideology which disadvantages and oppresses women by perpetually bounding them to interior lives as unpaid domestic laborers rather than as independent, autonomous beings equal to their husbands.

[1] Miranda J. Brady, “‘I Think the Men Are Behind It’: Reproductive Labour and the Horror of Second Wave Feminism.” In Mother Trouble: Mediations of White Maternal Angst after Second Wave Feminism (University of Toronto Press, 2024), 33.

[2] Silvia Federici, “Wages against Housework,” 1974.

[3] Anna Krugovoy Silver, “The Cyborg Mystique: ‘The Stepford Wives’ and Second Wave Feminism,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 30, no. 1/2 (2002): 67, JSTOR.

[4] Krugovy, “The Cyborg Mystique,” 68.

sTILLS