Fargeat, Coralie, dir. “The Substance.” 2024.

FILM SUMMARY

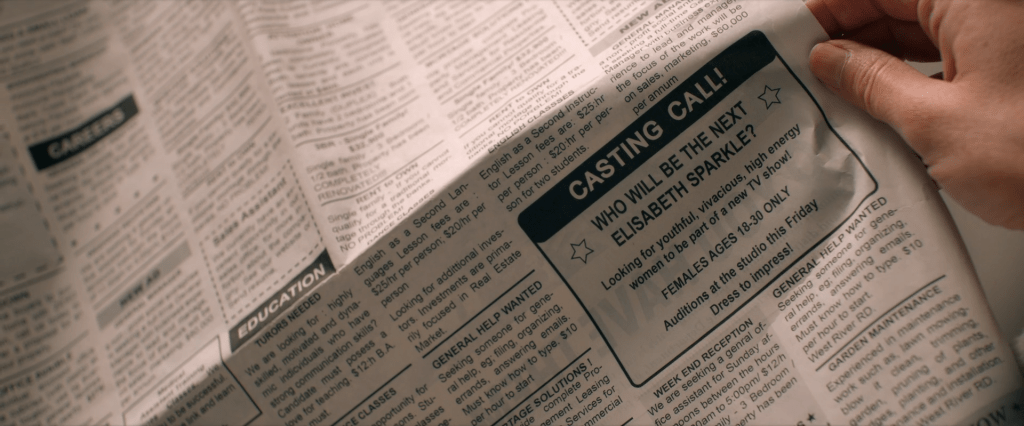

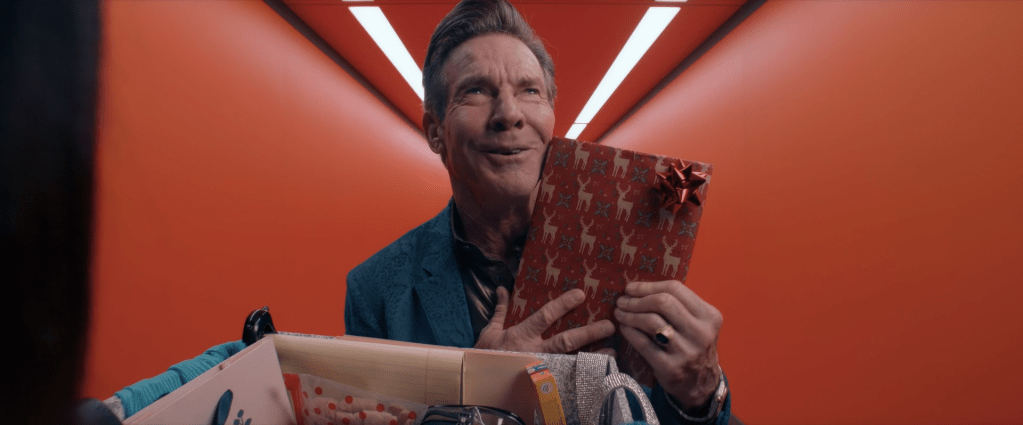

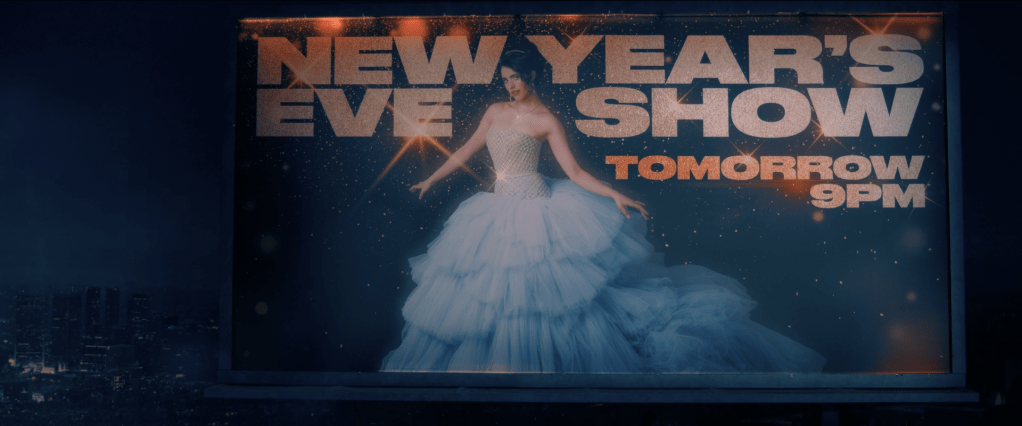

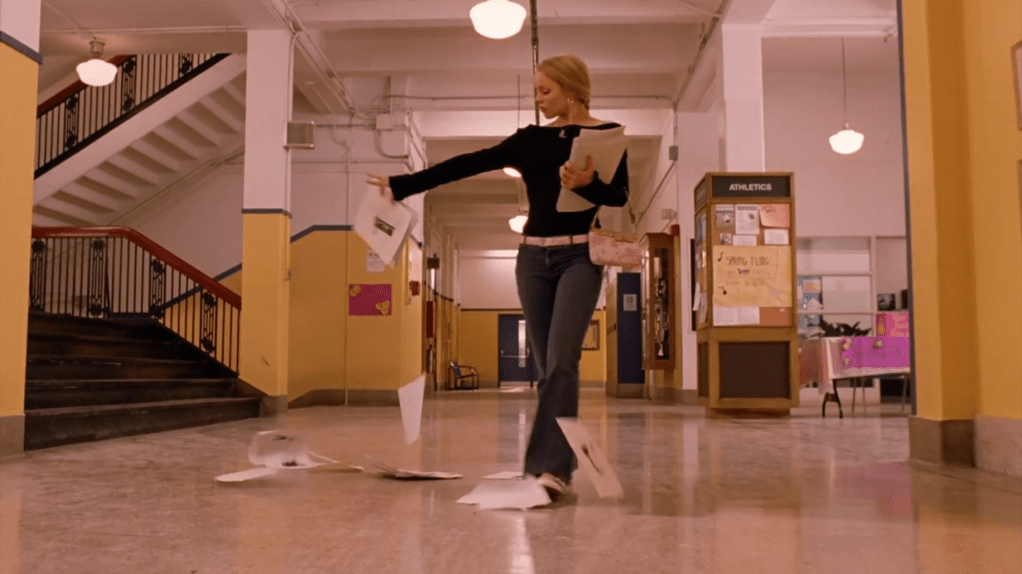

Elisabeth Sparkle is a former A-list, Academy Award winning actress living in Los Angeles. She has hosted Sparkle Your Life, a dance-aerobics exercise television program since the beginning of her career, but on her fiftieth birthday, she is unexpectedly ousted from her show. Harvey, the producer of the show, exclaims to someone over the phone that Elisabeth is ‘too old,’ a conversation that she accidentally overhears. Elisabeth, shattered and frenzied, crashes her car on her way home from the production studio, distracted by a billboard advertisement for her show already being taken down.

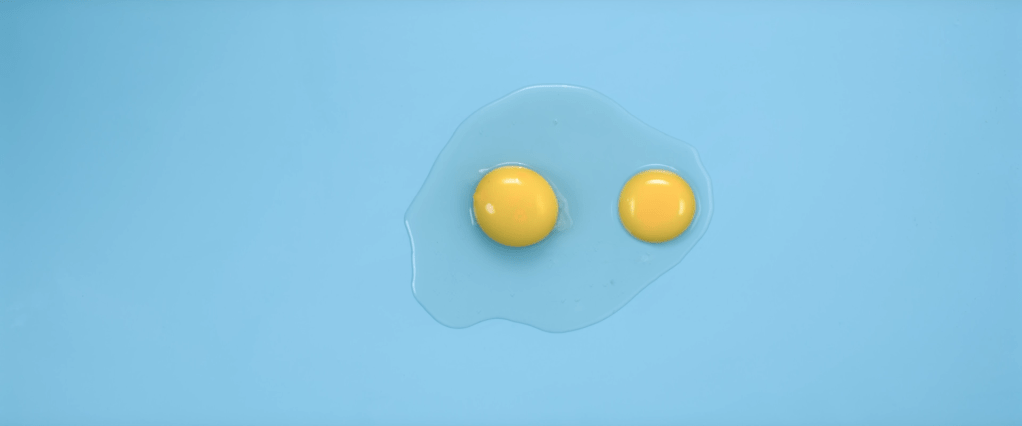

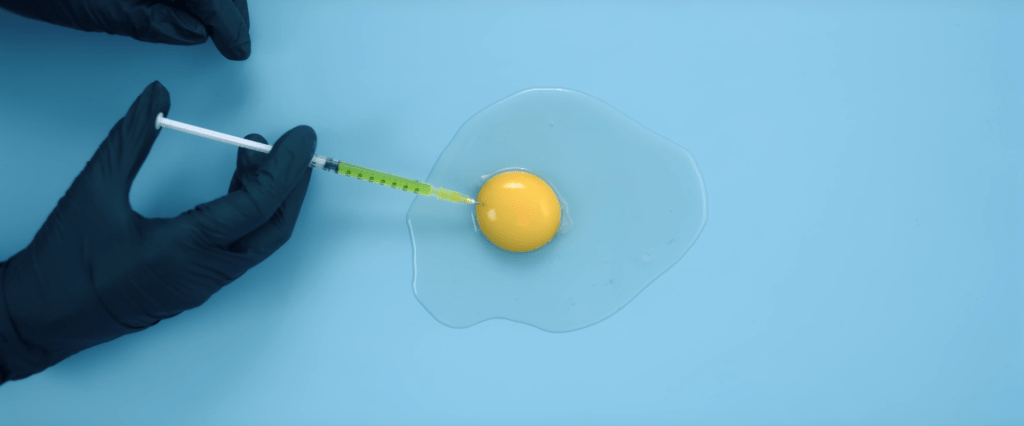

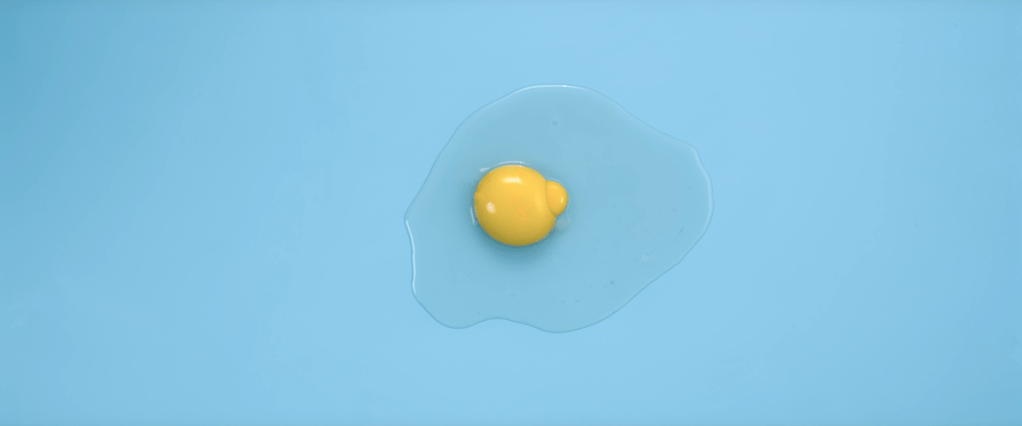

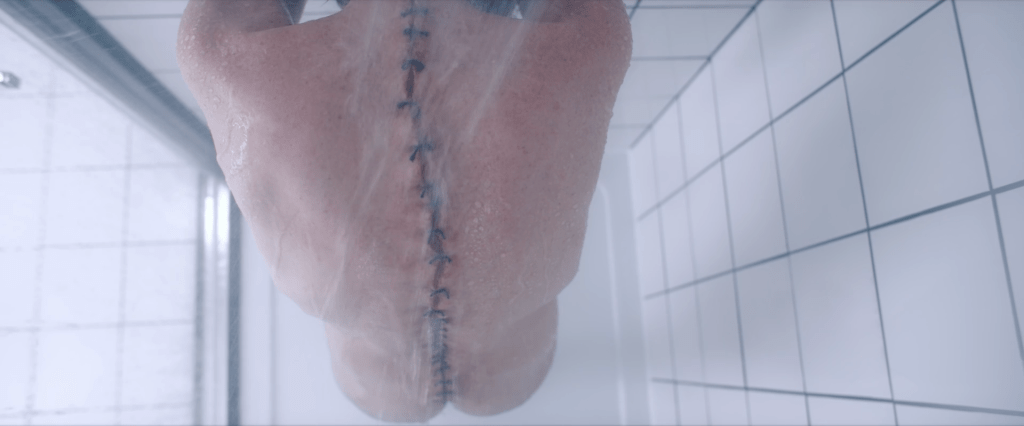

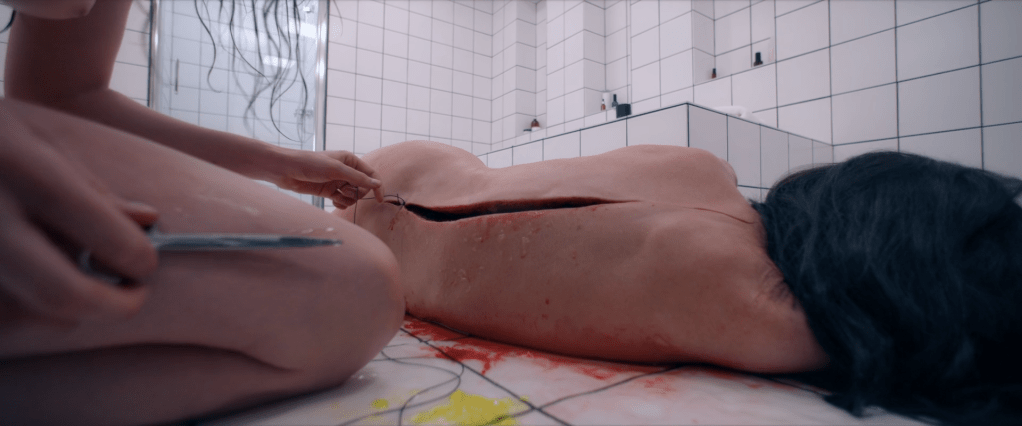

While at the hospital after the accident, Elisabeth is given a flash drive by a nurse with ‘THE SUBSTANCE’ written on it. At home, she watches the contents of the drive, learning about the black-market drug guaranteeing the creation of a “younger, more beautiful, more perfect” version of the user, the only caveat being that the two consciousnesses must switch every seven days, no exceptions, because in actuality they are two parts of one being. Elisabeth places an order for The Substance, despondent after the cancellation of her show and collects the first dose from a remote warehouse in the outskirts of Los Angeles. After injecting The Substance for the first time, a second, younger body crawls out of her spine. The younger being, Sue, connects Elisabeth to the IV drip food package provided in The Substance Starter Kit, stitches the gash in Elisabeth’s back, and extracts ‘stabilizer fluid’, injected into Sue daily to sustain her life, from Elisabeth’s spine.

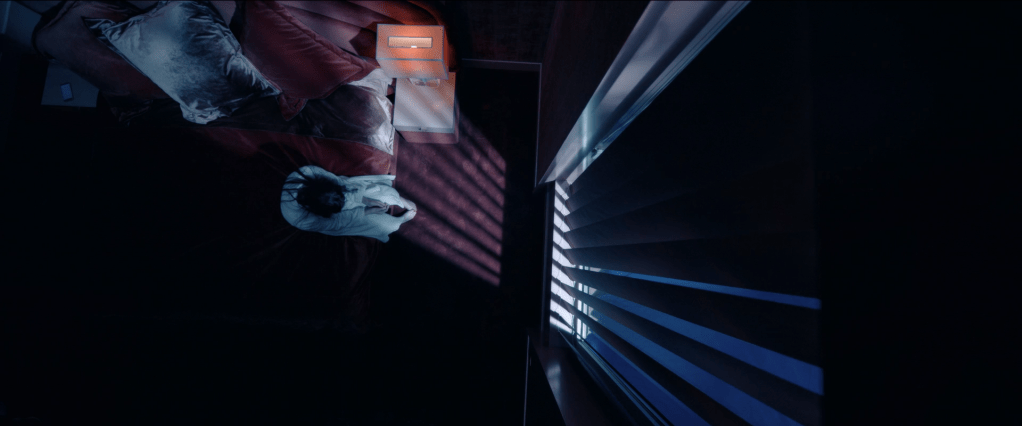

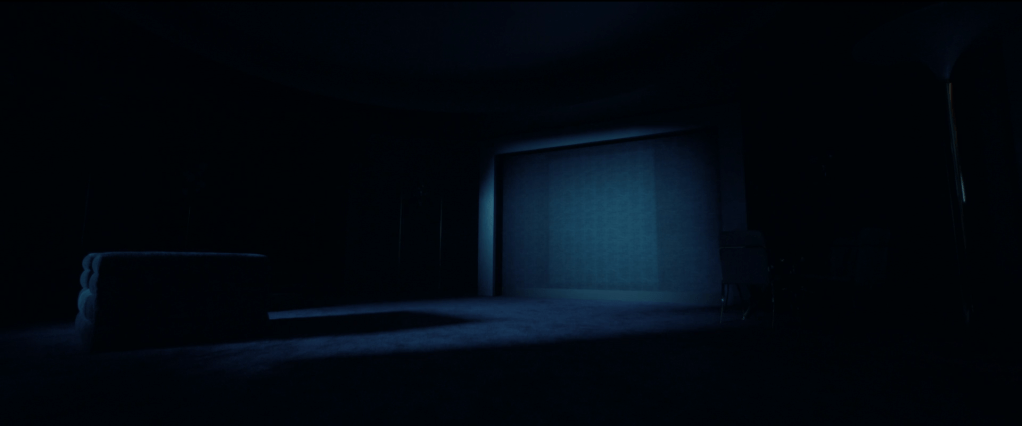

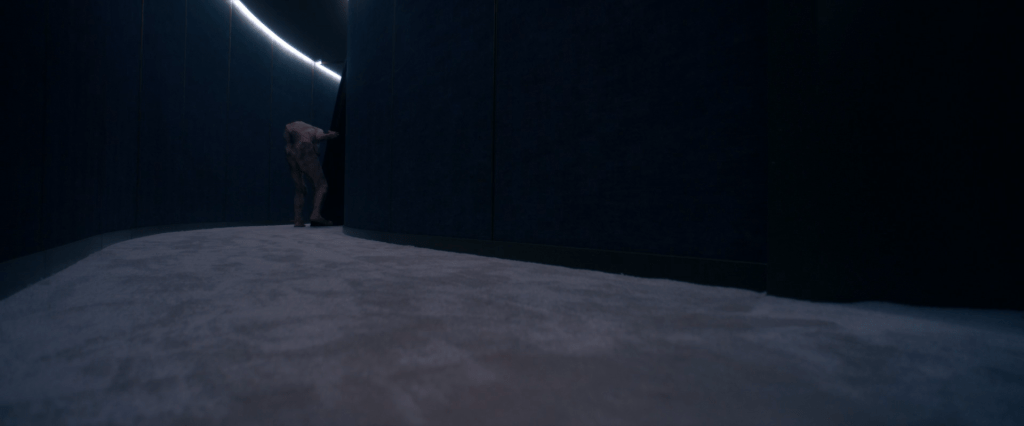

Sue auditions to replace Elisabeth on the aerobics show and receives the part, becoming an adored star overnight and eventually being offered the role of hosting the network’s New Year’s Eve Show by Harvey. During one of her weeks conscious, Sue discovers an empty space beyond the bathroom in her and Elisabeth’s apartment and transforms it into a secret self-imprisonment dungeon, dragging Elisabeth’s body into its darkness for storage during her cycle. Sue lives hedonistically during her weeks while Elisabeth slips deeper into isolation, reclusion, and self-hatred. Sue eventually abuses the stabilizer fluid, extracting more from Elisabeth’s spine to prolong her consciousness for a few more hours while she was hosting a man she hoped to have sex with.

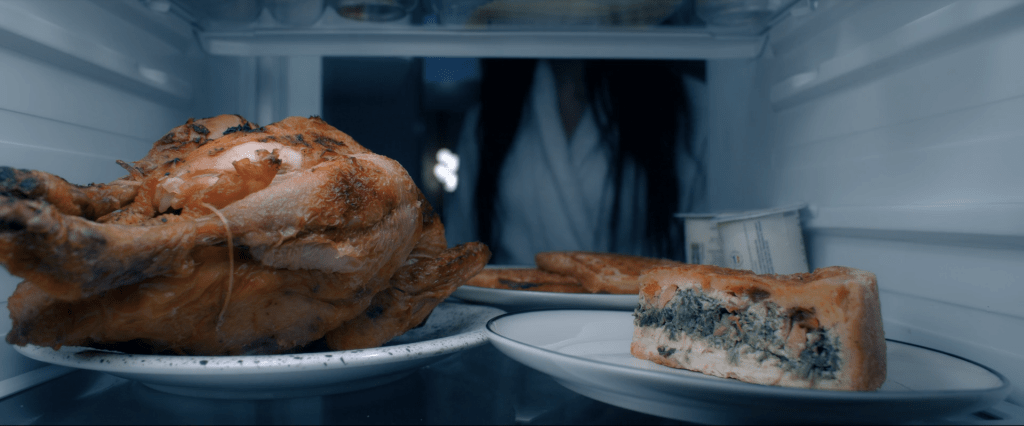

When Elisabeth regains consciousness after Sue’s stabilizer misuse, she discovers that her index finger has begun to age exponentially faster than the rest of her body. She contacts The Substance and they inform her that abuse of stabilizer by the younger self causes rapid, permanent aging in the ‘matrix’ the original body. The two consciousnesses develop feelings of hatred and bitterness towards each other as they continue to see each other as independent spirits. Elisabeth binge eats during her weeks ‘on’ which disgusts Sue while Elisabeth’s self-loathing grows because of Sue’s persistent abuse of stabilizer and disregard of their switching schedule. When Sue wakes up to the apartment in utter disarray, she decides to extract as much stabilizer from Elisabeth’s body as she can and refuses to switch again.

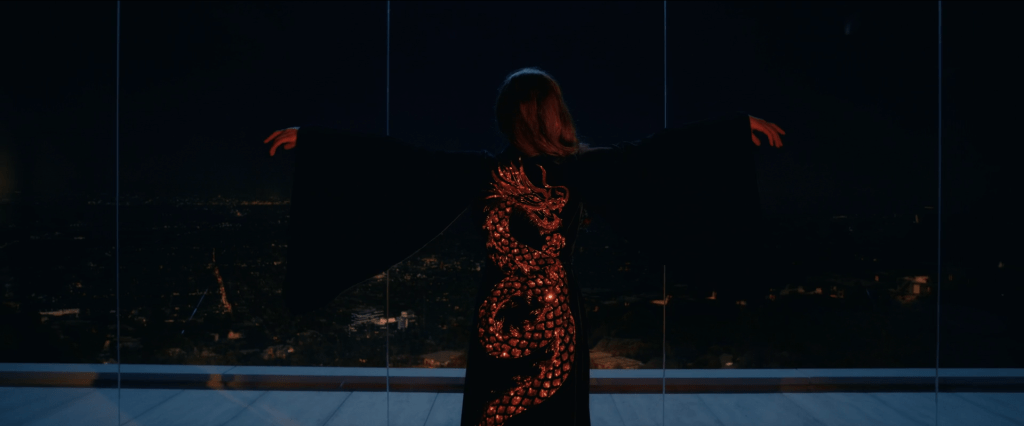

On the night before the New Year’s Eve Show, Sue discovers that she has run out of stabilizer fluid. Desperate, she calls The Substance; they inform her that she must switch with Elisabeth to regenerate the stabilizer fluid. Sue finally switches and when Elisabeth wakes up, she discovers that she has become her worst fear: a hairless, hunchbacked, elderly woman. Elisabeth elects to terminate Sue to avoid aging any further, but in the process of injecting Sue with the terminator fluid, realizes that she still desires the fame and adoration Sue was able to accrue by taking her former job. Elisabeth resuscitates Sue before delivering the whole vial of terminator fluid and once conscious, Sue realizes that Elisabeth had tried to kill her. The two consciousnesses fight, ending with Sue killing Elisabeth and departing to fulfill her duties as host of the New Year’s Show.

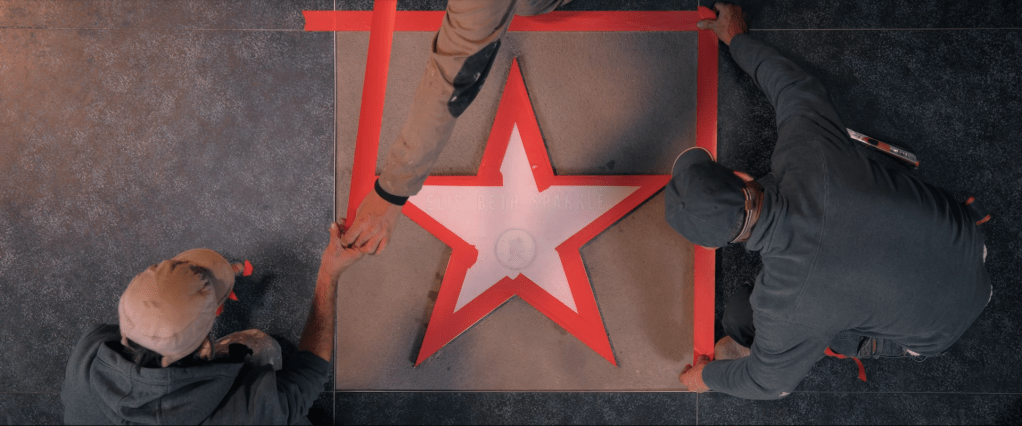

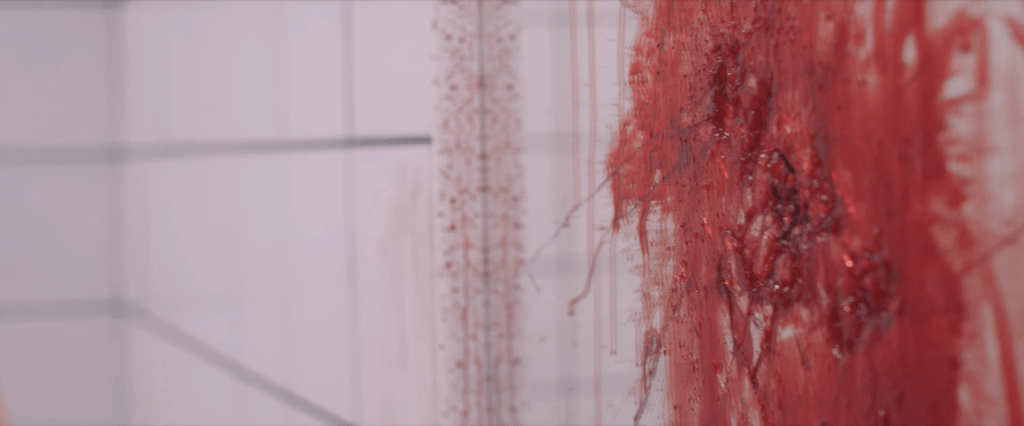

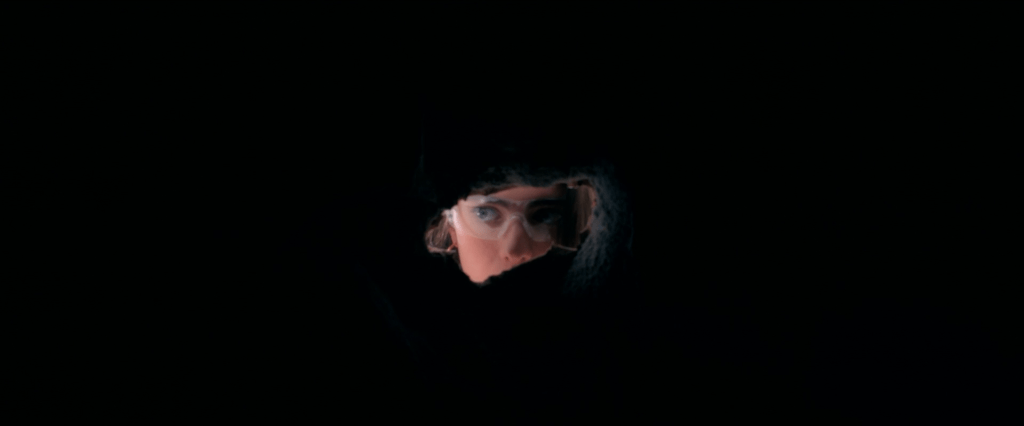

Sue begins to lose her teeth without any stabilizer left to inject and out of desperation, injects the rest of the original Substance fluid despite it being advertised as single use only to create a new version of herself for the show. A mutilated amalgamation of herself and Elisabeth emerges instead, named Monstro Elisasue. Monstro Elisasue dons a mask of Elisabeth’s face and returns to the production studio to host the New Year’s Show. The audience is frightened by the monster and decapitates her, but like a Greek Hydra, grows an even more grotesque head and floods the studio with blood from one of her broken arms. Elisasue runs from the studio and during her escape, implodes on herself, dispelling blood and organs. Elisabeth’s fifty-year-old face emerges from the wreckage and slithers to her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, smiling as she dissolves into a slimy puddle of blood, cleaned by a custodian the following morning.

Throughout The Substance, domestic architecture serializes the framing of Elisabeth Sparkle and Sue’s bodies, othering their bodies in space from every angle. The design of monotonous, uniformly flattening, compacting, and episodic frames produce readings of Elisabeth Sparkle and Sue as objectified, commodified, isolated, and contained bodies within their own home while also crafting a spatial language of representing the critique of patriarchal beauty standards and the treatment of the feminine body in media present in the film.

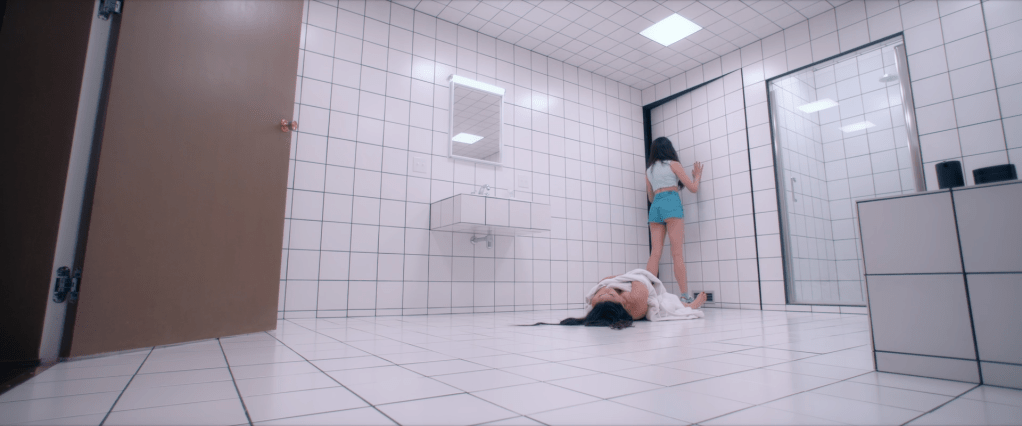

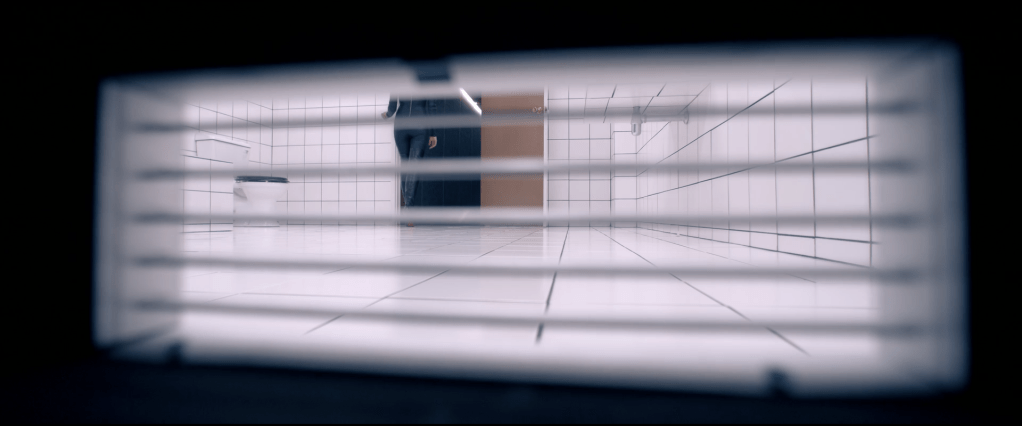

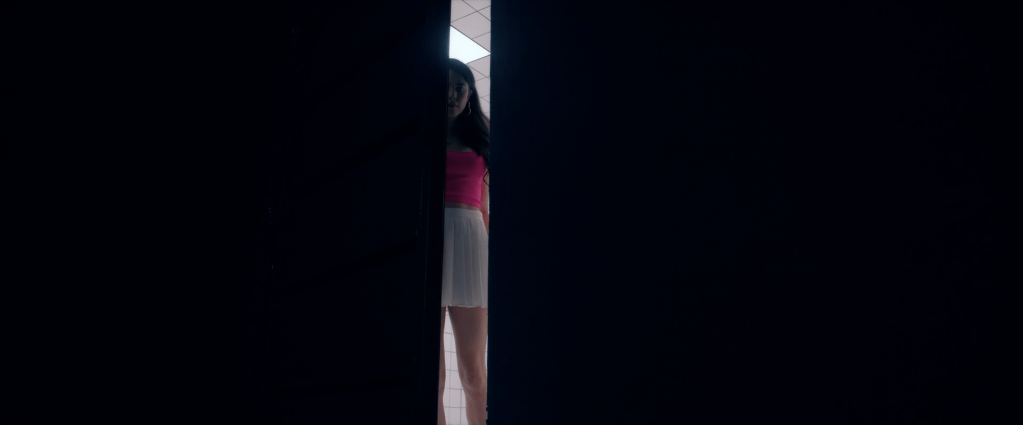

Elisabeth and Sue’s bathroom epitomizes the film’s critique of feminine self-loathing encouraged by a societal adoption of patriarchal misogyny in its design. The bathroom is sterile. Stark white, perfectly square tile covers every surface of the space. Aside from the living room, the bathroom is the largest space in the apartment, giving it hierarchical importance in Elisabeth and Sue’s lives. The bathroom in The Substance acts as Elisabeth and Sue’s personal lab, an uninviting environment in which they can endlessly dissect their appearance in the mirror against the neutralized white void that envelops them.

This monotony of the surface treatment in the bathroom already frames the women’s bodies within a non-descript vacuum of self-loathing, but the addition of a secondary frame—the mirror—adds to the framing of the feminine body within an exploitative lens. Through their scrutiny of their bodies in the mirror, Sue and Elisabeth reproduce the patriarchal equating of a woman’s beauty with her worth. John Berger in Ways of Seeing emphasizes that this behavior is engrained into the cultural feminine psyche:

She has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life. Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another.[1]

Elisabeth creates Sue because she has been told by both the men in her life and herself that her aging body no longer has societal worth because she no longer fits the youthful, Hollywood beauty standards for women.

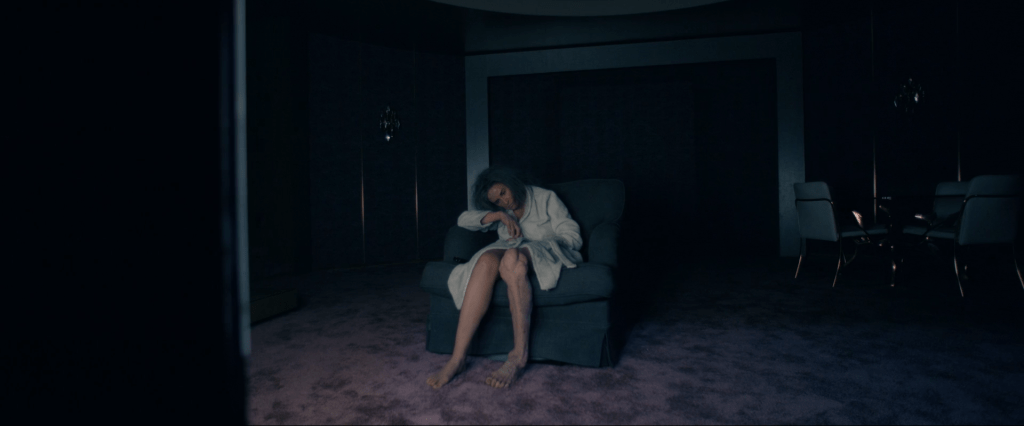

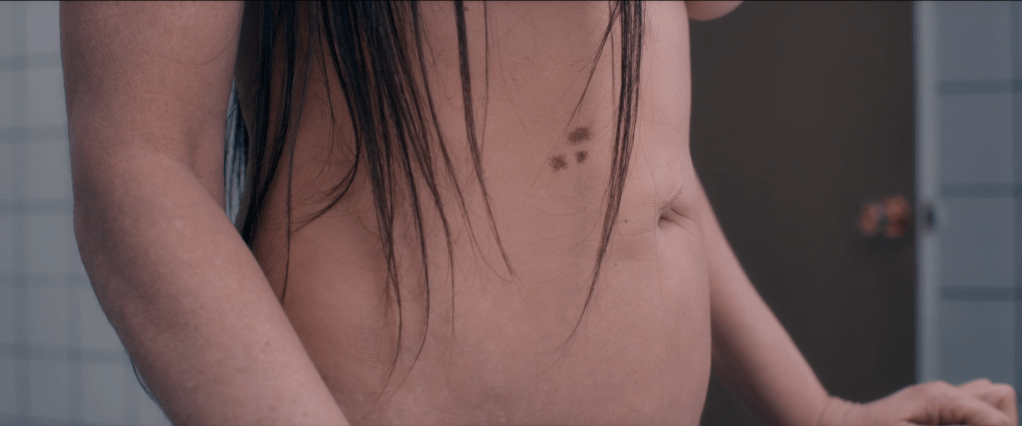

As they occupy the bathroom, Sue and Elisabeth are often naked, viewing and critiquing every inch of their bodies. Their vanity is destructive, leading themselves to self-imprisonment within their bathroom later in the film. The selected still in which Elisabeth analyzes her appearance in the bathroom mirror also references the fine art tradition of depicting Vanity as a naked feminine figure as a means of chastising women’s ‘self-absorption.’ Berger again describes this practice:

You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure. The real function of the mirror was otherwise. It was to make the woman connive in treating herself as, first and foremost, a sight.[2]

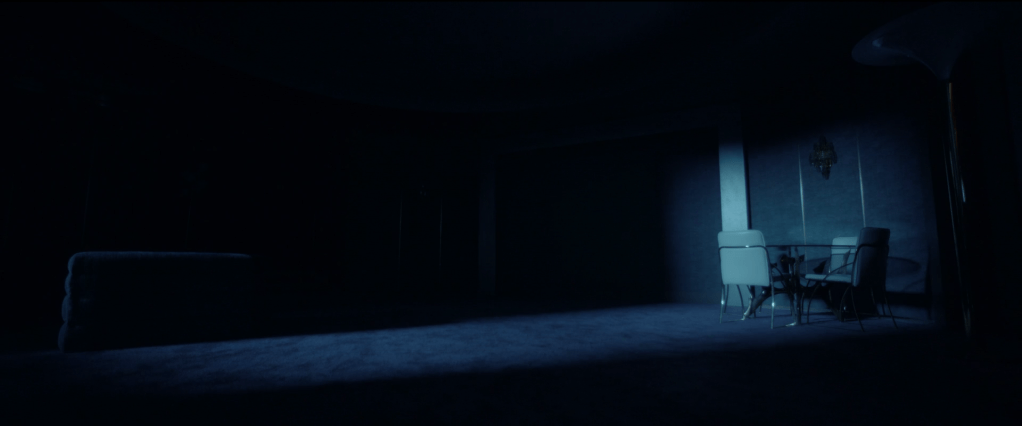

Elisabeth becomes Vanity, judging whether her body is sightly enough to the men who dictate her commercial success as a Hollywood actor. The framing of this particular still also places us as audience members in the role of the masculine voyeur. Elisabeth is not only frames within the view of the bathroom mirror, but also within the further compacted frame of the doorway into the space, juxtaposing the white, sterile bathroom with the darkness of the hallway where the camera is positioned. Elisabeth’s body is thus framed and objectified twice, once by herself in the mirror, and again by the camera and audience beyond the bathroom. Not only is Elisabeth practicing vanity through the personal, internal scrutiny of her own body, but we are the societal expectations depicting her body as nude object rather than as a naked human. She transforms her body into a nude image for herself through her dissection and unhappiness with her appearance, all done so through the architectural framing of her body as an object against a spatial void.

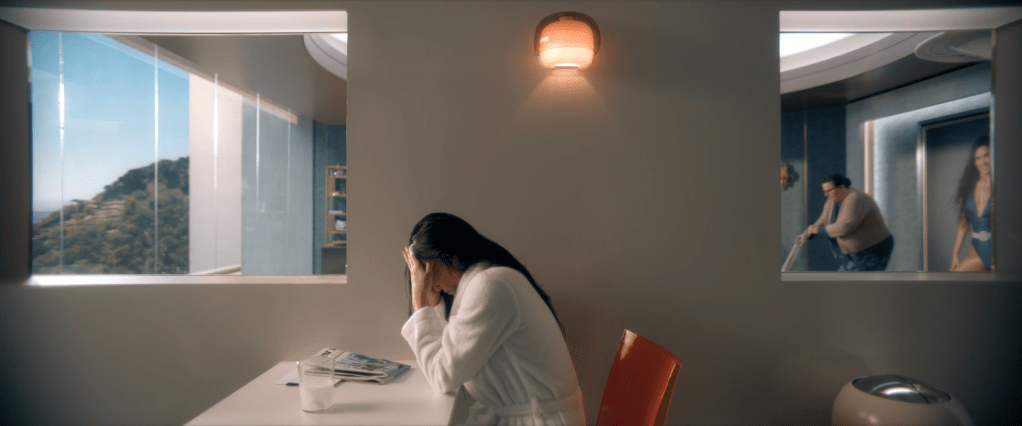

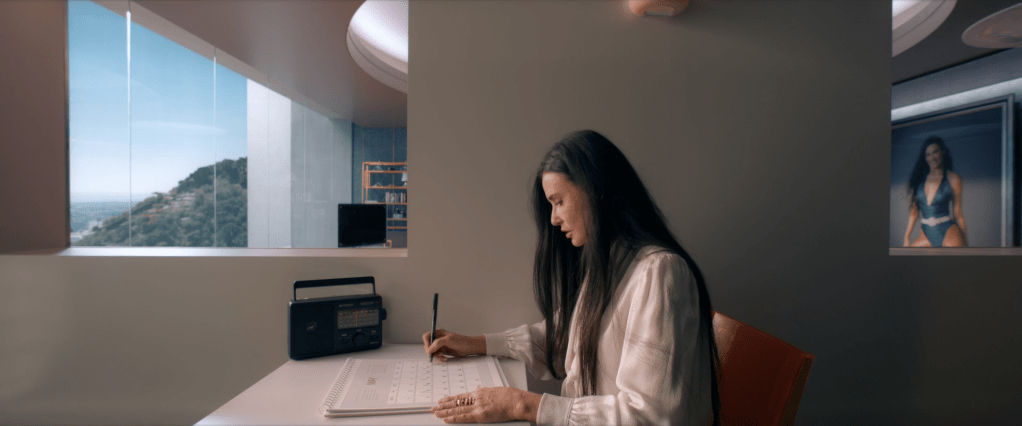

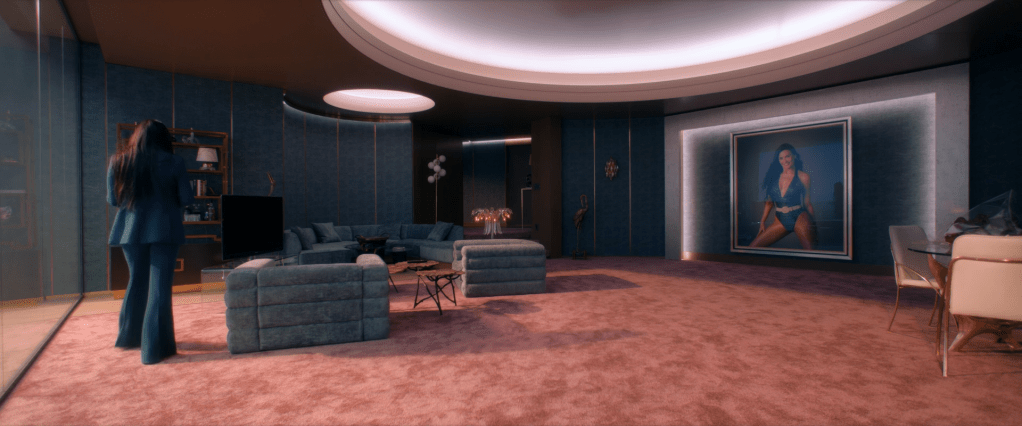

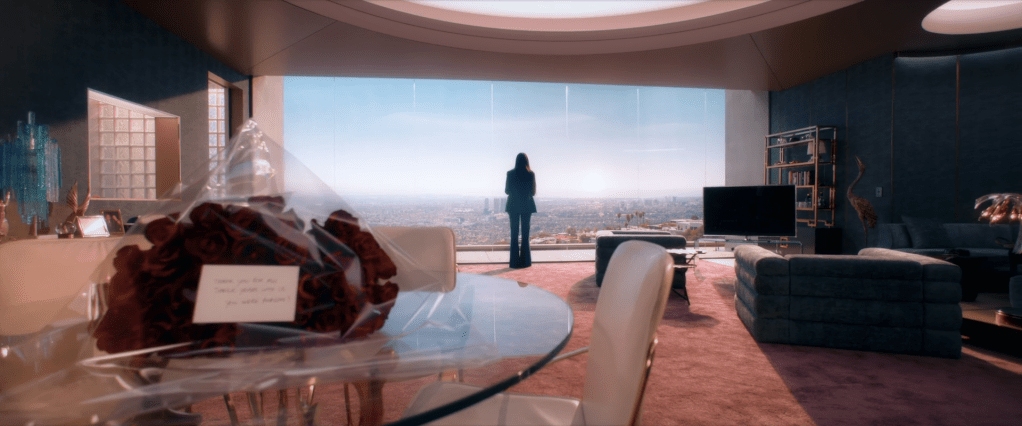

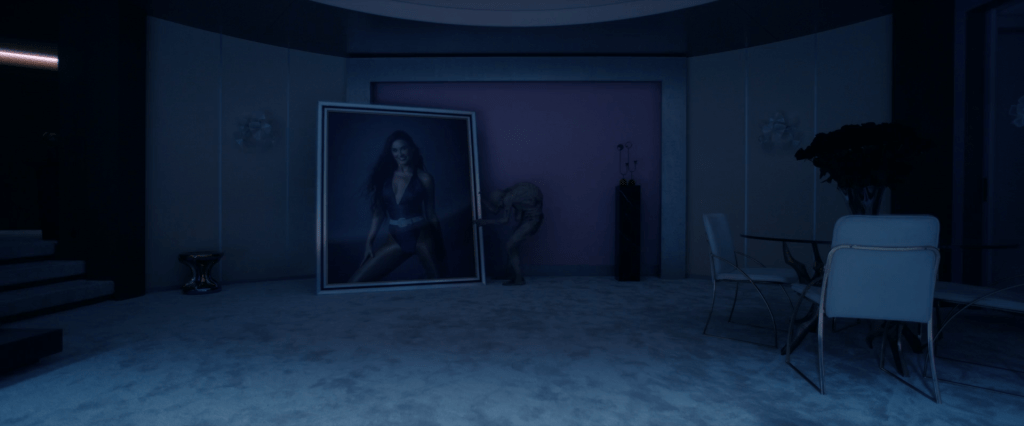

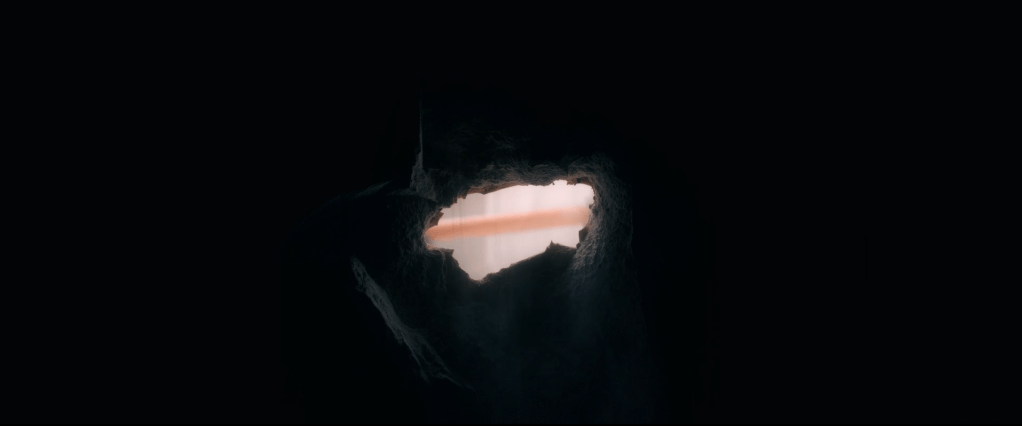

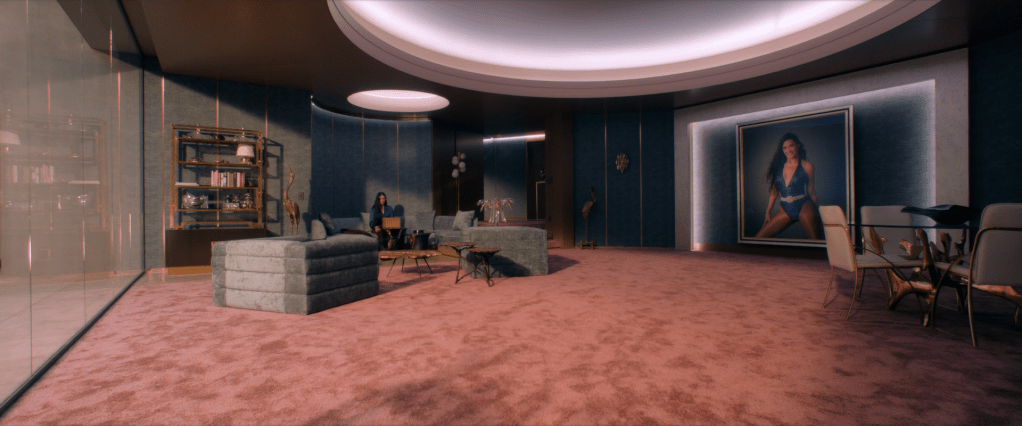

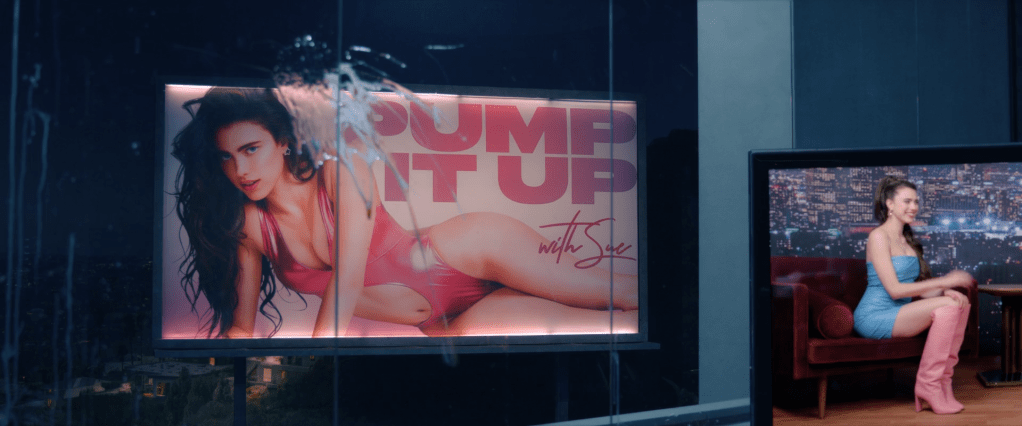

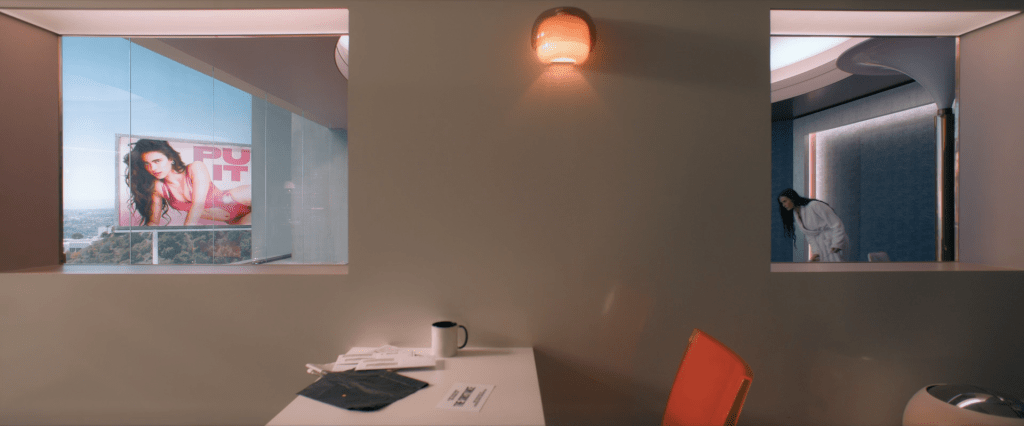

Elisabeth’s body is further objectified architecturally in a still capturing her as she sits at her kitchen table. The episodic, consecutive, serial framing of space and feminine bodies in this still represents the constant and multilayered framing and exploitation of Elisabeth and Sue by themselves, the Hollywood entertainment industry, and the patriarchal ideology that governs their careers and lives. Elizabeth is framed against the blank, white kitchen wall, then, a large photo of Elisabeth in her living room is seen through a puncture in the wall of the kitchen. In the photo, Elisabeth is wearing her costume for her recently cancelled exercise show Pump It Up, an outfit that further objectifies her body in its minimal covering of her body. Framed through a second puncture in the kitchen wall and the large, 16:9 cinematic window in the living room is a billboard advertising Sue’s new show, Sparkle Your Life, Elisabeth’s replacement.

Both Elisabeth and Sue have been exploited as objects and commodities by the Hollywood entertainment system. They have been used as a means of visual pleasure to broad audiences and economic gain for the men presiding over their commercial success, but are easily replaced by an even younger, more attractive, more ‘worthy’ woman as soon as they cease to bring success to their male Hollywood overlords. They can’t escape the result of their commodification. It follows them home and is visible from every corner of their apartment. The billboard ad and poster are quasi-mirrors, taunting Elisabeth with the beauty she ‘once had’ and the success Sue has achieved, leaving her worthless in the eyes of the men once in charge of her career. This enveloping by images of Elisabeth’s own body again connects to the writing of John Berger:

Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.[3]

Elisabeth is surrounded by objectified and exploited images of her own body and her ‘more valuable’ replacement, Sue. The architecture of her apartment exacerbates the self-loathing she feels by framing her body as an image to be surveyed by the societal misogynist engrained within her psyche by the men presiding over her life.

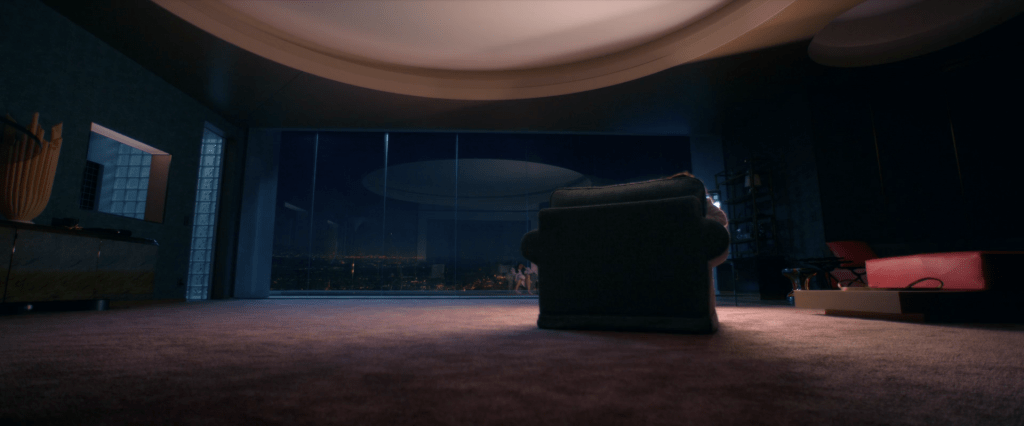

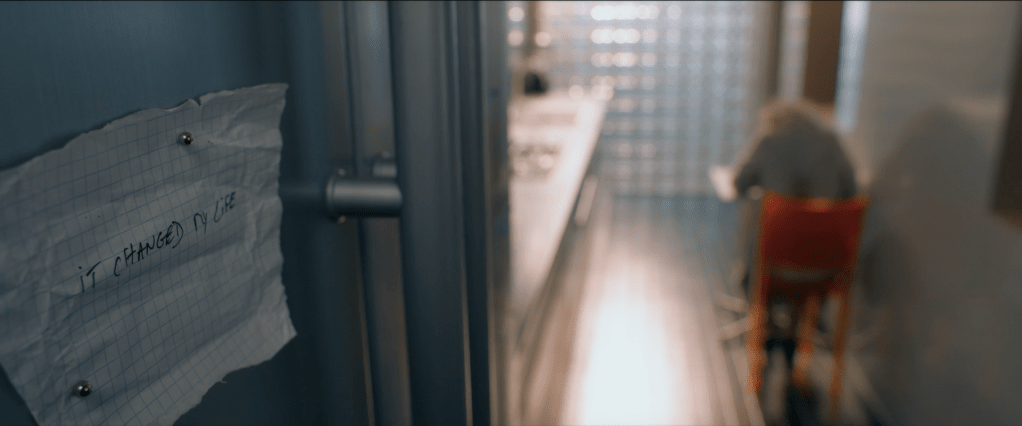

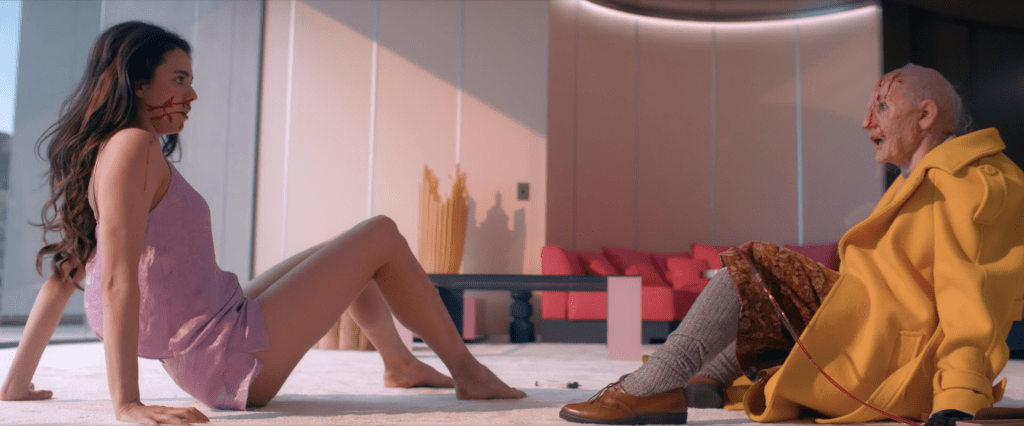

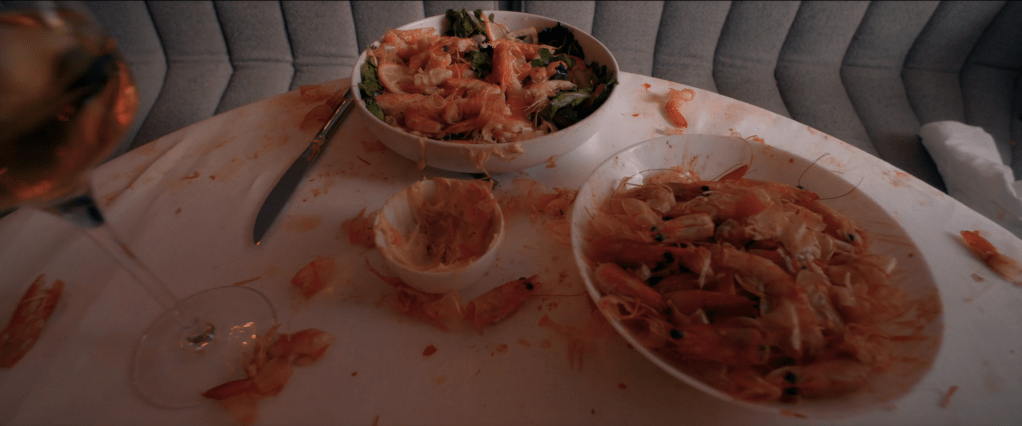

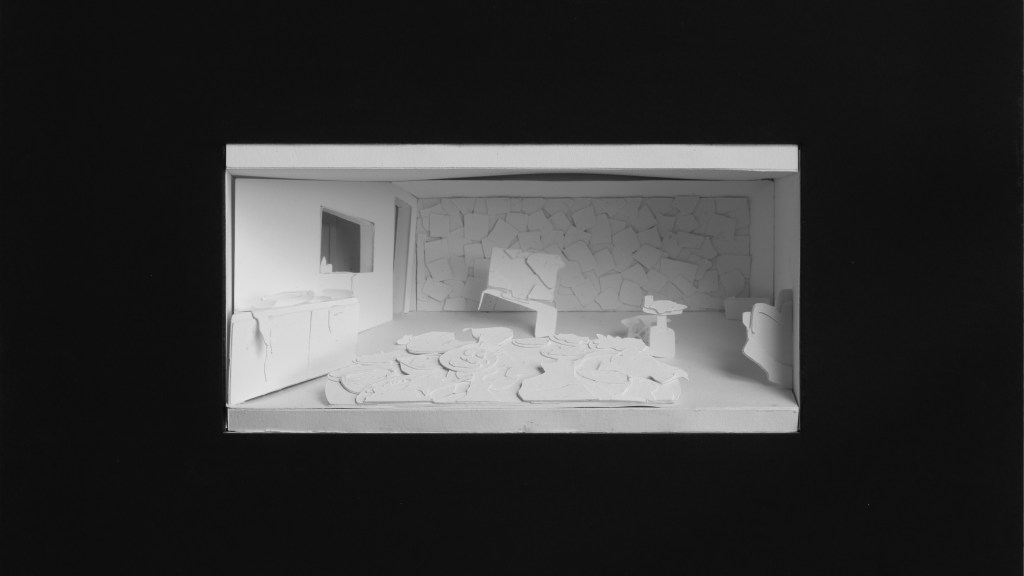

The psychological impact of Elisabeth and Sue’s diffidence is most dramatic in the final selected still from The Substance. Sue finds herself surrounded by a mess of Elisabeth’s gluttony resulting from her declining mental state. Plates of half-eaten food litter the living room and Elisabeth has fully blocked out the window in the space with yellowing newspaper. The uniformity of the disorder around Sue frames her body within a void, similar to the strategy implemented in the design of the bathroom in their apartment. Elisabeth’s sense of worthlessness has become all-encompassing at this point and Sue is flanked on all sides by its spatial manifestation. Sue herself is disgusted by Elisabeth’s littering of their home, mirroring Elisabeth’s own feelings about herself and her aging body. The misogynistic standards she has been held to for her entire career have thrust Elisabeth into a deep depression. She self-sabotages, she imprisons herself, she no longer cares for her body and its health because she, like the men in her life, view it as worthless now that she is older. Elisabeth’s madness effectively domesticates her, entrapping her within a space with no external contact. When writing about The Stepford Wives, but still applicable to The Substance, Samantha Lindop describes the historical origins of restraining mental anguish to the domestic realm:

Instead of confinement and brutality, behaviour was organised around surveillance and judgement, guilt and self-consciousness. As long as inmates restrained themselves, were agreeable, and did not break the rules (things that all require awareness about one own madness) they would not be subject to constraint.[4]

Elisabeth practices self-restraint, reinforced by her consciousness of the misogynistic beauty standards she is constantly held to by herself and the Production Company she used to work for. Throughout the film, Elisabeth and Sue represent both surveyor and surveyed woman, the two parts of this psyche molder by patriarchy, both repressed and constrained by the societal expectations of themselves as women and spatially restricted in their domestic space through the way it objectifies their bodies.

[1] Berger, “Chapter 3.”

[2] Berger, “Chapter 3.”

[3] Berger, “Chapter 3.”

[4] Samantha Lindop, “The Stepford Wives and Liberal Feminism.” In The Stepford Wives, (Liverpool University Press, 2022), 78.

STILLS